Stanislaus Kostka in Recklinghausen-Suderwich. The portrayal of a Polish national saint in a stained-glass window in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church

Mediathek Sorted

Recklinghausen

The town of Recklinghausen was the main centre of the “Vest” of the same name. It had belonged to the territory governed by the archbishops of Cologne since the High Middle Ages. As a result, the population remained Catholic during the Reformation period. In 1815, the Congress of Vienna assigned the region to the Kingdom of Prussia, which was mainly Protestant. This led, among other things, to an influx of evangelical leaders and administrative officials. The beginning of the coal mining era saw a marked increase in the number of evangelical immigrants. Here, too, the Prussian “culture battle” led to considerable tensions between Protestants and Catholics in the wake of the founding of the German Empire in 1871. When the priest in Suderwich died in 1879, for example, several years passed before the Prussian government gave permission for a new occupant to fill the post. In this village, which was later incorporated into the town of Recklinghausen, this discrimination would not be forgotten for decades afterwards.

In 1856/57, the first pit fields for the Henriettenglück I/II/III coal mines to the south-east of the town were awarded to their new owners. In 1872, following the foundation of the Empire, they were renamed “King Ludwig I/II/III”. Ludwig II, the Bavarian monarch, remains popular today as the romantic “fairytale king” with his sumptuous palaces in Neuschwanstein, Herrenchiemsee and Linderhof. In Recklinghausen, the name was chosen as a reminder of the proclamation of the Prussian king Wilhelm I as German Kaiser, which had been initiated by a “Kaiserbrief”, an imperial letter written by Otto von Bismarck and signed by Ludwig II. The name of this coal mine therefore served as a symbol of patriotic Protestantism [ ].

The King Ludwig I/II/III coal mine began operations in 1885. At the turn of the century, more than half of the mine’s employees spoke Polish. In 1902, the Ludwig IV/V mine was opened six kilometres away. Its shafts had been sunk on the outskirts of Suderwich. In the bitterly cold post-war winter of 1946/47, this mine unexpectedly gained cultural importance as the supplier of “illegal” Ruhr coal to the Deutsches Schauspielhaus theatre in Hamburg. The theatre management demonstrated its gratitude by putting on guest performances in Recklinghausen. This marked the beginning of the world-famous “Ruhrfestspiele” theatre festival. The first performances were given in the Saalbau hall in Recklinghausen; later, a proper festival theatre was built in the town. The Hamburg State Opera also organised “Invalidenkonzerte” concerts in the Lohnhalle hall, where wages were once paid out, of the King Ludwig I/II/III mine as an expression of their special relationship with the miners [ , , , , , ].

The St.-Johannes-Kirche church in Suderwich

Suderwich already had its own church from around 1250, a small wooden building dedicated to St. John (St. Johannes) the Baptist. After being destroyed by fire, it was replaced in 1441 by a sandstone structure. A new bell tower was built in 1626, and a new aisle in 1821/22.

A handful of miners who worked at the collieries in the neighbouring towns had also been living in Suderwich since the 1870s. When at the end of the 19th century it became clear that the King Ludwig IV/V mine would go into operation, the influx of miners very quickly became a flood. Between 1900 and 1914 alone, the population of the village increased from 1,448 to 6,953. Already by 1899, the small village church was no longer able to house the large congregation, and the parish decided to build a larger one. The new church was designed by the architect Franz Lohmann, who also created the designs for four other churches in what is now part of the Recklinghausen municipal area [ , , , ].

“Suderwich Cathedral”, a spacious hall church with a 75-metre-high tower, was consecrated on 20 October 1904. The interior space was fitted with high-quality fixtures, most of which remain intact today: three neo-Gothic carved altars, four confessional booths and a large number of church benches. All the stained-glass windows have also remained intact – a real rarity in the Ruhr region. The church therefore remains a source of fascination as a work of sacred art overall. It is also an impressive reminder of the mining and cultural history in the Vest Ruhr mining region [ ].

In Suderwich, too, a large number of the immigrants were not of German nationality, but came from the Czech speaking regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and above all – with Polish as their native language – from the eastern Prussian provinces. From the early years of the 20th century onwards, services in the Catholic parish were therefore also held in Polish and Czech. In 1904, a padre from the Franciscan monastery in Dortmund visited Suderwich for individual appointments. Later, two Westphalian chaplains were stationed here, who had previously learned the languages spoken by the congregation: Heinrich Theißelmann (1905–1907) and Robert Zumloh (1910–1914).

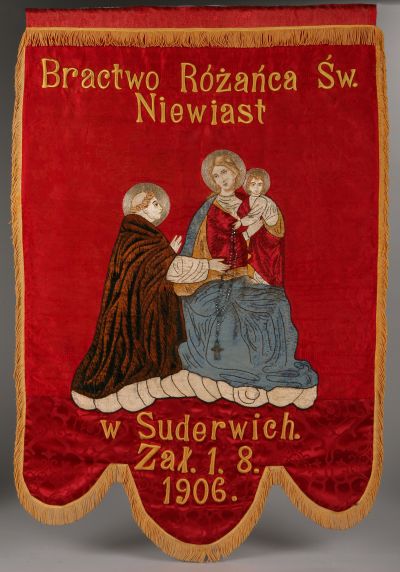

The different nationalities were also reflected in the church societies that were established in Suderwich. For example, there are records of a St. Wenceslas society (for the Czechs) and a St. Stanislaus society (for the Poles). In 1909, Polish miners also founded a “St. Joseph workers’ association” (Arbeiterverein St. Josef). They did so in response to the refusal by the local “St. Barbara miners’ association” (Knappenverein Sankt Barbara), which had been founded in 1881, to accept immigrant workers as members. Apparently, the status-conscious German miners were unwilling to mingle with their Polish colleagues. During that time, St. Joseph was also the patron saint of a Ruhr Pole “Brotherhood of St. Rosary of the women in Suderwich”, of which a pennant labelled in Polish remains [ ]. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, there is also a window depicting Saint Stanislaus Kostka in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church, which was produced following the influx of Ruhr Polish Catholics to Suderwich [ ].