Stanislaus Kostka in Recklinghausen-Suderwich. The portrayal of a Polish national saint in a stained-glass window in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church

Mediathek Sorted

Ruhr Poles

From the final third of the 19th century onwards, the advancing industrialisation of coal mining and steel production led to an enormous demand for labour. From 1890 to 1914 in particular, countless people from near and far moved to the Rhenish-Westphalian mining region between the Ruhr and Lippe rivers. Nearly half a million of them came from the eastern Prussian provinces of Silesia, Posen and West and East Prussia, and had grown up speaking Polish as their native language. Aside from the Protestants from the Masuria region in East Prussia, most of these migrants were Catholics.

The majority of the immigrants headed for the newly developed coalfields in the northern Ruhr region. In 1890, around 5% of the population of the town of Recklinghausen were of Polish nationality; 20 years later, this figure had already grown to 23%. In the surrounding district, the Polish share of the population grew from 5.8% to 15.7% during the same period. In total, more than 53,000 people with Polish as their mother tongue lived in the town and district of Recklinghausen in 1910, constituting more than 10% of the Poles living in the Ruhr region overall.

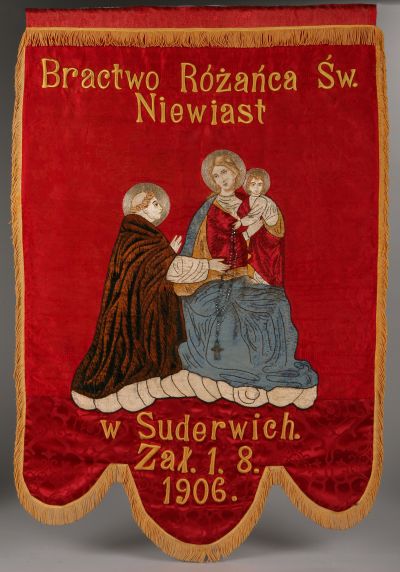

These “Ruhr Polish” immigrants brought their own religious customs with them to their new homeland. Among the Catholics, this included the national Polish cult surrounding the Madonna of Częstochowa and the veneration of certain saints, such as Hedwig (Jadwiga), Adalbert (Wojciech), Kasimir (Kazimierz), Michael (Michał Archanioł) and Stanislaus (Stanisław) Kostka. Special societies of worship were founded and reverence for the saints was expressed artistically in the form of altarpieces, sculptures or stained-glass windows. However, some of the saints who had traditionally been worshipped in the Ruhr region were also venerated by the Ruhr Poles. In particular, they included St. Joseph, who as a trained carpenter made for a credible patron saint for the labourers, and St. Barbara, patron saint of miners. Many of the Ruhr Polish societies founded during the early years of the 20th century bear the name of either Joseph or Barbara as patron saints.

Stanislaus Kostka

In the Ruhr region, Stanislaus Kostka [

Church windows dedicated to Stanislaus in Dortmund-Lütgendortmund and Dortmund-Eving were destroyed during air raids during the Second World War. Evidence shows that the window in Eving was funded by a Ruhr Polish society foundation. Today, the stained-glass window in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church in Recklinghausen-Suderwich is the only Stanislaus window to have survived [

Stanislaus Kostka was born on 28 October 1550 at Rostkowo palace in Masovia, 90 kilometres north of Warsaw. He came from a well-known noble family. In Vienna, Stanislaus attended the Jesuit college from 1564–1567. In 1566, he fell gravely ill and in his febrile state saw mystical visions. Thinking that he would die, he asked the St. Barbara, patron saint of a good death, for immediate assistance. Barbara then sent two angels to give him holy communion [ ]. In a second vision, the Virgin Mary appeared and placed the baby Jesus into his arms [ ]. The mother of God demanded that he enter the Jesuit Order. However, his father forbade him from taking such a step, and in fear of going against the wishes of the influential Polish family, the Austrian province of the monastic order refused to accept him into the Society of Jesus.

Stanislaus Kostka then fled Vienna for Bavaria, where he turned to Petrus Canisius, the provincial of the Jesuits in Upper Germany, and a committed standard bearer for the Catholic counter-reformation, for help. Canisius was very well-disposed towards the eager pupil whom he met in the Jesuit college in Dillingen on the Danube. He had him take an examination and sent him on to Rome, where in October 1567, Stanislaus was finally accepted into the Jesuit Order. However, the young novice died just ten months later, evidently from malaria, after suffering a severe attack of fever. His health had evidently been significantly weakened as a result of his exhausting journey on foot from Vienna to Dillingen, and then on to Rome. According to contemporary accounts, he was barefoot and wearing ragged peasant clothes.

During his short life, Stanislaus Kostka impressed those he met with his cheerful demeanour, personal modesty and deep piety. He was buried in the Sant’Andrea al Quirinale church in Rome. Soon afterwards, a religious cult grew up around him. He was beatified in 1605 and canonised in 1726. Stanislaus is the patron saint of young students, novices in the Jesuit Order, and of the severely ill and dying.

In 1674, after his intercession was said to have led to several victories in important battles, Stanislaus Kostka was proclaimed patron saint of the Polish-Lithuanian crown. He continues to be revered in his native country in particular, where there are several dozen churches dedicated to him. Of these, the most important are the monumental cathedral in Łódź [ , , ] and the Stanislaus Kostka church in the Warsaw suburb of Żoliborz, where during the communist era, the charismatic priest Jerzy Popiełuszko celebrated his “masses for the fatherland” (Msze za Ojczyznę) for two years before being murdered by officers of the Polish state security service in 1984 [ , ]. The painting in the centre of a baroque altar in the cathedral in Frombork shows Stanislaus Kostka, together with the statues of two other national Polish saints: Adalbert of Gniezno and another holy Stanislaus, who was bishop of Kraków in the 11th century [ , , ]. According to the legend, in 1410, this Stanislaus appeared in the firmament during the Battle of Tannenberg (Grunwald) and led the Polish-Lithuanian army to victory over the knights of the German Teutonic Order.

During the industrial era, emigrant Polish migrants took the Stanislaus Kostka cult with them. This was particularly the case in the United States, where nearly a million Poles, most of them from the eastern Prussian provinces, arrived between 1880 and 1910. Magnificent Stanislaus Kostka churches still bear witness to this influx of migrants today, such as those in Chicago, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh and New York [ , ]. There is also a church dedicated to Stanislaus in Namibia, in Keetmanshoop, which was consecrated in 1904 after the arrival of Polish emigrants from the German Empire, which governed this territory as a “colony” from 1884–1915 [ ]. Even further away, in River Hill in Australia, immigrants built a Stanislaus Kostka church in 1871 [ , ]. It is evident that this Polish national saint still retains his popularity all over the world today.

Certainly, the veneration of Stanislaus in Recklinghausen-Suderwich by the Ruhr Poles was also due to the fact that when as a Jesuit scholar in 1566 he fell severely ill, he turned to Saint Barbara for help, who is also a popular patron saint in the Rhenish-Westphalian mining region. According to the legend, the martyr Barbara was locked up in a cell in a tower by her father during the persecution of the Christians by the Romans. The miners of the Ruhr region saw parallels between her incarceration and their own working conditions, trapped underground in the dark at the coalface, constantly under the threat of death from a fire damp or coal dust explosion. There is also a parallel with the Stanislaus legend. In Vienna, the terminally ill pupil was isolated from the outside world, and his Protestant landlord refused to allow him to receive a Catholic priest. Saint Barbara then intervened, sending two angels who brought the eucharistic provisions for Stanislaus’ journey to his sickbed.