Changes in the Ocean. On the Art of Agata Madejska

Mediathek Sorted

At this point, it is worth dwelling on a certain discovery that can accompany the experience of Agata Madejska’s works. It is present in the works commissioned by the Jewish Historical Institute for the exhibition Place. 3/5 Tłomackie Street (2017), where the artist explored the complex history of the building that houses the institution,[3] in works comprising the series Tender Offer (2017), which dealt with the City of London, in the 2011 photo-essay for Museum Folkwang, Temporary or Permanent, or finally in the above-mentioned works De Beers, London Stock Exchange, and The Economist. All these touch upon the subject of architecture, which in itself shows the consequences of the strategy she has adopted. In this hard to define political space, the artist maps its efflorescences and bulges. She operates similarly to the early solarists, focusing on that which demonstrates and confirms the activity of this complex structure.

But this in itself doesn’t constitute a discovery yet – it is only the way Madejska connects architecture with photography that does so. Whereas the photographic medium has historically been viewed as closely related to painting, Madejska vividly demonstrates the camera’s congruity with the solid figure and with space. She does so in a special way, one that awards priority in experiencing and thinking to the users of those structures. The artist situates them within the changing political hyperspace as if trying to bring out the intersecting vectors of interests. In those attempts, she follows details, irregularities, rifts, as if – in the spirit of Mildred and Edward Hall – she was measuring the different cubages with her own body. As Madejska mentions in her correspondence with Johanna Jaeger on the occasion of their joint exhibition,[4] her reception of space is independent of the eyes: she perceives the action field with her whole body, rebelling, in a way, against sight-centrism.

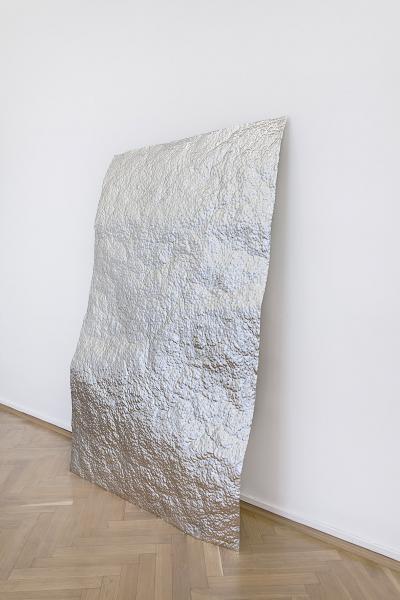

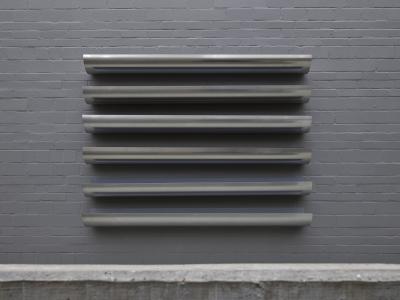

What Agata Madejska finally manages to elicit from this measuring is not so much post-memory itself as a visualization of the process of its accumulation. Examples include installations combining photosensitivity with various non-standard media, such as concrete cylinders (For Now (Folly), 2015), smooth sheets of mirror-like material (From Now On (Folly), 2014), or loosely hanging fabrics slowly reacting to light entering the room (Near Here, Not Here, Come Here, Over Here, Right Here, Here We Are, 2017). Instead of seeking to visualize a figurative record, create an index, or cite a historical fact, they allow the spectator to immerse themselves, if only for a while, in space as both magma and form. Madejska’s works are like samples here, collected from the oldest of rivers, which continues to flow in its bed.

It is also possible that the artist has at least one more reason to connect photography so emphatically with architecture. For a medium that has been described as a prosthesis of memory, building can have a similar implication. For centuries, right until the totalitarian experiences of the twentieth century, it was perceived as something more permanent than human life, and it was in architecture that the vicissitudes, functions, and traces of changes in the political space whose horizon it filled were deposited. Both these materials race against time, both into the past, which is defined by ruins, old plans, historical buildings, and photographs bound in a sentimental embrace with them, and towards the future, to avoid falling into oblivion. When buildings are demolished, perhaps at least photographs will remain?

It is also worth noting that Madejska with her practice can hardly be classified as a single-medium artist, even if photography suits her well. In one of her letters to Johanna Jaeger, she talks about how painting was her earlier experience; she discovered photography for herself only during her studies in Essen, and it is the medium’s imperfection that captivates her. The crevices hat she seeks to explore in her work originate precisely in the dubious perfection of the match between the intention to capture something and the actual representation. The difference between the initial condition and the final outcome feeds the artist’s sceptical attitude, divesting the medium itself of finality, of the power to name and indicate. Those are but approximations and modalities.

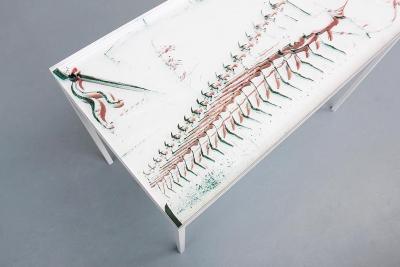

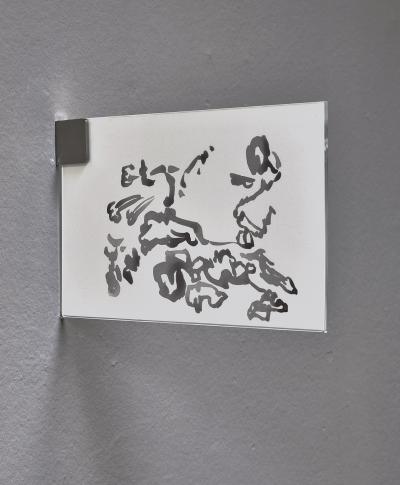

The first full embodiment of this approach is the work Factum (2014), consisting of sixteen small tables with abstract, almost stereographic images printed on layers of plexiglass. These hybrids, combining photography, installation, and sculpture, are a study of the extraordinary space that is the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park, Berlin. Its uniqueness consists in preserving in stone the mirror image that comprises the layout. The central area of the memorial is lined symmetrically on both sides by sixteen sarcophagi holding the ashes of Soviet soldiers killed in the Battle of Berlin. The sarcophagi are decorated with relief carvings of military scenes and quotations from Joseph Stalin; they can be considered as screens, or stage sets, very clearly indicating the intended viewing points. On one side, the quotations are in the original Russian; opposite are their German translations.

Forms that were meant to be identical are from the outset burdened with human error and the limitations of translation. For Madejska, this monumental reflection/representation is precisely the space to be explored. Presented on the tables are superimposed high-contrast juxtapositions of the clefts in the mirror-image figures that aren’t identical. This resembles the effect achieved with elliptical mirrors, which delay reflection, with the difference that in Factum that which the spectator receives doesn’t exist beyond the created surface of the image. The artist for the first time succeeds at capturing something between one state of matter and another.

Offering a fascinating insight into her approach to photographic material, the work is also interesting because of the very space of the memorial. After all, it is a place of commemoration, one that through its semantics reveals the history of a conflict, and the gradual loss of understanding for it, visualized by Madejska in the discrepancy of the layers, is the very work of time on this in-between space that changes, fades away, and becomes something else. This is an exposition of the potential of misunderstandings, of a disappearance of connectives, that is inherent to post-memory. At the same time, it is an ironic image of the insubordination of inanimate objects that, though designed to “remember,” can easily get out of hand.

[4] Kunstraum Griffelkunst, Hamburg, 2016.