Helena Bohle-Szacki. Fashion – Art – Memories

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Helena Bohle-Szacki, 2005

Memories

True, Helena Bohle-Szacki took part in a major survey in 2005[19], when she allowed herself to be interviewed on several occasions and appeared in public. But she never regarded her role as a victim to fundamentally shape her identity. Indeed she always kept her experiences at a distance, as well as investing them with a certain sense of humour, for she never dwelt on the horrors she had experienced. For decades she felt neither the need, nor probably had the strength, to share her dramatic experiences with the world around her. She never concealed them, but it was not a special topic, nor the focal point of her existence. This was to change gradually over the years when she consciously took on the role of a contemporary witness after the deterioration in her eyesight (a late consequence of her time in the camp) finally put a stop to her active artistic life. However, the most important reason for her to bear witness to the horrors she had experienced was her obligation to the victims who no longer lived and, at the same time, to posterity.

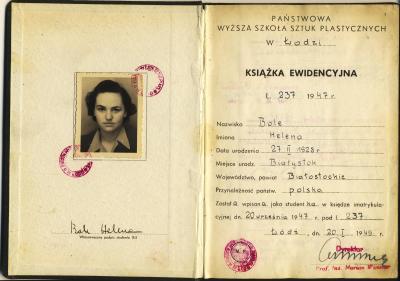

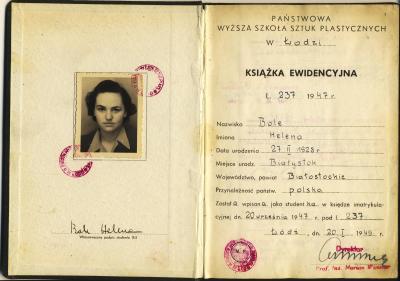

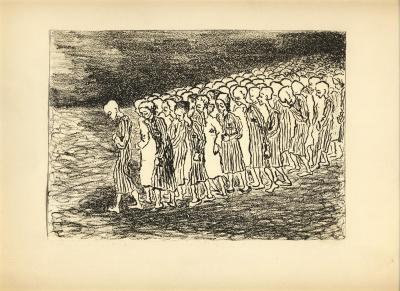

Her path in life was determined by the history of Poland and Europe in the 20th century. Born in 1928 in Polish Białystok, Helena, whose father was of German and mother of Jewish descent, experienced threats, fear and loss in wartime. Her mother was forced to live in hiding, her father daringly helped the fugitives from the Białystok ghetto, and her Jewish half-sister was arrested and murdered in the street. She herself was arrested in spring 1944, and after a few weeks in prison was transferred to the Ravensbrück concentration camp before being transported to Helmbrechts, a subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Upper Franconia. Hunger and violence, humiliation and dehumanisation were part of everyday life in the camp world. There were not many ways to survive and resist, and these required courage and strength. Helena Bohle-Szacki found them in the form of a friendship, but also in her latent ability to draw. She began making small drawings in the small subcamp, which was set up specifically to guarantee a sufficient work force for the local armaments factory. Her images were mainly those of saints with transfigured, beautiful faces, which were intended to give comfort and hope to her oppressed fellow prisoners. (ill. 25) Personally, this was probably the initial impulse for her later work.

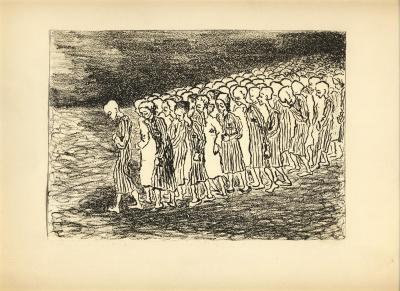

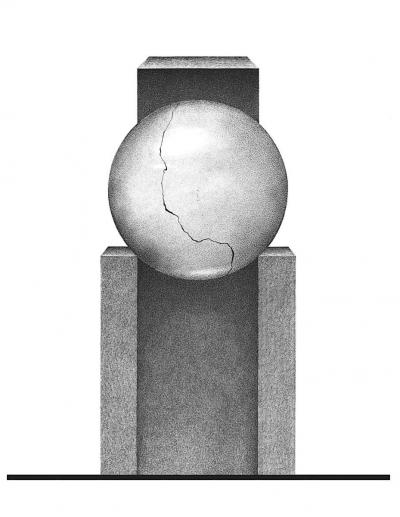

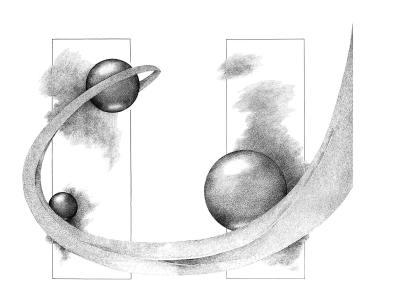

After a horrific death march at the end of the war the women were liberated and the 17-year-old Helena, emaciated and weakened, managed, not without difficulty, to return to her family in Poland. Their home in Białystok no longer existed and they were forced to rebuild their life in Lodz from scratch. Although she was afflicted by several illnesses Helena was able to start and complete her graphic studies. Only once did she address the camp world artistically: when she made some drawings to illustrate the stories of Tadeusz Borowski. (ill. 26, 27) Katarzyna Siwerska writes “The charcoal drawings on cardboard were never used, but they do have a style of their own that is clearly different from the rest of her work. Nameless, dehumanised prisoners without individual faces were contoured with a restless, vibrating line. This chaotic layering of images and memories elicits an inconceivable fear.”[20] After this one episode, for decades her experiences in the camp were no longer an issue for her – in art as well as in life.

Her late, reflective narrative aimed to bring to light the inhumanity of the National Socialist system. She said: “Today I can say that it is good to have experienced it. Everything was on the brink of life and death, but I‘m alive. I have learned a lot from that. I know for sure that it is unacceptable to put a person in extreme situations. I managed to stand firm, but I saw wonderful people collapse. That was the perfidy of the camp structure. Often people had only one choice: between viciousness and death. And then very few chose death. But they were not to blame, it was the system that destroyed people. The camp forced them to make inhuman choices.”[21]

Her recollections also shaped the feeling of being different from her very childhood onwards, since she was not a part of the Catholic majority in the student community. This feeling continued until she moved abroad. Perhaps this is precisely why she was unconditionally open to all things different and her home became a refuge for emigrants, artists and unorthodox people of all nationalities. Although she clearly felt she was a part of Polish culture, she resisted any national attributions.

A slim illustrated book “Spuren, Schatten” (Traces, Shadows), published by Helena Bohle-Szacki, constitutes a kind of bridge between memory and art in her life. The short jottings that accompany her paintings provide insight into her thoughts. She writes: “In the middle of the night I wake up bathed in sweat, terrified, my own scream wakes me, I peer into the darkness, listen to the sounds in the old house and at the same time I so much wish that the spirits would come alive again”.[22] A few pages later, we read: “How I long to reach a state of calm without having given up”[23] I presume that she achieved this state.

Helena Bohle-Szacki‘s importance cannot be reduced to one area of her work, it is based entirely on the multi-layered complexity of her life. Thus Helena, nicknamed Lilka, lives on in the memory of her fellow humans, and is to be preserved for posterity: as an extraordinary, life-affirming woman whose fate was marked by history, fashion and art. It is important to emphasise one factor that had a particularly strong influence on her personality: she had the rare talent of being able to give other people generous gifts of human warmth, friendliness, attention and, last but not least, she was always willing to help.

Ewa Czerwiakowski, May 2018

Here you can find the article on Helena Bohle-Szacki in the Atlas of Places of Remembrance.

[19] As part of the international survey led by Alexander von Plato, almost 600 interviews were conducted with former forced labourers and concentration camp prisoners from 26 countries. From this material the online archive was created, in which the interview with Helena Bohle-Szacki can also be viewed; see: https://zwangsarbeit-archiv.de/archiv

[20] Katarzyna Siwerska, at the specified location.

[21] In conversation with the author, Berlin, 31. January 1999.

[22] Helena Bohle-Szacki, Spuren, Schatten. Zeichnungen und Aufzeichnungen, Berlin 2003.

[23] Ibid.