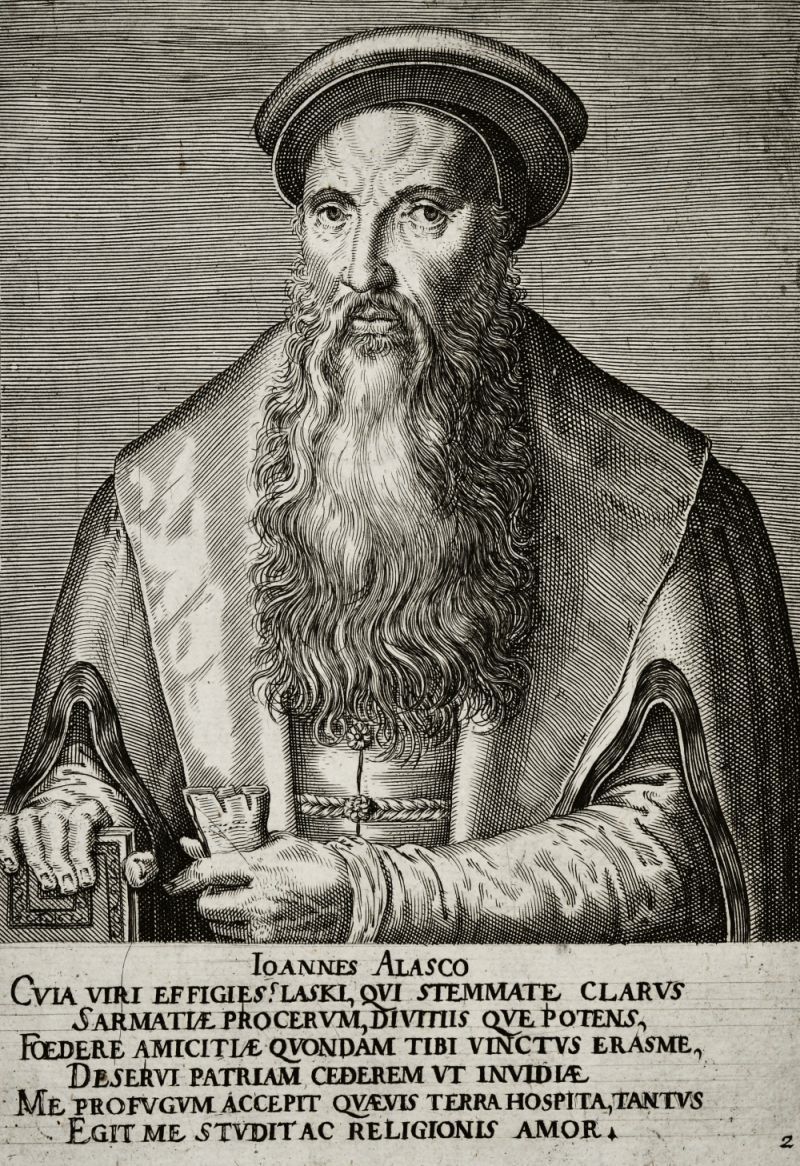

Johannes a Lasco

Mediathek Sorted

![Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Responsio ad uirule[n]tam, calumniisque Ac Mendaciis Consarcinatam hominis furiosi Ioachimi VVestphali Epistola[m] quandam, qua purgationem Ecclesiaru[m] Peregrinarum Francofor...](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/4_antwort_auf_joachim_westphal_1560.jpg?itok=Pd3diTmf)

![Fig. 5: Three letters Fig. 5: Three letters - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Epistolae tres lectu dignissimae, de recta et legitima ecclesiarum benè instituendarum ratione ac modo: ad Potentiss. Regem Poloniae, Senatum, reliquos[que] Ordines, Basel 1556](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/5_drei_briefe_1556.jpg?itok=hQ0svO_N)

In Paris, the Łaski brothers went their separate ways. In September, Jarosław once again travelled through Basel on his way back to Poland, taking with him letters to the Polish king in which Erasmus spoke critically about the German reformer Martin Luther (1483-1546). John did not make his way back to Poland until spring 1525, and on the way, he looked up Erasmus again in Basel and rented space in his extensive building complex where he remained for six months. Letters show that Erasmus and John à Lasco spent a lot of time with one another, that à Lasco paid for the running of the household, that they ate their meals together and that when they did, they had conversations about theological and political issues.[5]

The topics discussed by Erasmus and à Lasco would certainly have included the dissent about the Eucharist theology between the Swiss Reformers and Luther, the relationship between the authorities and the church, the Peasant’s Revolt and the situation in Poland. In 1524, in his writing entitled “De libero arbitrio” (On Free Choice) Erasmus stated his position against Luther. Whilst à Lasco was still in Basel, the reactions to Erasmus’s writing began to appear, and soon after his departure Luther’s response “De servo arbitrio” (On the Bondage of the Will) was published. Once back in Poland, à Lasco kept himself informed on its impact. He reported to Erasmus about the humanist circles in Poland and recommended that he send writings and letters to high-ranking Polish officials, clerics and the Polish king, which he did. A Lasco was also friendly with other humanists, such as the lawyer Bonifacius Amerbach (1495-1562), the universal scholar Heinrich Glarean (1488-1563) and the philologist Beatus Rhenanus (1485-1547). He gave them his patronage and later devoted writings to them.[6]

A Lasco decided to carry out another great act of patronage towards Erasmus which was agreed by contract: He acquired his library, including any books yet to be added, for an equivalent value of 400 gold guilders, but entrusted them to Erasmus to make full use of until the end of his life. A Lasco paid half of this amount, which was the equivalent of three to four annual salaries for a professor, immediately. A set of Greek manuscripts was excluded from the deal. A Lasco paid the remaining sum to the executors of Erasmus’ estate after his death, at which point the library was delivered to him in Kraków. Two years later, he managed to also acquire the remaining manuscripts.[7]

At his uncle’s request or at the order of the Polish king, à Lasco returned to Poland in spring 1526 after a stay in Italy in between. In Kraków, he resumed his role as Royal Secretary and was appointed Provost of Gnesen in the same year. In the service of the king, he participated in the parliamentary sessions of the Senate and the Sejm. His responsibilities as Provost of the cathedral included organising Bishops’ Synods. The Synod of 1527, which was led by the Primate, dealt amongst other things with the fight against Lutheran influences from Germany. Alongside his work as Provost, à Lasco also focused on humanist studies, promoted them at Kraków University, provided financial support to professors and students and tasked booksellers and couriers with acquiring books and manuscripts for him from as far afield as Russia. Thanks to his close connection to Erasmus, he was highly respected within the circle of Polish humanists and, of course, in addition to scholars, his official duties also brought him into close contact with politicians and clergy.[8] A book from his collection, a Bible concordance from 1526 in the Johannes à Lasco Library in Emden, with its magnificent cover adorned with a monogram and family crest, does not just bear testimony to his profound interest in books[9], but, according to Henning P. Jürgens, it also “radiates the self-confidence that à Lasco had at the time: He was a rich, talented, educated young man in an auspicious position, with the best contacts and the prospect of a career in the highest offices of Polish society.”[10]