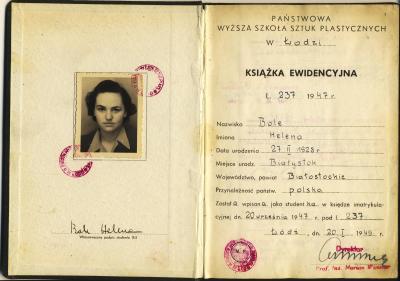

Helena Bohle-Szacki. Fashion – Art – Memories

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Helena Bohle-Szacki, 2005

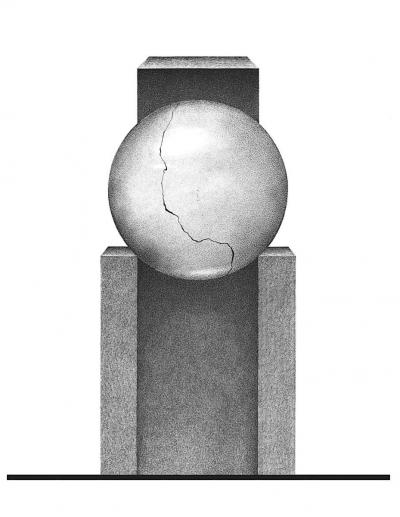

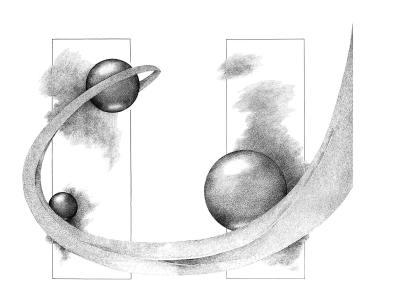

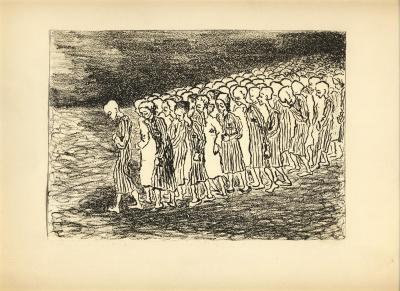

Having studied with the famous advocate of constructivism Władysław Strzemiński, whom she particularly admired, the prospective fashion designer was inspired by him. “Like Strzemiński, she considered art to be closely linked to industrial production and transferred painting ideas to textiles. She believed that fashion was a kind of art that serves everyday life and is created within a network of all artistic areas”[5], wrote the fashion journalist, Marcin Różyc and quoted Bohle-Szacki‘s reflections: “One of the most important questions when designing clothes is to fall back on and draw on purely artistic problems, such as contrasting forms, differentiating the surface structure, and taking account of the colour composition”. It is therefore no surprise that some of the fabric patterns in her designs appear to be taken from a unistic picture by Strzemiński (ill. 4). Later she incorporated distinctive neoplasticism (which Strzemiński also cherished) into fashion, as evidenced by a summer collection from the Leda fashion house in 1966. (ill. 5, 6) And nonetheless: throughout her life Helena Bohle-Szacki was never given the recognition she deserved. It was not until 2017 that the aforementioned journalist and art historian Marcin Różyc rediscovered her achievement. He now analyses and propagates the special status of the once-forgotten fashion designer.

After leaving Poland in 1968, she was to see for herself that the huge success of her fashion show in West Berlin was primarily of political significance. Armed with her German passport (her father’s inheritance) Helena Bohle-Szacki started looking for work. In doing so, it became only to clear to her that she was no longer regarded as a diva of fashion from Communist Poland, but merely as an unfortunate emigrant from the Eastern bloc who had chosen freedom in the West - as she told her friend the journalist Anna Hadrysiewicz many years later[6]. Now she was anxious to integrate and ready to make the most of her skills and abilities. She wrote several hundred applications, which finally brought her a job as a director at the Kittke und Sohn company, a “specialist in skirts”. It was not long before she became disillusioned.

Talking about her professional beginnings in West Berlin, she said: “The work was deadly boring. We produced skirts. For example, I was given a pattern and had to make about fifty variations: sometimes with a different bag, sometimes with a different button or clasp, etc.”[7] She made involuntary comparisons: “Taking this company as an example, I was able to observe the difference between the two economic systems for the first time. In Berlin it was all about profit with a minimal financial investment. In communist Poland, fashion was a kind of joke, an utterly unreasonable activity. Here you had to make at least twenty designs a day, there - there, a dozen a month.”[8] Creativity was not in demand, but rather “skill and taste”, as shown by her job reference from the “skirt specialist”.

Was it also this disappointment that inspired her to distinguish herself as an artist? She put up with the assembly line work with skirts for almost six months. After that she taught at several adult education centres where she lectured on fashion and interior design, until she finally found a position as a lecturer in graphics and visual communication at the vocational school of the Berlin Lette Association.[9] Now she was materially secure, had more time to herself, and the yearning to express herself as a free artist became all the more urgent.

[5] Marcin Różyc, Teoria mody, in: Helena Bohle-Szacka. Lilka. Mosty / Die Brücken. ed. M. Różyc, Białystok 2017, pp. 65–73.

[6] Anna Hadrysiewicz, Rozdział berliński, in: Helena Bohle-Szacka. Lilka. Mosty / Die Brücken, ed. M. Różyc, Białystok 2017, pp. 219–236.

[7] Anna Hadrysiewicz, at the specified location.

[8] Ibid.

[9] For the event to mark her 90th birthday on 28.2.2018 in the Topography of Terror, a group of students from the “Lette-Verein” prepared some sketches for the poster; see ill. 7.