Stanislaus Kostka in Recklinghausen-Suderwich. The portrayal of a Polish national saint in a stained-glass window in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church

Mediathek Sorted

Ruhr Poles

From the final third of the 19th century onwards, the advancing industrialisation of coal mining and steel production led to an enormous demand for labour. From 1890 to 1914 in particular, countless people from near and far moved to the Rhenish-Westphalian mining region between the Ruhr and Lippe rivers. Nearly half a million of them came from the eastern Prussian provinces of Silesia, Posen and West and East Prussia, and had grown up speaking Polish as their native language. Aside from the Protestants from the Masuria region in East Prussia, most of these migrants were Catholics.

The majority of the immigrants headed for the newly developed coalfields in the northern Ruhr region. In 1890, around 5% of the population of the town of Recklinghausen were of Polish nationality; 20 years later, this figure had already grown to 23%. In the surrounding district, the Polish share of the population grew from 5.8% to 15.7% during the same period. In total, more than 53,000 people with Polish as their mother tongue lived in the town and district of Recklinghausen in 1910, constituting more than 10% of the Poles living in the Ruhr region overall.

These “Ruhr Polish” immigrants brought their own religious customs with them to their new homeland. Among the Catholics, this included the national Polish cult surrounding the Madonna of Częstochowa and the veneration of certain saints, such as Hedwig (Jadwiga), Adalbert (Wojciech), Kasimir (Kazimierz), Michael (Michał Archanioł) and Stanislaus (Stanisław) Kostka. Special societies of worship were founded and reverence for the saints was expressed artistically in the form of altarpieces, sculptures or stained-glass windows. However, some of the saints who had traditionally been worshipped in the Ruhr region were also venerated by the Ruhr Poles. In particular, they included St. Joseph, who as a trained carpenter made for a credible patron saint for the labourers, and St. Barbara, patron saint of miners. Many of the Ruhr Polish societies founded during the early years of the 20th century bear the name of either Joseph or Barbara as patron saints.

Stanislaus Kostka

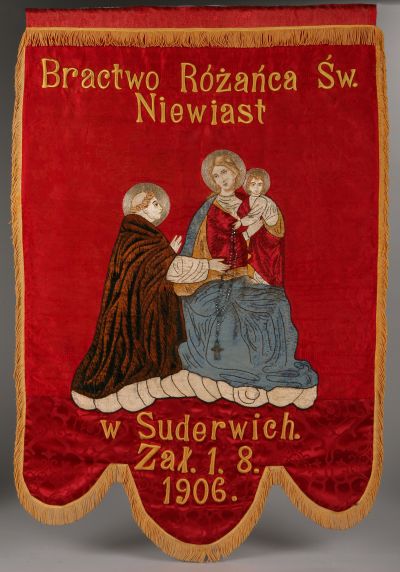

In the Ruhr region, Stanislaus Kostka [ ] was one of the most revered Polish national saints. There are records of Catholic societies worshipping Stanislaus in Duisburg-Marxloh, Mülheim-Styrum, Essen, Essen-Altenessen, Essen-Katernberg, Bottrop, Gelsenkirchen-Schalke, Herne, and Dortmund-Eving, as well as for Bruch, Röllinghausen, Hochlar and Suderwich on the fringes of Recklinghausen. Beautifully designed pennants also survive that were created for the societies in Bottrop and Altenessen [ , , , ].

Church windows dedicated to Stanislaus in Dortmund-Lütgendortmund and Dortmund-Eving were destroyed during air raids during the Second World War. Evidence shows that the window in Eving was funded by a Ruhr Polish society foundation. Today, the stained-glass window in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church in Recklinghausen-Suderwich is the only Stanislaus window to have survived [ ]. It is probably even the only church window in the entire Ruhr region that depicts a Polish national saint.

Stanislaus Kostka was born on 28 October 1550 at Rostkowo palace in Masovia, 90 kilometres north of Warsaw. He came from a well-known noble family. In Vienna, Stanislaus attended the Jesuit college from 1564–1567. In 1566, he fell gravely ill and in his febrile state saw mystical visions. Thinking that he would die, he asked the St. Barbara, patron saint of a good death, for immediate assistance. Barbara then sent two angels to give him holy communion [ ]. In a second vision, the Virgin Mary appeared and placed the baby Jesus into his arms [ ]. The mother of God demanded that he enter the Jesuit Order. However, his father forbade him from taking such a step, and in fear of going against the wishes of the influential Polish family, the Austrian province of the monastic order refused to accept him into the Society of Jesus.

Stanislaus Kostka then fled Vienna for Bavaria, where he turned to Petrus Canisius, the provincial of the Jesuits in Upper Germany, and a committed standard bearer for the Catholic counter-reformation, for help. Canisius was very well-disposed towards the eager pupil whom he met in the Jesuit college in Dillingen on the Danube. He had him take an examination and sent him on to Rome, where in October 1567, Stanislaus was finally accepted into the Jesuit Order. However, the young novice died just ten months later, evidently from malaria, after suffering a severe attack of fever. His health had evidently been significantly weakened as a result of his exhausting journey on foot from Vienna to Dillingen, and then on to Rome. According to contemporary accounts, he was barefoot and wearing ragged peasant clothes.

During his short life, Stanislaus Kostka impressed those he met with his cheerful demeanour, personal modesty and deep piety. He was buried in the Sant’Andrea al Quirinale church in Rome. Soon afterwards, a religious cult grew up around him. He was beatified in 1605 and canonised in 1726. Stanislaus is the patron saint of young students, novices in the Jesuit Order, and of the severely ill and dying.

In 1674, after his intercession was said to have led to several victories in important battles, Stanislaus Kostka was proclaimed patron saint of the Polish-Lithuanian crown. He continues to be revered in his native country in particular, where there are several dozen churches dedicated to him. Of these, the most important are the monumental cathedral in Łódź [ , , ] and the Stanislaus Kostka church in the Warsaw suburb of Żoliborz, where during the communist era, the charismatic priest Jerzy Popiełuszko celebrated his “masses for the fatherland” (Msze za Ojczyznę) for two years before being murdered by officers of the Polish state security service in 1984 [ , ]. The painting in the centre of a baroque altar in the cathedral in Frombork shows Stanislaus Kostka, together with the statues of two other national Polish saints: Adalbert of Gniezno and another holy Stanislaus, who was bishop of Kraków in the 11th century [ , , ]. According to the legend, in 1410, this Stanislaus appeared in the firmament during the Battle of Tannenberg (Grunwald) and led the Polish-Lithuanian army to victory over the knights of the German Teutonic Order.

During the industrial era, emigrant Polish migrants took the Stanislaus Kostka cult with them. This was particularly the case in the United States, where nearly a million Poles, most of them from the eastern Prussian provinces, arrived between 1880 and 1910. Magnificent Stanislaus Kostka churches still bear witness to this influx of migrants today, such as those in Chicago, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh and New York [ , ]. There is also a church dedicated to Stanislaus in Namibia, in Keetmanshoop, which was consecrated in 1904 after the arrival of Polish emigrants from the German Empire, which governed this territory as a “colony” from 1884–1915 [ ]. Even further away, in River Hill in Australia, immigrants built a Stanislaus Kostka church in 1871 [ , ]. It is evident that this Polish national saint still retains his popularity all over the world today.

Certainly, the veneration of Stanislaus in Recklinghausen-Suderwich by the Ruhr Poles was also due to the fact that when as a Jesuit scholar in 1566 he fell severely ill, he turned to Saint Barbara for help, who is also a popular patron saint in the Rhenish-Westphalian mining region. According to the legend, the martyr Barbara was locked up in a cell in a tower by her father during the persecution of the Christians by the Romans. The miners of the Ruhr region saw parallels between her incarceration and their own working conditions, trapped underground in the dark at the coalface, constantly under the threat of death from a fire damp or coal dust explosion. There is also a parallel with the Stanislaus legend. In Vienna, the terminally ill pupil was isolated from the outside world, and his Protestant landlord refused to allow him to receive a Catholic priest. Saint Barbara then intervened, sending two angels who brought the eucharistic provisions for Stanislaus’ journey to his sickbed.

Recklinghausen

The town of Recklinghausen was the main centre of the “Vest” of the same name. It had belonged to the territory governed by the archbishops of Cologne since the High Middle Ages. As a result, the population remained Catholic during the Reformation period. In 1815, the Congress of Vienna assigned the region to the Kingdom of Prussia, which was mainly Protestant. This led, among other things, to an influx of evangelical leaders and administrative officials. The beginning of the coal mining era saw a marked increase in the number of evangelical immigrants. Here, too, the Prussian “culture battle” led to considerable tensions between Protestants and Catholics in the wake of the founding of the German Empire in 1871. When the priest in Suderwich died in 1879, for example, several years passed before the Prussian government gave permission for a new occupant to fill the post. In this village, which was later incorporated into the town of Recklinghausen, this discrimination would not be forgotten for decades afterwards.

In 1856/57, the first pit fields for the Henriettenglück I/II/III coal mines to the south-east of the town were awarded to their new owners. In 1872, following the foundation of the Empire, they were renamed “King Ludwig I/II/III”. Ludwig II, the Bavarian monarch, remains popular today as the romantic “fairytale king” with his sumptuous palaces in Neuschwanstein, Herrenchiemsee and Linderhof. In Recklinghausen, the name was chosen as a reminder of the proclamation of the Prussian king Wilhelm I as German Kaiser, which had been initiated by a “Kaiserbrief”, an imperial letter written by Otto von Bismarck and signed by Ludwig II. The name of this coal mine therefore served as a symbol of patriotic Protestantism [ ].

The King Ludwig I/II/III coal mine began operations in 1885. At the turn of the century, more than half of the mine’s employees spoke Polish. In 1902, the Ludwig IV/V mine was opened six kilometres away. Its shafts had been sunk on the outskirts of Suderwich. In the bitterly cold post-war winter of 1946/47, this mine unexpectedly gained cultural importance as the supplier of “illegal” Ruhr coal to the Deutsches Schauspielhaus theatre in Hamburg. The theatre management demonstrated its gratitude by putting on guest performances in Recklinghausen. This marked the beginning of the world-famous “Ruhrfestspiele” theatre festival. The first performances were given in the Saalbau hall in Recklinghausen; later, a proper festival theatre was built in the town. The Hamburg State Opera also organised “Invalidenkonzerte” concerts in the Lohnhalle hall, where wages were once paid out, of the King Ludwig I/II/III mine as an expression of their special relationship with the miners [ , , , , , ].

The St.-Johannes-Kirche church in Suderwich

Suderwich already had its own church from around 1250, a small wooden building dedicated to St. John (St. Johannes) the Baptist. After being destroyed by fire, it was replaced in 1441 by a sandstone structure. A new bell tower was built in 1626, and a new aisle in 1821/22.

A handful of miners who worked at the collieries in the neighbouring towns had also been living in Suderwich since the 1870s. When at the end of the 19th century it became clear that the King Ludwig IV/V mine would go into operation, the influx of miners very quickly became a flood. Between 1900 and 1914 alone, the population of the village increased from 1,448 to 6,953. Already by 1899, the small village church was no longer able to house the large congregation, and the parish decided to build a larger one. The new church was designed by the architect Franz Lohmann, who also created the designs for four other churches in what is now part of the Recklinghausen municipal area [ , , , ].

“Suderwich Cathedral”, a spacious hall church with a 75-metre-high tower, was consecrated on 20 October 1904. The interior space was fitted with high-quality fixtures, most of which remain intact today: three neo-Gothic carved altars, four confessional booths and a large number of church benches. All the stained-glass windows have also remained intact – a real rarity in the Ruhr region. The church therefore remains a source of fascination as a work of sacred art overall. It is also an impressive reminder of the mining and cultural history in the Vest Ruhr mining region [ ].

In Suderwich, too, a large number of the immigrants were not of German nationality, but came from the Czech speaking regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and above all – with Polish as their native language – from the eastern Prussian provinces. From the early years of the 20th century onwards, services in the Catholic parish were therefore also held in Polish and Czech. In 1904, a padre from the Franciscan monastery in Dortmund visited Suderwich for individual appointments. Later, two Westphalian chaplains were stationed here, who had previously learned the languages spoken by the congregation: Heinrich Theißelmann (1905–1907) and Robert Zumloh (1910–1914).

The different nationalities were also reflected in the church societies that were established in Suderwich. For example, there are records of a St. Wenceslas society (for the Czechs) and a St. Stanislaus society (for the Poles). In 1909, Polish miners also founded a “St. Joseph workers’ association” (Arbeiterverein St. Josef). They did so in response to the refusal by the local “St. Barbara miners’ association” (Knappenverein Sankt Barbara), which had been founded in 1881, to accept immigrant workers as members. Apparently, the status-conscious German miners were unwilling to mingle with their Polish colleagues. During that time, St. Joseph was also the patron saint of a Ruhr Pole “Brotherhood of St. Rosary of the women in Suderwich”, of which a pennant labelled in Polish remains [ ]. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, there is also a window depicting Saint Stanislaus Kostka in the St.-Johannes-Kirche church, which was produced following the influx of Ruhr Polish Catholics to Suderwich [ ].

Stained-glass window cycle

The three stained-glass windows for the central apse behind the middle aisle of the neo-Gothic church in Suderwich were completed in 1904 by the stained-glass workshop run by Wilhelm Derix from Kevelaer. A further six windows for the adjacent choirs behind the two side aisles were installed in 1907. Each window is ten metres high and 2.20 metres wide. The windows are particularly well illuminated when the sun shines through during the morning. The workshop billed the congregation for 4,700 gold marks for the three windows in the main choir alone. According to the Suderwich author (and evangelical priest) Walter Zillessen, the bill was partially covered by the general vicariate of the bishopric of Münster. However, the costs were mainly borne by the church congregation. “As a result of the new mines and the sale of church lands to the mining companies, the congregation was not without financial means. In addition, there were the church societies at that time who were happy to contribute, as were wealthy individuals in the congregation.” (Zillessen, 1987)

Zillessen also assumes that the images portrayed in the windows were designed by the local priest, Heinrich Hauling. Hauling was considered an “art lover”; before his time in office in Suderwich (1884–1921), he was chaplain at Darfeld Palace in the Münsterland region, where he came into contact with the “Westphalian spiritual leadership at that time”. The aged priest (who was born in 1831) was enthusiastically supported in the church building project by his chaplain, Hermann Öchtering, who was otherwise responsible for the pastoral care of the immigrants, and who – unsuccessfully – campaigned in 1906 for the Polish miners to be accepted into the “German” miners’ associations. Given this context, it is likely that it was Öchtering who suggested that Stanislaus Kostka should be portrayed in the Suderwich window cycle.

The nine choir windows are a colourful testament to the religious affiliation of a Catholic Ruhr region community at the beginning of the 20th century. The presence of Stanislaus Kostka in this harmonious series of images is not the only reminder of the Ruhr Poles who once lived here. The highly symbolic representation of the transfiguration of St. Joseph was also included to reflect the pastoral care of the Poles, since in Suderwich, Jesus’ foster father was revered as a patron saint by not just one Polish society, but two.

Each of the nine choir windows shows a scene from the life of Jesus, the mother of God or St. Joseph in the upper section. The lower section of most of the windows contains images of saints. In the apse of the middle aisle, the crucifixion of Christ is the central element, flanked by depictions of the baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist and John the Baptist’s decapitation [ , , ]. The choir chapel behind the left-hand side aisle is dedicated to the mother of God. The central window celebrates her ascension to Heaven. To the left, Maria is shown as a young girl visiting the temple; to the right as Pietà, with her dead son in her lap. The central window also shows Adam and Eve being driven from Paradise [ , , , ].

The three stained-glass windows at the end of the right-hand side aisle are dedicated to St. Joseph. The right-hand window shows his carpentry workshop. To the left, we see Joseph explaining the holy scripture to his family – the mother of God and the boy Jesus [ , ].

The central window shows him as the patron saint of the church, surrounded by four angels presenting the insignia of the papal primate: two crossed keys, a shepherd’s crook with three crosses, St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and the tiara. The lower section of the window shows a peasant on the left-hand side and a miner on the right, both of whom look up to Joseph with folded hands. To the left, the bell tower of the village church in Suderwich has been added to the picture; to the right, a pit frame from the King Ludwig IV/V mine [ , ].

In this way, not only is Joseph venerated, but the papal claim of primacy in Recklinghausen-Suderwich is also shown. This claim is further underlined in the centre of the lower area of the window. Here, Pius IX (1792–1878) is shown on his throne, who in 1870 had a definition of papal “infallibility” set down in writing by the First Vatican Council. In his left hand, he holds a document bearing the inscription “Decretum 7 July 1871”. In this text, the Pope reports that the general sense of anxiety following the outbreak (in 1870) of the Franco-German War had led to a huge increase in the veneration of Joseph among believers. As a result, the Council fathers had implored him – “in these sombre times, to drive away all evil” – to more effectively ask for God’s mercy through the intercession of St. Joseph by declaring him Patronus Ecclesiae. He said that he had agreed to their request, and that on 8 December 1870, he had ceremonially declared the foster father of Jesus the patron saint of the entire Catholic Church.

In several cases, the saints represented in the lower section of the Suderwich choir window have been selected with the Ruhr region in mind. For example, Barbara, the patron saint of mining, is shown, as is Elizabeth, patron saint of charitable service [ ]. Stanislaus Kostka is portrayed in the right-hand side window of the main choir. He is flanked on the right by the famous religious teacher Thomas Aquinas, and to the left by the young martyr Tarcisius, who, according to popular legend, smuggled the sacred host to his incarcerated fellow believers at the time when Christians were being persecuted by the Romans [ ].

In the images shown in the windows, Stanislaus is shown holding a pilgrim’s rod with a St. James’s scallop in his left hand, indicating his pilgrimage on foot from Vienna to Rome. In his right arm, he holds the boy Jesus, whose universal rule is expressed by a small globe. This calls to mind the appearance of Mary before the feverish young Polish pupil in Vienna: in his mystical vision, the mother of God handed her son to him to hold.

Concluding comments

During the Counter-Reformation, the Jesuit novice Stanislaus Kostka, who died at such a young age, provided the ideal image of a saint with his passionate, uncompromising love for Jesus and the mother of God. The fact that – according to the Catholic version of the story – he offered military assistance to his home country from the next world also qualified him as a powerful patron saint of Poland. Even in the industrial age, this act of support in favour of national integration was still of major political significance, since between 1795 and 1918, there was no longer any such thing as a Polish state following its three territorial partitions.

From the end of the 19th century onwards, Polish migrants spread the Stanislaus cult all over the world. Reverence for the saint also became an important feature of their lives in the Rhenish-Westphalian mining region. This was certainly helped by the fact that thanks to Stanislaus’ legendary vision, a connection could be made to the veneration of St. Barbara, the patron saint of miners.

During that period, the cult surrounding Stanislaus Kostka arose against a tense political backdrop in which confessional, social and nationalist elements played a part. The choice of images for the church windows in Suderwich can also be interpreted with this in mind. The starting point here is the central Joseph window, which shows the foster father of Jesus as Ecclesiae Patronus . Here, the wishes of Pius IX are taken into account in a manner that demonstratively refers to the power of the papal primate over the Catholic church in Germany. At that time, in Protestant-dominated Prussia, “Ultramontanism” of this kind was regarded as an expression of insufficient loyalty to the fatherland.

The picture includes the village church and the pit frame of the King Ludwig IV/V mine, thus clearly placing the transfiguration of St. Joseph in Suderwich. Here, the carpenter from Nazareth is also the patron saint of the local farmworkers and miners. Two local societies document the fact that the Polish miners and their wives also venerated the foster father of Jesus.

From the perspective of the Prussian authorities, during the late imperial period, the Polish citizens were not only unreliable as a result of their Catholicism. It was their national identity in particular that made them the subject of suspicion. Despite various disagreements among German and Polish Catholics, they were united in their open rejection of the Protestant-dominated self-understanding of the state by their shared veneration of saints who were typical for the Ruhr region – both Joseph and Barbara – and by their committed support for Ultramontanism.

With the Joseph cult in mind, one can take another look at the Stanislaus window portrait: while no written confirmation is given that the window has been funded by a Polish organisation, it does express ultramontane Catholic piety and Polish national identity set against the context of the political environment at the time. Overall, therefore, the set of stained-glass windows in Suderwich is an impressive testament to the multi-faceted history of the Ruhr region, including the “Ruhr Poles” who lived there.

Thomas Parent, May 2024

Selected bibliography

“König Ludwig” working group in the Förderverein Bergbauhistorischer Stätten e.V. and Christoph Thüer (ed.): Unsere Zeche König Ludwig. Wiege der Ruhrfestspiele und mehr…, Werne 1905.

Burghardt, Werner: “Die polnischen Arbeiter sind … fleißig und haben einen ausgeprägten Erwerbssinn …”. Zur Geschichte polnischer Bergarbeiter in Recklinghausen, in: Bresser, Klaus und Christoph Thüer (ed.): Recklinghausen im Industriezeitalter, Recklinghausen 2000, p. 401–423.

Festschrift zum 50jährigen Jubiläum des katholischen Knappen- und Arbeitervereins St. Barbara, Recklinghausen 1932.

Haida, Sylvia: Die Ruhrpolen. Nationale und konfessionelle Identität im Bewusstsein und im Alltag 1871–1918, phil. diss. Bonn [mach.] 2012.

Schäfer, Joachim: Artikel Stanislaus Kostka, Ökumenisches Heiligenlexikon, https://www.heiligenlexikon.de//BiographienS/Stanislaus_Kostka.html (accessed on 28/1/2024).

Schröder, Heinrich: Fest- und Heimatschrift der Pfarrgemeinde St. Johannes Recklinghausen-Suderwich zum 50. Jahrestag der jetzigen Kirche am 20. Oktober 1904, Recklinghausen 1954.

Zillessen, Walter: Die Predigt der Bibelfenster von St. Johannes in Suderwich, Recklinghausen-Suderwich 1987.

Zillessen, Walter: Kirche im Zeitalter der Industrialisierung am Beispiel Suderwichs, in: Möllers, Georg and Richard Voigt: 1200 Jahre christliche Gemeinde in Recklinghausen, Recklinghausen 1990, p. 185–198.