Changes in the Ocean. On the Art of Agata Madejska

Mediathek Sorted

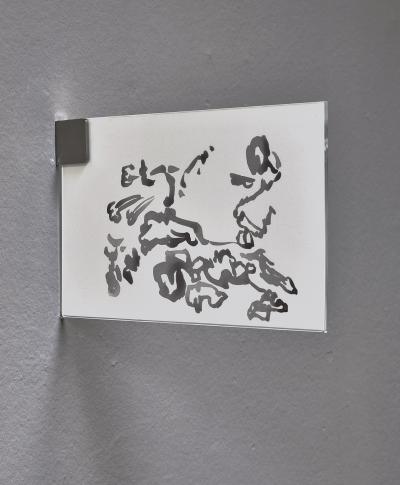

The symmetry between the tensions of the times we live in, the painful fragmentariness we experience every time we refresh what is so fittingly called the “wall,” on the one hand, and the ruptures of political space, on which the artist’s investigations are focused, on the other, is aptly reflected by the Tender Offer series (2017). Since mid-twentieth century, the boundaries of the Square Mile, as the City of London is sometimes called, have been guarded by dragon statues, symbolizing the district’s autonomy and significance.

But Madejska doesn’t watch them as a tourist. She reads them as signs, hence her particular perspective, focused on emphasizing the dragons’ prominent testicles. An exposition reminiscent of Mapplethorpe, but, surprisingly, devoid of an erotic charge – unless, of course, eroticism is accompanied by violence and domination. Then the emotional charge is worthy of the mythical predator, bespeaking of the advantage enjoyed by the men who control the financial markets.

The adopted point of view – arrested and, due to the works’ format and strong contrasts, extremely physical – is another example of how Madejska measures space. For most people craning their necks to look at the City dragons, this approach is transparent and unrecordable in the very act of looking. Here, it is elevated to the status of the only available image.

Mapped using dragons – border guards – the space of Europe’s financial centre is a place where, as Anna Gritz describes it,[5] the invisible power of money holds sway. Though mostly virtual today (something that Tolkien’s Smaug would hardly be able to put up with), it can impact on the area’s landscape in a manner worthy of urban legends. With its extensive solar shading, the glass skyscraper at 20 Fenchurch Street, nicknamed the “Walkie Talkie” because of its distinctive, top-heavy outward-bulging form, acts as a concave mirror, producing a solar glare able to melt the bodywork of cars parked in the street below.

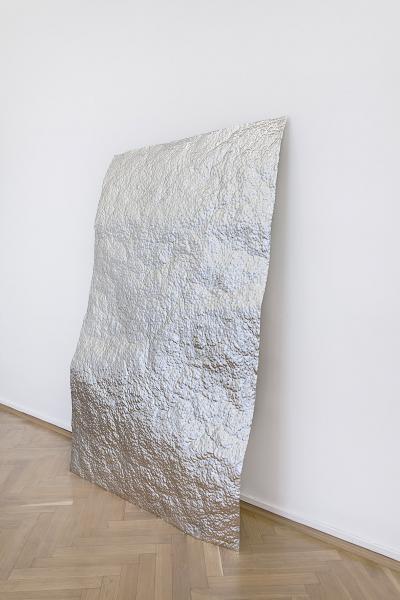

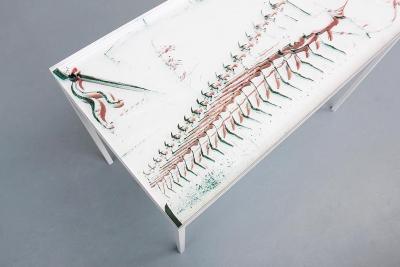

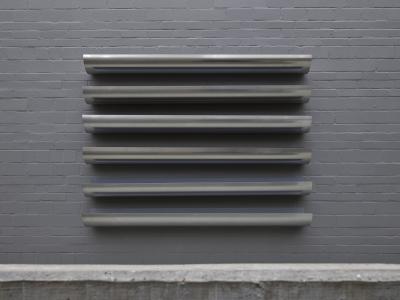

For Madejska, such an event is yet another rupture, a detail she can work with. Thanks to her alchemical flair, she creates the Technocomplex works,[6] which are a cross between photography and sculpture. The combination of photosensitive emulsion and a melted tin surface, which seems to have been deformed by a brutal (draconic?) force, yields abstract, active relief sculptures. They look like something brought out of a steel mill, hard and heavy, but at the same time, characteristically for Madejska, they can still be fluid, delicate patches.

Technocomplex is an artefact derived straight from a changing space. Firstly, globalization has changed the way money functions, secondly, digitalization (more streams of magma) has contributed to its deformation as an equivalent of labour and time, and thirdly – dragons have awakened. With the upcoming Brexit they will delimit anew the boundaries of the space they guard. The only is question is – guard against whom?

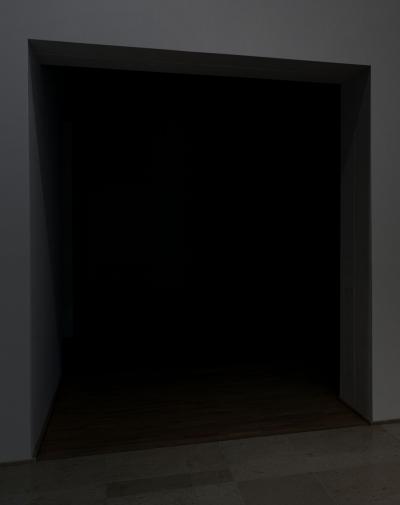

On the one hand, Agata Madejska is someone who explores gaps, moments of change pressure, the imperfections of political space which mean that it’s constantly alive, undergoing changes under the impact of successive human pressures and conflicts distributed in time,[7] while, on the other hand, she makes generalizations and attempts to go beyond the fragmentary here and now. This going in both directions of the scale is a kind of dialectical movement. A juxtaposition of the two ends produces a new image, the in-between, “proceeding” image, often in greyscale. The domination of this (non)colour seems to be a result of two key factors. The first of those is photography itself with its light-measuring system, which reduces the world to an eighteen-percent grey card. It finds itself exactly halfway between pure white and black. This system allows the artist to reduce, to become detached from redundant details, construed as present moments. The second source for this chromatic muteness is a focus on modality itself – various colours and various events can hide in grey.

It is a grey in which nothing is lost, but only morphs into something else. The ocean keeps working and reworking, proposing new forms, which, when observed long enough, yield the first generalizations, even if annotations remain inevitable.

Availing herself of the photographic metaphor, the artist stretches shutter speed infinitely, causing details to blur and colours to merge. Lest this be a mere assertion, let us return to the large-format textiles in the exhibition at the Jewish Historical Institute, or the work, also shown there, titled Every City Has Its Echo (2017), which is a greyscale take on an architectural detail of the Blue Tower, a skyscraper built on the site of the Nazi-demolished Great Synagogue of Warsaw. All that is redundant, that is perhaps bound up with restless ego, gets cut off here. A similar thing happens with the reception of the work 25-36 (2010), which portrays the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France, dedicated to the memory of Canadian soldiers killed in the First World War. Featured in the famous exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography (2014) at Tate Modern, it addressed, like many other works presented there, the uneasy relationship between the memory of an event and passing time. Like the jungle, the latter can devour the most robust constructions unless you work on preserving their status quo. That’s why the memorial is veiled by thick fog in the image, only its contours showing.[8]

[5] Anna Gritz, Ballsy, published on the occasion of the exhibition Technocomplex, http://www.madejska.eu/images/Ballsy_PDF_web.pdf.

[6] Originally presented with Tender Offer in the exhibition Technocomplex, Parrotta Contemporary Art, Stuttgart, 2017.

[7] In this, she has been informed by The Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits, a book by Bernard Mandeville. This Enlightenment-era satire on English society uses the metaphor of the beehive to describe a state that subjects itself to the rigour of perfect virtue, forsaking laziness, crime, pursuit of material goods. Those unwilling or unable to obey these rigid rules cannot be its citizens. Mandeville describes how this rigour leads to an atrophy of state and society. For the English philosopher, human imperfections are also imperfections of the system, and it is thanks to them, he argues, that the state and society can improve themselves and learn to coexist better. Human vice turns out to be the state’s vital force.

[8] The artist’s approach reminds one not only of the explorers of Solaris in Stanisław Lem’s novel, but also of Jed Martin in Michel Houellebecq’s The Map and the Territory, especially for its tangible dose of scepticism. Houellebecq’s character too liked to watch how things endure and how time works on them, often extracting an abstract essence.