Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

Mediathek Sorted

Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

There is a profusion of empty, tidy, well tended areas. Without people. Sure, an anonymous person or a group of visitors sometimes pops up, captured when they are inspecting part of the exhibition, which was expertly put together and which- as all the guide books will tell you - provides extensive information. But all of this constitutes a vague backdrop. They are guests from another world, strangers. There are no silhouettes or ghostly shadows of the main perpetrators of the terrible drama. This absence is perplexing and disturbing at the same time. The more I go from image to image, the more I am convinced that this absence is no coincidence. It must be the photographer’s intention in some way. At the very least, it represents a trail which entices the observer to follow it.

I have never been in Sachsenhausen and have never visited a concentration camp. I have not felt any need to visit there, but not because the existence of the camps and their history is inconsequential. Quite the opposite. Since my school days, and I belong to the generation that was fed books and knowledge about the Second World War in abundance, the experiences in the camps have raised a number of questions for me: questions about the people, about their culture and history, about their self-image, about the moral and social order which the people creates, and which they create in an uncompromising, concentrated and even brutal way. These were not historical questions; they were purely anthropological questions. The camp experiences constitute an unprecedented borderline experience, not the first and not the only one, but extreme and close enough in terms of time that they are not just repressed as an historical fossil that troubles one's peace of mind. I was aware of all that when I read books and when I watched films. So what would the visits have been able to add, apart from an emotional downpour on the paths of the crime, on the places of torture? This is all the more true because the encounters with the past at such places are not direct: the camp that we visit is not a real camp, our situation does not reflect in any way the situation faced by the victims. It does not reflect the executioners’ situation either. You can save yourself the trouble.

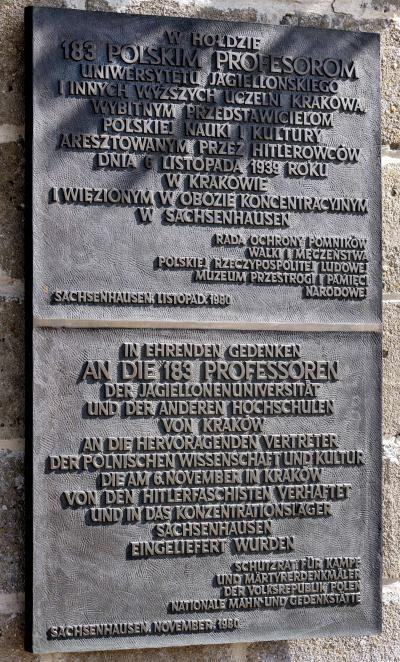

Was that a typical attempt on my part to rationalise my fear? Most definitely, yes. I have looked at Marian Stefanowski’s photographs of the Sachsenhausen camp with increasing interest. Possibly for the very reason that in this case we are dealing with a realisation that is conveyed gradually: we perceive the traces of the empirically inaccessible past through the vision, the perspective and the selection of someone else. As well as the question of the subject matter, the question of the medium is also raised, which in this case takes on the role of an emotional buffer. I found Stefanowski to be a discrete and transparent medium. Hidden behind his subject, he has created a cycle of completely neutral, detached and cool photos in which he dispenses with the need for artificial expressions and commentaries which could entice the observer into doing something. His photographic documentation subjugates itself completely to the place in question, is proficient and systematic. It shows memorials, general outlines, individual exhibits, commemorative plaques, sporadic groups of visitors and...a great deal of open space. Ordered, clean, well maintained space, which despite everything and despite the quiet is still enclosed by barbed wire and watchtowers as it was in the past. A cleared stage awaiting the next act of a drama? For me personally, this is not a metaphor, it is a deliberate moment of remembrance in which we find ourselves in the here and now. The last witnesses are dying out, the generational emotional and cognitive remoteness is growing. Ultimately, the memory of their experience is giving way before our very eyes to just our constructed memory. It is up to us to decide with whom, with what and in what way we fill this place that is devoid of people. It is up to us, the mysterious visitors who, depending on how great our own curiosity and how strong our moral principles, lend this memory a definitive form when we are confronted with this flood of dramatic information whilst being torn out of our daily routine. In confronting the problem, Marian Stefanowski leaves the final decision to the observer.