Wojciech Kossak: Memoirs, 1913

The chapter on "Zakopane" (p. 131-150), depicting Kossak's first stays in his holiday resort between 1880 and 1935, describes the place and the High Tatras as a pristine world around 1880. It had never really been occupied by the partitioning powers of Russia and Austria and, apart from a few writers and painters, had also been unknown to many Poles. Kossak tells of an unspoilt, rugged mountain world that could only be explored by local guides, with a population that persisted in ancient traditions, and few holidaymakers, some of whom had travelled from far away. His detailed description of his mountain hikes explains the fascination of numerous Polish painters[17] for the Tatra landscape and the culture of the native population of the Gorals. Kossak himself was obviously only sporadically interested in these motifs in his painting.[18] In 1886 Zakopane was granted the status of a health resort, and hotels and boarding houses were built. In 1899 the town was connected to the railway.

Back in Berlin, Kossak was invited by the Emperor to attend the annual recruits' swearing-in ceremony of the guards regiments in autumn. He took part in the ceremony wearing an Austrian Ulan uniform, as he would in future do at all official occasions and receptions. As in the years that followed, as a member of the Austrian legation he attended the annual reception in the city palace, the "Schleppcour", at which all high-ranking personalities had to present themselves to the imperial couple individually, (p. 153-160).

The following chapter, "The Return of the Imperial Couple from Palestine" (p. 163-170), follows Kossak's acquisition of the studio in Monbijou Castle in 1898. From October to November of that year, William II and his wife had travelled to Palestine, part of the Ottoman Empire, consecrated the German Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem and visited the cities of Haifa, Jaffa, Beirut and Istanbul. Immediately after the reception of the imperial couple at the Brandenburg Gate and still in gala uniform, Wilhelm II visited Kossak, who had been looking forward to the reunion with his "sublime and powerful patron", in his studio: "This was a proof of great benevolence and sympathy, since several other painters and sculptors were working on imperial commissions in Berlin at the same time as I was: Begas, Rocholl, Röchling, Koner, Walter Schott etc." (p. 163-165) The Emperor gave Kossak a detailed account of his experiences in the Orient.

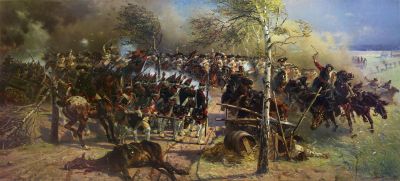

The painting "The Battle of Zorndorf" was not yet finished in the spring of 1899 because Kossak's father's illness and death had prevented its completion. Thereupon, Wilhelm made a personal appeal to Anton von Werner (1843-1915), chairman of the jury of the Great Berlin Art Exhibition and director of the Royal Academy of Arts, to ensure that the monumental painting could nonetheless be submitted to the exhibition later (p. 168-170); it was then exhibited there from May to September that year.[19]

Around 1900 the first problems for Kossak's stay in Berlin became apparent. The increasing phenomenon of "Hakatism",[20] synonymous with a growing hostility towards Poland in Prussia, and the criminal trial against Polish citizens after the school strike in Wreschen, made it impossible for Kossak to continue his stay in the Prussian capital. Despite his overtly Polish nationality and his Austrian uniform, he had never experienced any problems in Berlin, but "every trip to Poznan", he writes in the section entitled "Wreschen" (p. 170-172), "led him into an atmosphere of growing conflicts and national agitation". Kossak took the constructional changes in Monbijou Castle and the necessary abandonment of the studio as an opportunity to ask the Imperial Chancellery to allow him to complete the outstanding paintings in his studio in Krakow. However, the commander of the imperial headquarters, Hans von Plessen (1841-1929), saw through the pretext and rejected the request in the following words: "In any event, as a Pole, you should remain at your post more than ever. You can serve your compatriots much better here than if you were to leave."

[17] Kossak names (p. 132) his father, Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899), Wojciech Gerson (1831-1901) and Leon Dembowski (1823-1904). Furthermore, other painters including Kazimierz Alchimowicz (1840-1916), Walery Eljasz-Radzikowski (1841-1905), Stanisław Janowski (1866-1942), Damazy Kotowski (1861-1943), Aleksander Kotsis (1836-1877), Ludwik de Laveaux (1868-1894), Władysław Aleksander Malecki (1836-1900), Julian Maszyński (1847-1901), Aleksander Mroczkowski (1850-1927), Antoni Piotrowski (1853-1924) and Stanisław Radziejowski (1863-1950) were busy working on landscape and genre motifs from the Tatra (all biographies in the Encyklopaedia Polonica on this portal).

[18] Only two paintings by Kossak on themes of the High Tatra are known from exhibition catalogues: “Z Zakopanego/Aus Zakopane“ (1881) and “Pieśń o zbóju Janosiku/Lied über den Räuber Janosik“ (1883). In addition, he apparently painted motifs from the Podhale and the Tatra during the interwar period; cf. https://z-ne.pl/t,haslo,2443,kossak_wojciech.html. In 1914 Kossak bought a wooden house in Zakopane, ul. Kościuszki 20. It still exists today.

[19] The Great Berlin Art Exhibition. Catalogue, 7. May to 17. September 1899, Berlin 1899, page 34 (Digitalised at: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/gbk1899/0049/image)

[20] The term "Hakatism", used mainly by Poles, referred to the activities of the nationalist " Deutsche Ostmarkenverein", founded in Poznan in 1894. It had been formed from the initials H, K, T, of the founders of the association, Hansemann, Kennemann and von Tiedemann. It subsequently also referred to the anti-Polish policy of the Prussian authorities.