Johannes a Lasco

Mediathek Sorted

![Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Responsio ad uirule[n]tam, calumniisque Ac Mendaciis Consarcinatam hominis furiosi Ioachimi VVestphali Epistola[m] quandam, qua purgationem Ecclesiaru[m] Peregrinarum Francofor...](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/4_antwort_auf_joachim_westphal_1560.jpg?itok=Pd3diTmf)

![Fig. 5: Three letters Fig. 5: Three letters - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Epistolae tres lectu dignissimae, de recta et legitima ecclesiarum benè instituendarum ratione ac modo: ad Potentiss. Regem Poloniae, Senatum, reliquos[que] Ordines, Basel 1556](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/5_drei_briefe_1556.jpg?itok=hQ0svO_N)

John à Lasco – A Polish Reformer in East Frisia

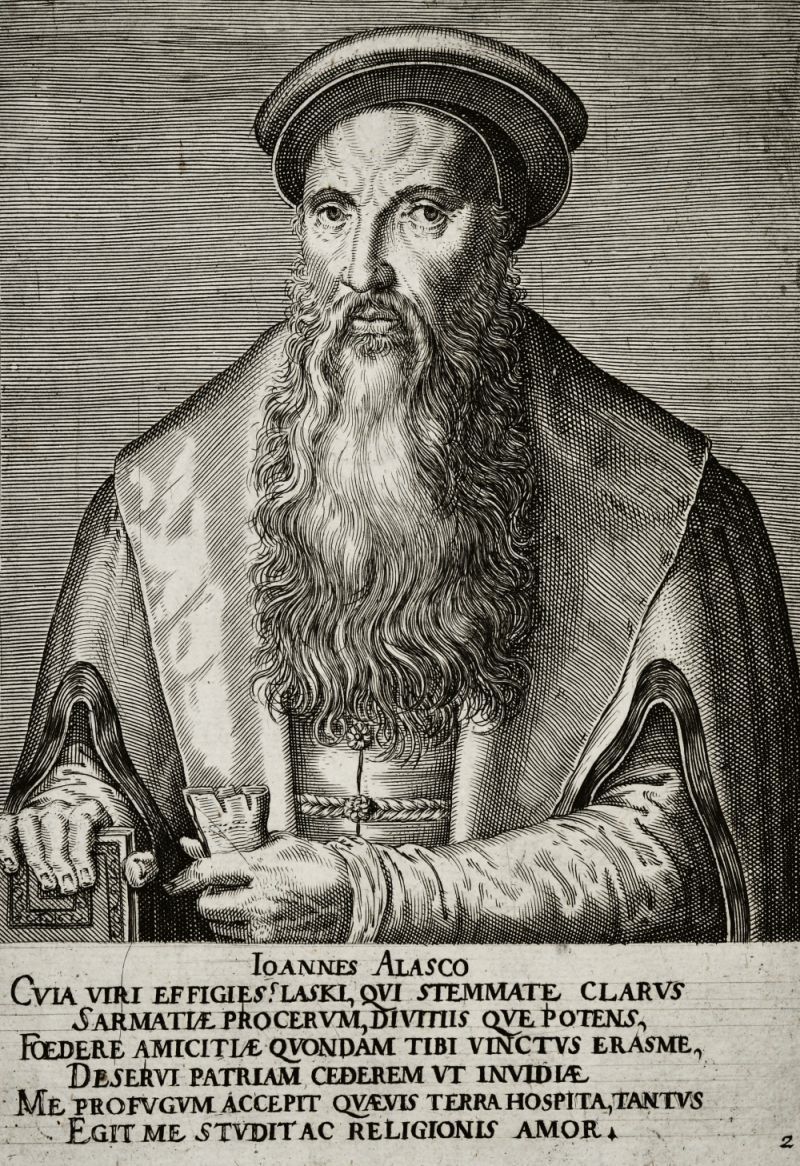

It is thought that Jan Łaski, the Latin form of which, Johannes à Lasco, is passed down from documents and writings of his day and which in recent times has become established in Germany,[1] was born in 1499 in what today is the district town of Łask, twenty kilometres to the south west of Łódź, into a family of prosperous and politically influential Polish nobility. The family owned three larger towns, Łask, Stryków and Bolesławiec, and around forty villages in various areas of Greater Poland and Lesser Poland. His father Jarosław was made Vovoide of Sieradz in 1511. His mother, Zuzanna z Bąkowej Góry, brought an extensive estate into the marriage. His eldest uncle on his father’s side, Andrzej, was a priest in Sieradz, Krakow, Poznań and Gnesen and died in 1512. His youngest uncle, Jan Łaski (the Elder, 1456-1531), was made Royal Secretary in 1501, Grand Chancellor in 1503 and Archbishop of Gnesen in 1510 and thus Primate of the church in Poland.[2]

Jan Łaski the Elder's prominent position meant that, under the reigns of Kings Aleksander Jagiellończyk (1461-1506) and Sigismund I (1467-1548), he was involved in domestic policy reforms and foreign policy achievements, such as the assertion of the Polish suzerainty over the German order or the marriage of the King to the Italian Princess Bona Sforza (1494-1557), but he was also involved in discussions about Poland’s relationship with the succession in Hungary and with the House of Habsburg. As Archbishop he took part in the fifth Lateran council in Rome in 1512-17, convened Provincial Synods and repressed the first sways of the Reformation in Poland.[3] Within his family, the Primate took care of all his brother Jarosław’s children: He used dowries to facilitate the marriages of his three nieces to noblemen. He brought his nephews Jarosław (*1496), Jan and Stanisław (*1501) to his court in Kraków where he afforded them an extensive humanist education. During the Roman Lateran Council, the Primate sent all three nephews to study at the universities in Rome, Bologne and Padua from 1513.

John stayed in Italy for six years from the age of 14. During this time, his uncle obtained ecclesiastical benefices for him in Poland, which meant that he more than enough income from spiritual offices and titles, some of which were in Gnesen and Kraków. When he returned to Poland in spring 1519, not only was he financially secure, he was also predestined for the highest secular and ecclesiastical offices and privileges. In 1521, he was ordained a priest, elected dean of Gnesen and appointed Royal Secretary.[4]

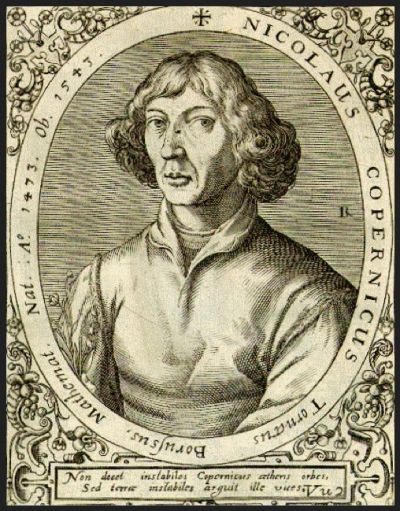

At a young age, Jarosław, the elder brother, was sent on royal assignments and on diplomatic missions abroad. In 1520/21, he and a Polish delegation attended the coronation of Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) in Bologna and during his trip he met the humanist Augustinian canon and priest Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466/69-1536) twice, once in Cologne and once in Brussels. His writings had been printed in Poland as early as 1518, predominantly in Kraków where they had been well received. In January 1524, Jarosław was sent to the French court in Paris and was accompanied by John and Stanisław. The Łaski brothers travelled via Switzerland, where they met the reformer Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) in Zurich and visited Erasmus at his property in Basel. In 1544, John would later say that it was Erasmus “that made me turn to religious matters, yes, he was the first to start to teach me true religion”.

In Paris, the Łaski brothers went their separate ways. In September, Jarosław once again travelled through Basel on his way back to Poland, taking with him letters to the Polish king in which Erasmus spoke critically about the German reformer Martin Luther (1483-1546). John did not make his way back to Poland until spring 1525, and on the way, he looked up Erasmus again in Basel and rented space in his extensive building complex where he remained for six months. Letters show that Erasmus and John à Lasco spent a lot of time with one another, that à Lasco paid for the running of the household, that they ate their meals together and that when they did, they had conversations about theological and political issues.[5]

The topics discussed by Erasmus and à Lasco would certainly have included the dissent about the Eucharist theology between the Swiss Reformers and Luther, the relationship between the authorities and the church, the Peasant’s Revolt and the situation in Poland. In 1524, in his writing entitled “De libero arbitrio” (On Free Choice) Erasmus stated his position against Luther. Whilst à Lasco was still in Basel, the reactions to Erasmus’s writing began to appear, and soon after his departure Luther’s response “De servo arbitrio” (On the Bondage of the Will) was published. Once back in Poland, à Lasco kept himself informed on its impact. He reported to Erasmus about the humanist circles in Poland and recommended that he send writings and letters to high-ranking Polish officials, clerics and the Polish king, which he did. A Lasco was also friendly with other humanists, such as the lawyer Bonifacius Amerbach (1495-1562), the universal scholar Heinrich Glarean (1488-1563) and the philologist Beatus Rhenanus (1485-1547). He gave them his patronage and later devoted writings to them.[6]

A Lasco decided to carry out another great act of patronage towards Erasmus which was agreed by contract: He acquired his library, including any books yet to be added, for an equivalent value of 400 gold guilders, but entrusted them to Erasmus to make full use of until the end of his life. A Lasco paid half of this amount, which was the equivalent of three to four annual salaries for a professor, immediately. A set of Greek manuscripts was excluded from the deal. A Lasco paid the remaining sum to the executors of Erasmus’ estate after his death, at which point the library was delivered to him in Kraków. Two years later, he managed to also acquire the remaining manuscripts.[7]

At his uncle’s request or at the order of the Polish king, à Lasco returned to Poland in spring 1526 after a stay in Italy in between. In Kraków, he resumed his role as Royal Secretary and was appointed Provost of Gnesen in the same year. In the service of the king, he participated in the parliamentary sessions of the Senate and the Sejm. His responsibilities as Provost of the cathedral included organising Bishops’ Synods. The Synod of 1527, which was led by the Primate, dealt amongst other things with the fight against Lutheran influences from Germany. Alongside his work as Provost, à Lasco also focused on humanist studies, promoted them at Kraków University, provided financial support to professors and students and tasked booksellers and couriers with acquiring books and manuscripts for him from as far afield as Russia. Thanks to his close connection to Erasmus, he was highly respected within the circle of Polish humanists and, of course, in addition to scholars, his official duties also brought him into close contact with politicians and clergy.[8] A book from his collection, a Bible concordance from 1526 in the Johannes à Lasco Library in Emden, with its magnificent cover adorned with a monogram and family crest, does not just bear testimony to his profound interest in books[9], but, according to Henning P. Jürgens, it also “radiates the self-confidence that à Lasco had at the time: He was a rich, talented, educated young man in an auspicious position, with the best contacts and the prospect of a career in the highest offices of Polish society.”[10]

However, there were already signs of the breakdown that was to come in à Lasco’s life and career. In 1527, his brother Jarosław intervened in the succession of King Louis II of Hungary who died after the battle at Mohács against the Turks. Against the will of the Polish king, Jarosław entered into the services of the Hungarian nobleman and Voivoide of Siebenbürgen, John Zápolya (1487-1540), who, like the Habsburg Ferdinand of Austria (1503-1564), laid claim to the crown. After unsuccessful diplomatic missions in England and France, Jarosław travelled to Constantinople to ask Sultan Suleiman I for military support against Habsburg, and in 1528, as the Sultan’s military leader, he moved to Hungary with Turkish troops. The other members of the Łaski family were also drawn into the conflict: Stanisław supported his brother in the role of diplomat and military leader. In 1530, as a member of Zápolya’s delegation, John à Lasco took part in peace negotiations in Poznań between Suleiman and Ferdinand and later acted as Zápolya’s negotiator with King Sigismund. When the Primate died in 1531, à Lasco’s dedication to Zápolya, which ran contrary to the Polish king’s rapprochement towards Habsburg, obviously meant that he was not considered as his uncle’s successor to the office of Bishop.

In summer 1534, Jarosław, who had hoped that his activities in Hungary would yield him his own position of power, was imprisoned by Zápolya after many years of intrigue and discord with the Turks. It was not until spring 1535 that John, aided by a high-ranking Polish delegation headed up by the chief Polish military leader, Jan Amor Tarnowski (1488-1561), was able to free him after interventions with the kings of Poland, France and England and with Sultan Suleiman. Finally, in secret negotiations with Habsburg, à Lasco initiated the Łaski family’s change of allegiance to the Austrians, which seemed to be a politically opportune move in Poland, but which still did not yield him the desired office of Bishop.[11]

A Lasco, financially ruined by the Hungarian adventure and without the prospect of resuming his career, withdrew to one of the family’s country estates, Rytwiany near Staszów, halfway between Kraków and Lublin. He devoted himself once again to his humanist studies, which had been interrupted for almost ten years, and reestablished contact with Erasmus, who then died in July 1536. In April of the following year, à Lasco took possession of Erasmus’ library which was packed in three barrels. Just a few days later, he set off for the West. Travelling via Wroclaw and Dresden, he went to Leipzig, where he met with the humanist and Lutheran theologian Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560) who was teaching in Wittenberg and with whom à Lasco had already had contact. The two would remain in touch until the end of both their lives in 1560.

Endowed with an epistle from Elector John Frederick of Saxony which allowed him safe passage, à Lasco travelled on to Frankfurt am Main, where he encountered the Dutch monk and theology student, Albert Hardenberg (ca. 1510-1574). Hardenberg had been on his way to Italy but fell ill in Frankfurt and decided on the spur of the moment to complete his degree in Mainz; à Lasco accompanied him there. In December 1537, the two continued on to Leuven. Hardenberg taught at the university there and preached at the church of St. Michael. The two of them joined a circle of Leuven citizens in which Reformist writings influenced by Luther and Zwingli were read and discussed. Hardenberg came to the attention of the Catholic inquisition, was sued by the theologian faculty at the university and arrested in Leuven. However, in a long and drawn out process, he was acquitted and left the town in 1540 to withdraw to his original monastery, the Aduard Cistercian Abbey near Groningen.

A Lasco’s rift with the Catholic church and with his ecclesiastical ministries in Poland was even more radical: Within the circle of the Leuven Reformers, he got to known a Ms Barbara, “pauperculam sine ulla dote uxorem” (a poor woman without any dowry), and married her at the beginning of 1540. In April the news of the marriage reached King Sigismund in Poland who immediately sought the opinion of the Pope about a possible revocation of all offices and benefices of the “Lutheran” John à Łaski. By the middle of the year, à Lasco’s marriage was common knowledge in Poland, and by the end of the year all of his appointments and revenues had already been redistributed. In Leuven, he now also had to fear persecution by the Inquisition. A Lasco and his wife left the city at the same time as Hardenberg and travelled to Emden, which was the principle city of the county of East Frisia with 3,000 inhabitants and was beyond the dominions of the Habsburgs. The acting Regent, Enno II (1505-1540), was known for his liberal religious policy and various church reforms, not all of which had succeeded. Soon after à Lasco’s arrival, the Regent offered him the position of Superintendent of East Frisia. However, à Lasco initially rejected the offer.[12]

When Jarosław fell ill on his way back from Constantinople and was lying on his death bed, à Lasco once again travelled to Poland. After his brother’s death in December 1541, he made an attempt to be reappointed to his lost offices. He pledged an oath before the cathedral chapter in Kraków, that, according to Jürgens, he “had not strayed from the teachings of the Catholic church”[13] but he kept silent about his marriage. As a consequence of this “Confessio”, his offices were restored in March 1542 and he was reimbursed for the income that he had been denied. Jürgens suspects that, along with his tangible financial interest, à Lasco’s motivation for this procedure was “to be able to implement his reformist-humanist ideals in the Polish church” with the help of the restored offices.[14] However, when à Lasco once again saw no prospect of a Bishop’s office, he returned to Emden at the beginning of May.[15]

Around the turn of the year 1542/43, Anna von Oldenburg (1501-1575), the widow of Enno II and Regent for her minor sons, appointed him Superintendent of the East Frisian church which, at this time, was widely disorganised. This time à Lasco accepted. In spite of an existing church order, different liturgical forms and Eucharist rituals were being practised by the Protestants, based on either Luther or Zwingli, and the teaching differed from preacher to preacher and from village to village. Catholic mass was read in the monasteries. East Frisia saw many new arrivals of Protestant congregations and Baptists from the Netherlands as religious refugees.[16]

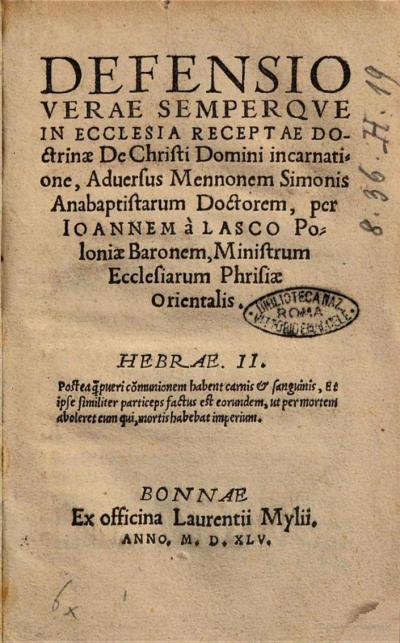

To differentiate the Protestant church from the Catholics and the Baptists, à Lasco chose disputation, a common measure of the time, which involved scholarly debate, in which the participants, based on the Bible, were supposed to provide evidence of the correctness of their belief and their teaching. The Catholic monks avoided these discussions and, as a result, were no longer allowed to preach or baptise. During the course of the 16th century they left East Frisia. In January 1544, a religious discussion of this kind was held with the Baptists, in particular Menno Simons (1496-1561), in which the aim was to reach a consensus about the original sin and the doctrine of justification, that is to say, the question of whether the justification of the sinner before God can be achieved by good deeds or merely through belief; no agreement could be reached about the incarnation of Christ and the offices of the church. However, the parties parted amicably. Menno left Emden a few months later and went to Cologne; however, large numbers of his followers, who at this time were already called “Mennonites”, remained in East Frisia. In 1545, à Lasco wrote a paper in which he defended his views on the incarnation of Christ against those of Menno (Fig. 1).[17] No agreement was reached with David Joris (1501/02-1556), the leader of the mystic-spiritualist school of thought among the Baptists. Instead of having all Baptists expelled from East Frisia, à Lasco embarked on difficult and time-consuming discussions with each of the religious refugees arriving from the Netherlands.

As organisational measures intended to stabilise the East Frisian church, à Lasco instigated the founding of a Church Council for each congregation and the church discipline for the members of the congregation and ordered all images, altars and Catholic requisites to be removed from the churches. The Church Council, which he introduced around the turn of the year 1543/44 for the Great Church in Emden, was made up of the preachers and four Elders elected from the congregation. The Church Council exerted church discipline on the members of the congregation, a discipline which demanded good behaviour in daily life, in marriage, towards neighbours and proper housekeeping. For anyone who was drunk, swore in public or committed other nuisances, the Church Council could impose penalties or exclusion from the Eucharist as a punishment. A Lasco managed to convince Countess Anna to abolish idolatry, i.e. image veneration, and, consequently, she had the majority of religious images and objects removed from the Great Church. He made sure that these measures were enforced in rural congregations by visitations, i.e. by personal visits to the village churches and their preachers.[18]

As a further step towards unification, à Lasco created “Coetus” (lat. assembly), a weekly meeting of preachers which took place in Emden in the summer half-year and at which theological issues were discussed. The suitability, teaching and lifestyle of newly arrived theologians were examined in mutual discussions. Using a compromise formula, the “moderatio doctrinae”, à Lasco attempted to emphasise the commonalities and to push back on the contentious questions, such as the dispute about the Eucharist, which was the problem discussed among the Reformers, Luther’s followers and Zwingli’s followers as to how Christ’s presence in the Eucharist was to be considered. However, the differences, particularly between the Reformers and the Lutherans, were so severe that the Coetus in its original form collapsed and only survived as a meeting of Reformist preachers, which still exists today. According to Jürgens, à Lasco, who corresponded with leading theologians of his time, such as Melanchthon, proved overall “to be less the profound theologian […], and more the capable organiser, who created functional and lasting committees and councils”.[19]

However, the reforms achieved were not to last. In 1546/47, Emperor Charles V campaigned on the Danube and in Saxony-Thuringia against an alliance of Protestant sovereigns and cities, the Schmalkaldic League, in order to repress the Reformation and he kept the upper hand. Following this, he passed a religious interim in the Augsburg Diet of 1548, an interim solution so to speak, in which he declared the Catholic mass, the old religious holidays and the veneration of saints to be binding but conceded the marriage of priests and the lay chalice to the Protestants. The Habsburg-Spanish Netherlands then increased its pressure on Countess Anna to push the interim through in East Frisia as well. She introduced a special form and dismissed à Lasco as Superintendent. A Lasco in the meantime had acquired the Abbingwehr estate to the northwest of Emden for his growing family.

His experienced this renewed upheaval in London to where Duke Albrecht of Prussia (1490-1568) had sent him as a negotiator to mediate an alliance of the Protestant princes with the English monarchy and other monarchies against the Emperor. When à Lasco returned to Emden in August 1549, he had already been dismissed and so continued on to Königsberg on a diplomatic mission. From there, he tried to win over the Polish king Sigismund II Augustus (1520-1572) to a Protestant alliance as well. The king however would not be convinced to turn against the Emperor. Since a longed for return to Poland seemed out of the question, à Lasco accepted an offer from the London Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) to support him in reforming the English church. Cranmer was part of the Council of Regents under the still minor King Edward VI. Endowed with a letter of recommendation for Duke Albrecht and a testimony from Countess Anna, à Lasco, attended by a large group of the Emden congregation, set out for England via Bremen and Hamburg, finally arriving in April 1550.[20]

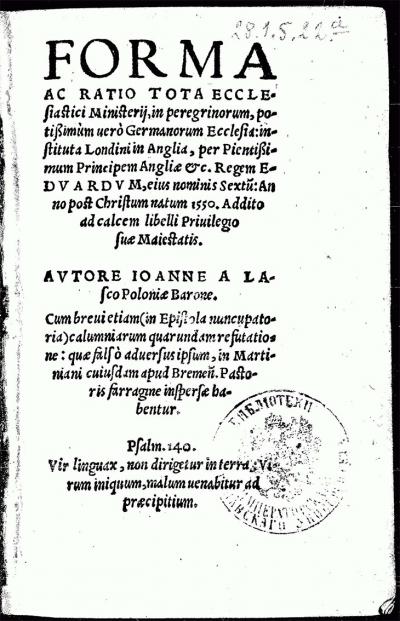

In London he was immediately appointed Superintendent of the refugee congregations who had emigrated to England from Germany, the Netherlands, France and Italy to escape religious persecution and had now been given the building of the Austin Friars Augustine monastery, which had been dissolved in 1538 and which lay six-hundred metres to the east of the bishop’s church St. Paul’s, for them all to use together. A charter from July 1550 awarded the congregations the right to organise themselves differently to the rite and rules of the English church.[21] A Lasco drafted a church order for London which appeared as a Latin version in 1555 (Fig. 2a, b) and in German in 1565[22] and was presumably based on the (unsustained) Emden church order. It governed the organisation of the congregation, the responsibilities of the preachers, Deacons and Elders, described the church discipline, the Coetus of the preachers and contained the liturgy and sermons. The London church order is considered à Lasco’s most important work and would, according to Jürgens, go on to influence the organisation of Reformed churches the world over: “The London order allowed the Polish humanist, who found his way to the Reformed church in East Frisia, to have an impact on Dutch Protestantism, in particular.”[23]

When à Lasco’s wife died of an infection, he married a Ms Katharina from the London congregation. But he did not stay there very long either. In summer 1553, Edward VI died at the age of sixteen. His successor to the throne, Mary I (1516-1558) was a Catholic who repealed the religious laws passed under Edward, reinstated the rite and teaching of the Catholic church and, from 1555, had Protestants, including priests and bishops, and Archbishop Cranmer in the following year, burnt at the stake as heretics. In September of the same year, à Lasco fled with 170 members of the congregation on two freighters to Denmark. However, the Lutheran King Christian III (1503-1559) turned the refugees away because he was unable to reach an agreement with the Reformers in the dispute over the Eucharist and they did not want to submit to the Danish church order. So à Lasco travelled to Emden where he managed to persuade Countess Anna to accept the London refugees, who arrived in East Frisia in spring 1554 after months of wandering aimlessly from Copenhagen via Lutheran towns on the German Baltic coast which did not want to accept them either.

A Lascos influence dwindled soon after the arrival of the London group of refugees. Countess Anna had now assumed a mediatory role between the various theologian positions, whilst à Lasco had become uncompromising as a result of his experiences in London and Denmark. When the Emden Catechism, which was the handbook for the teaching of fundamental questions of faith, was published in 1554, a hard fought compromise was reached between à Lasco and the Emden preachers. However, when the Spanish-Dutch court in Brussels repeatedly protested against à Lasco’s presence in Emden, Countess Anna decided to expel him. As a result, he left for Frankfurt am Main.

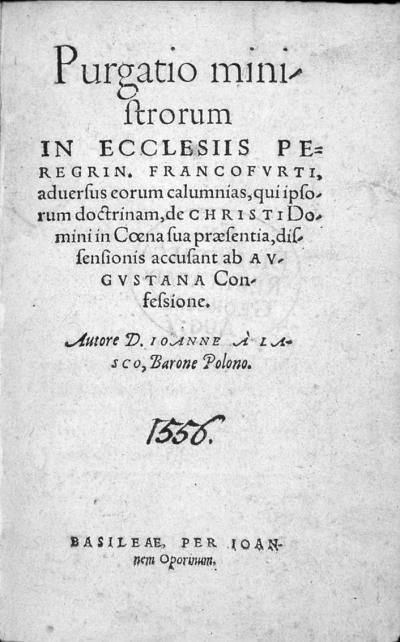

In Frankfurt as well, the dispute about the Eucharist erupted between the local Lutheran preachers and the reformed Dutch, Walloon and English religious refugees. A Lasco joined the Dutch congregation and acted as its spokesperson in the face of the Frankfurt Council. During this time, the Lutheran pastor from Hamburg Joachim Westphal (1510-1574), who had already attacked à Lasco during his stay in Denmark and had expelled the transient group of London refugees from Hamburg, published a writing against à Lasco, “Defensio adversus insignia mendacia Joannis à Lasco” (Defence against the outrageous lies of John à Lasco), in which he accused his congregations of breaching the imperial and religious peace concluded in Augsburg in 1555 between Emperor Charles V and the Lutheran imperial estates. In a “purgatory writing of the preachers of the refugee congregations”“[24] (Fig. 3) à Lasco rejected this accusation and would later react one last time, when in Poland again and at the end of his life, with a “response to the poisonous epistle patched together from hypocrisy and lies from the wild people of Westphalia with which he intends to slam the Purgatio of the Frankfurt refugee congregations”[25] (Fig. 4).

A Lasco was already thinking of returning to Poland. He wrote letters to important noblemen and devoted the edition of the London church order that was published in Frankfurt in 1955 to the Polish King Sigismund II. (Fig. 2 b). In 1556, he also had the letters which he had addressed to the lower nobility and the Polish Senate published, and with these “Epistolae tres lectu dignissimae” (three very worthy letters to read) he also informed the general public of his opinion that “the church should be well set up in a correct and legitimate way”[26] (Fig. 5). He received positive reactions from influential Polish nobility, such as the Lithuanian imperial prince Mikołaj Radziwiłł (1515-1565) and the Synod of Polish Reformers, who met in Pińczów in April 1556 in Poland and asked à Lasco to return. On 21 October, the same day as the Frankfurt Council expelled the refugee congregations, à Lasco set off for Poland. He arrived in Lesser Poland in December after stopping in Kassel, where he had talks with Landgrave Philipp I of Hessen (1504-1567), Wittenberg, where he attended an address by Melanchthon and met Polish students, and Wroclaw, where he lay in bed with a fever.

However, because the King reacted indignantly to à Lasco’s return and church advisers wanted to expel the Reformer, he retreated to Pińczów where he met with representatives of the Protestants in Kraków. The ideas of the Swiss Reformers and of the Frenchman John Calvin (1509-1564) had been particularly widespread amongst the nobility, whilst Luther remained unpopular in Poland. Many Protestant schools of thought, of which the Czech Brethren, the successor of the Hussites, were one, were becoming more influential but were disorganised and saw à Lasco as a unifying figure. In spring 1557, à Lasco travelled to Wilna to see Prince Radziwill and also met King Sigismund, who received him amicably and allowed him to hold religious services, but rejected a reform of the church. In Krakow, à Lasco preached in public until the cathedral chapter forbade it. A Lasco then settled in Pińczów where he held synods and assemblies of preachers and transformed the town into the centre of the Reformers in Lesser Poland.

In Pińczów, à Lasco got the basic structures of the Reformed church in Poland off the ground by introducing the election of Elders and Deacons and the church discipline, and by initiating a Polish translation of the Bible, the wording of a standardised Reformed confession and a catechism based on the Emden example. During his active years, around sixty Reformed congregations rose up in Lesser Poland. Attempts to bring about a unification with the Protestants in Greater Poland, the Lutherans and the Czech Brethren failed due to the dispute over the Eucharist. The Bishop of Ermland Stanisław Hozjusz (1504-1579), as the representative of the Catholic church, published polemic writings against à Lasco, in the aftermath of which, Poland as a whole remained Catholic. Following a dispute about the Trinity of God and the divine nature of Christ, the Polish Reformers split into a Reformed and a Unitarian church. Bedridden from the beginning of 1559, à Lasco was still writing polemic pamphlets against Hosius. He died in Pińczów on 8 January 1560.

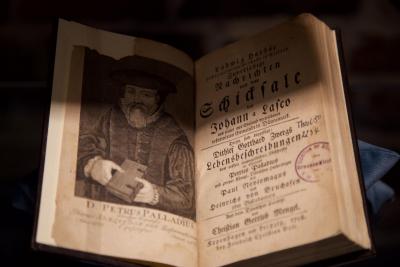

Today, the Johannes à Lasco Library in Emden commemorates the Polish Reformer in Germany. Since 1995, the library has been housed in what was à Lasco’s domain, the Grand Church in Emden. The modern new building has been integrated into the ruins of the “Moederkerk” of Reformist Protestantism which was destroyed in the Second World War (Fig. 6). The collections date back to à Lasco’s time. In 1559, the church Elder of the Reformed congregation, Gerhard tom Camp, left his books to the pastors for theological study. Originally housed in a private house and decimated significantly in a storm surge in 1570, they have since been stored in the consistory chamber of the Grand Church. In 1574, Albert Hardenberg’s library was added. Hardenberg was appointed Reformed pastor of the Grand Church in 1567, seven years after à Lasco's death. Continually expanded over the centuries by bequests from theologians, the library was relocated before the bombing of the Grand Church in 1943. Today it comprises a special library dedicated to Reformed Protestantism and to the history of the confession of the early modern period, 160,000 books, extensive archives and manuscripts.[27] Among these are also handwritten documents and first editions of books by John à Lasco as well as a portrait painted after 1555 that possibly served as the template for the copperplate engraving by Philips Galle (cover picture) a decade later.[28]

(to be continued)

Axel Feuß, November 2017

Literature:

1. Henning P. Jürgens: Johannes à Lasco, 1499-1560 – ein Europäer des Reformationszeitalters = Publications of the Johannes à Lasco Library, Grand Church Emden, 2, Wuppertal 1999

2. Henning P. Jürgens: Johannes à Lasco. Ein Leben in Büchern und Briefen. An exhibition at the Johannes à Lasco Library, Emden, Wuppertal 1999

3. Henning P. Jürgens: Johannes à Lasco in Ostfriesland. Der Werdegang eines europäischen Reformators = Spätmittelalter und Reformation, Neue Reihe 18, Tübingen 2002

4. Christoph Strohm (Publisher): Johannes à Lasco (1499-1560). Polnischer Baron, Humanist und europäischer Reformator. Contributions to the international symposium of 14-17 October 1999 in the Johannes à Lasco Library Emden, Tübingen 2000

5. Emden = Orte der Reformation, 13, published by J. Marius J. Lange van Ravenswaay, Klaas-Dieter Voß and Wolfgang Jahn, Leipzig 2014

6. J. Marius J. Lange van Ravenwaay: Testimonies of the great past, in: Die fantastischen Vier = Politik und Kultur. Dossier Reformationsjubiläum No. 2, Berlin 2017, page 48 f.