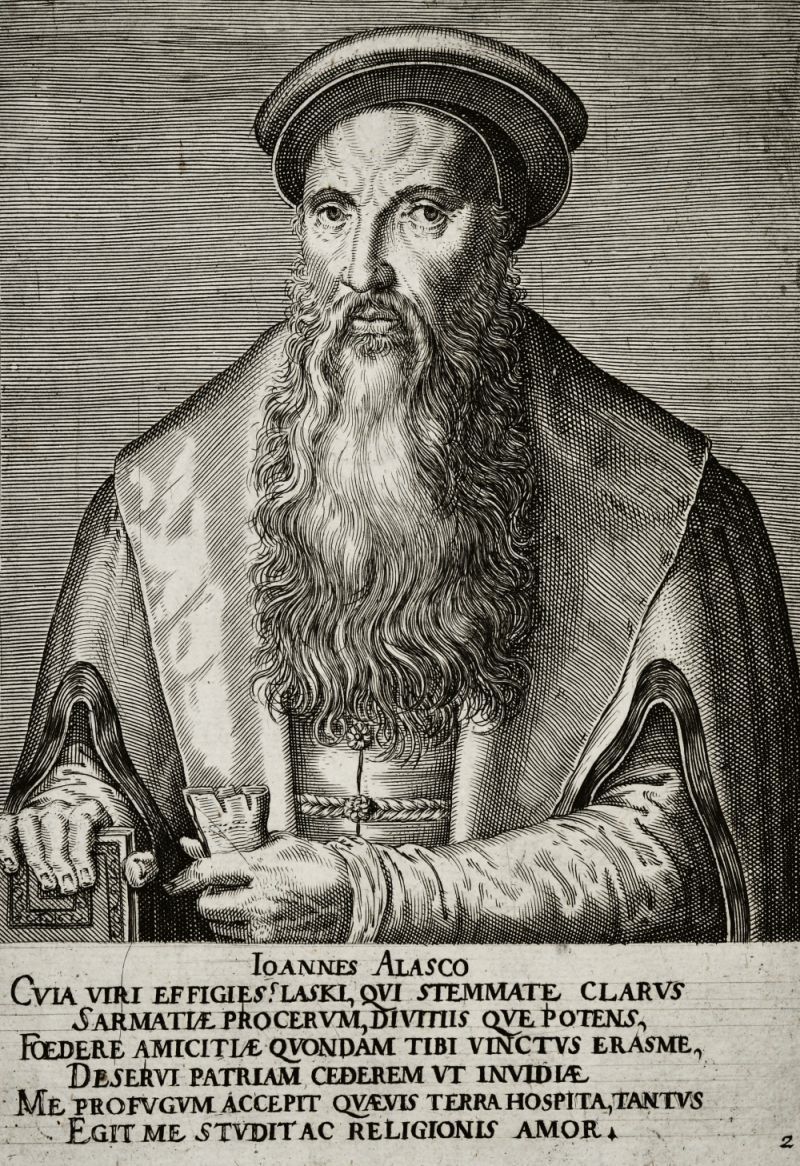

Johannes a Lasco

Mediathek Sorted

![Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Responsio ad uirule[n]tam, calumniisque Ac Mendaciis Consarcinatam hominis furiosi Ioachimi VVestphali Epistola[m] quandam, qua purgationem Ecclesiaru[m] Peregrinarum Francofor...](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/4_antwort_auf_joachim_westphal_1560.jpg?itok=Pd3diTmf)

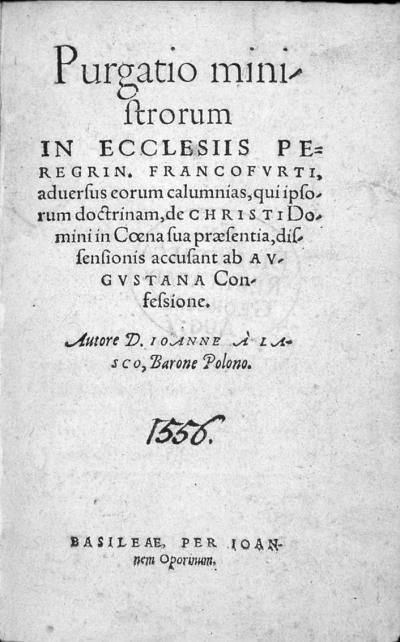

![Fig. 5: Three letters Fig. 5: Three letters - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Epistolae tres lectu dignissimae, de recta et legitima ecclesiarum benè instituendarum ratione ac modo: ad Potentiss. Regem Poloniae, Senatum, reliquos[que] Ordines, Basel 1556](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/5_drei_briefe_1556.jpg?itok=hQ0svO_N)

However, there were already signs of the breakdown that was to come in à Lasco’s life and career. In 1527, his brother Jarosław intervened in the succession of King Louis II of Hungary who died after the battle at Mohács against the Turks. Against the will of the Polish king, Jarosław entered into the services of the Hungarian nobleman and Voivoide of Siebenbürgen, John Zápolya (1487-1540), who, like the Habsburg Ferdinand of Austria (1503-1564), laid claim to the crown. After unsuccessful diplomatic missions in England and France, Jarosław travelled to Constantinople to ask Sultan Suleiman I for military support against Habsburg, and in 1528, as the Sultan’s military leader, he moved to Hungary with Turkish troops. The other members of the Łaski family were also drawn into the conflict: Stanisław supported his brother in the role of diplomat and military leader. In 1530, as a member of Zápolya’s delegation, John à Lasco took part in peace negotiations in Poznań between Suleiman and Ferdinand and later acted as Zápolya’s negotiator with King Sigismund. When the Primate died in 1531, à Lasco’s dedication to Zápolya, which ran contrary to the Polish king’s rapprochement towards Habsburg, obviously meant that he was not considered as his uncle’s successor to the office of Bishop.

In summer 1534, Jarosław, who had hoped that his activities in Hungary would yield him his own position of power, was imprisoned by Zápolya after many years of intrigue and discord with the Turks. It was not until spring 1535 that John, aided by a high-ranking Polish delegation headed up by the chief Polish military leader, Jan Amor Tarnowski (1488-1561), was able to free him after interventions with the kings of Poland, France and England and with Sultan Suleiman. Finally, in secret negotiations with Habsburg, à Lasco initiated the Łaski family’s change of allegiance to the Austrians, which seemed to be a politically opportune move in Poland, but which still did not yield him the desired office of Bishop.[11]

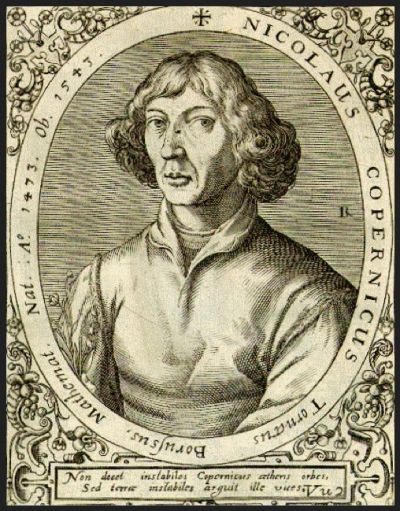

A Lasco, financially ruined by the Hungarian adventure and without the prospect of resuming his career, withdrew to one of the family’s country estates, Rytwiany near Staszów, halfway between Kraków and Lublin. He devoted himself once again to his humanist studies, which had been interrupted for almost ten years, and reestablished contact with Erasmus, who then died in July 1536. In April of the following year, à Lasco took possession of Erasmus’ library which was packed in three barrels. Just a few days later, he set off for the West. Travelling via Wroclaw and Dresden, he went to Leipzig, where he met with the humanist and Lutheran theologian Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560) who was teaching in Wittenberg and with whom à Lasco had already had contact. The two would remain in touch until the end of both their lives in 1560.

Endowed with an epistle from Elector John Frederick of Saxony which allowed him safe passage, à Lasco travelled on to Frankfurt am Main, where he encountered the Dutch monk and theology student, Albert Hardenberg (ca. 1510-1574). Hardenberg had been on his way to Italy but fell ill in Frankfurt and decided on the spur of the moment to complete his degree in Mainz; à Lasco accompanied him there. In December 1537, the two continued on to Leuven. Hardenberg taught at the university there and preached at the church of St. Michael. The two of them joined a circle of Leuven citizens in which Reformist writings influenced by Luther and Zwingli were read and discussed. Hardenberg came to the attention of the Catholic inquisition, was sued by the theologian faculty at the university and arrested in Leuven. However, in a long and drawn out process, he was acquitted and left the town in 1540 to withdraw to his original monastery, the Aduard Cistercian Abbey near Groningen.

[11] Ibid, p. 14-17; Jürgens 2002 (see Bibliography 3.), p. 92-125