Changes in the Ocean. On the Art of Agata Madejska

Mediathek Sorted

“Due to these fluctuations in gravity, the orbit is either flattened or distended and the elements of life, if they appear, are inevitably destroyed, either by intense heat or an extreme drop in temperature. These changes take place at intervals estimated in millions of years – very short intervals, that is, according to the laws of astronomy and biology (evolution takes hundreds of millions of years, if not a billion).”[1]

In this world, scattered into small fragments, in which individual histories begin and last only in the present, it is increasingly difficult to remember and look for traits of wholeness. This is actually self-contradictory and untenably fruitless. Any attempt to go beyond the short perspective of a single life is brought down by the weight of doubts and tangled plots – the possible reinterpretations and borrowings. Simulacra fill albums, memories, words remain multi-level metaphors, and the certainty of facts boils down to mediality and short use-by dates.

In this world, in which gravity is still de rigueur, even concrete, stone, and steel can’t be sure of their permanence. Buildings collapse, erased from panoramas, immediately replaced by new ones; statues are knocked down, moved elsewhere, sometimes covered or remade. With all the elasticity and stretchability of the new reality, it can very decisively and aggressively impact on until recently solid man-made objects.

The space that is being so dynamically transformed has long ceased being called natural, even where it was originally green. It has long become human domain. A whole arsenal of technological means supporting these transformations only affirms, like an old torture, this dominion. It is special insofar that in its scale that getting beyond it is impossible. It is total, even though little, or only as much as the rampant entropy allows, remains of the Enlightenment ideals of control, learning, and perfection. Even the panoptic vision is turning a blind eye.

This hyperspace requires, of course, a name – we can call it human reality. But this designation misses the dynamic that so determines today’s dispersion and anxiety, that allows us to see the growing entropy as something that has a source. So this would be a force that affects everyone and everything. It may be politics – construed broadly as a sum total of the activities that organize human life, confining it within a grid of intersecting interests and making it possible to abstract individual existence into mass and generalization. Explaining its scale and omnipresent force is a basic mechanism of human action – the need to organize into groups in order to increase the chances of survival.

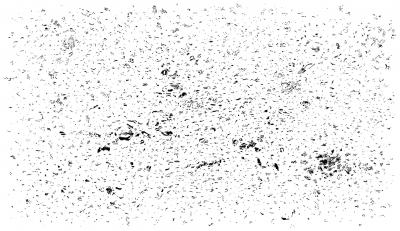

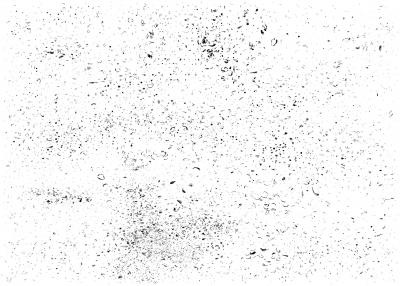

But this isn’t a uniform space, fully planned and developed according to standard. In many places it seems to be bursting open, building anew, cracking at the bends. For Agata Madejska, this living ocean is a subject of ongoing artistic investigations. The cracks, ruptures, and fluctuations are precisely what rivets her attention. It is them that are symmetrically juxtaposed with all the anxieties that haunt the present. An excellent example of this practice is an untitled series of large-format photographs representing almost organic, cellular black-and-white patches. The first impression is of magma, of a difficulty to find one’s bearings in the here and now. Only upon closer inspection, as the gaze becomes more pensive, do shapes, patterns, and details emerge from the magma. The black-and-white dots gain value as shells appear in them, prehistoric organisms trapped in stone. A moment later the works’ titles – De Beers (2017), London Stock Exchange (2017), The Economist (2015) – begin to tell another part of the story. These minimalistic works are collages of photographs of the limestone façades of buildings such as the London Stock Exchange or the headquarters of the world’s leading diamond company. Each print is unique, produced as a montage of multiple images, thus representing the time-stretched modality contained in the stone deposits.

Madejska has very deliberately chosen buildings that constitute intersection points, dialectical areas of power, in the political space.[2] She maps them however below the horizon of current public debate. In this archaeological gaze – for it is one that leads towards the foundations – she asks about their permanence. The visible fossils, which had been subject to successive transformations under the pressure of time, have become building material for human institutions of power. With this exhibition, Madejska’s attitude towards the space explored and its order, an attitude radiating throughout her work, is revealed. She strips it of the pathos of grandeur and the daring, post-Enlightenment challenge posed to an unknown future, assuming that the space that she observes from inside will too be subject to change, to a process of weathering away. For this reason, also the certainty that accompanies the architecture of power is vulnerable to erosion. Even those institutions must remember that they are founded on the death of their predecessors.

At this point, it is worth dwelling on a certain discovery that can accompany the experience of Agata Madejska’s works. It is present in the works commissioned by the Jewish Historical Institute for the exhibition Place. 3/5 Tłomackie Street (2017), where the artist explored the complex history of the building that houses the institution,[3] in works comprising the series Tender Offer (2017), which dealt with the City of London, in the 2011 photo-essay for Museum Folkwang, Temporary or Permanent, or finally in the above-mentioned works De Beers, London Stock Exchange, and The Economist. All these touch upon the subject of architecture, which in itself shows the consequences of the strategy she has adopted. In this hard to define political space, the artist maps its efflorescences and bulges. She operates similarly to the early solarists, focusing on that which demonstrates and confirms the activity of this complex structure.

But this in itself doesn’t constitute a discovery yet – it is only the way Madejska connects architecture with photography that does so. Whereas the photographic medium has historically been viewed as closely related to painting, Madejska vividly demonstrates the camera’s congruity with the solid figure and with space. She does so in a special way, one that awards priority in experiencing and thinking to the users of those structures. The artist situates them within the changing political hyperspace as if trying to bring out the intersecting vectors of interests. In those attempts, she follows details, irregularities, rifts, as if – in the spirit of Mildred and Edward Hall – she was measuring the different cubages with her own body. As Madejska mentions in her correspondence with Johanna Jaeger on the occasion of their joint exhibition,[4] her reception of space is independent of the eyes: she perceives the action field with her whole body, rebelling, in a way, against sight-centrism.

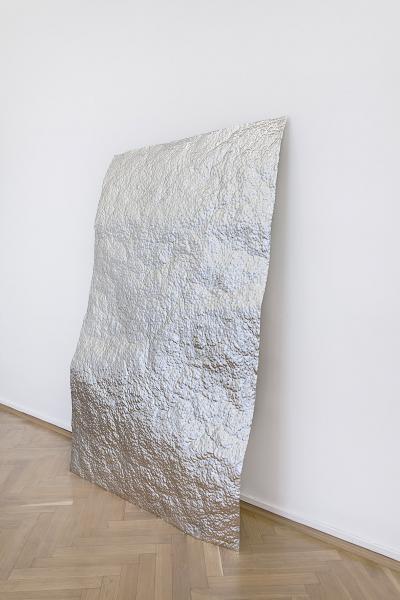

What Agata Madejska finally manages to elicit from this measuring is not so much post-memory itself as a visualization of the process of its accumulation. Examples include installations combining photosensitivity with various non-standard media, such as concrete cylinders (For Now (Folly), 2015), smooth sheets of mirror-like material (From Now On (Folly), 2014), or loosely hanging fabrics slowly reacting to light entering the room (Near Here, Not Here, Come Here, Over Here, Right Here, Here We Are, 2017). Instead of seeking to visualize a figurative record, create an index, or cite a historical fact, they allow the spectator to immerse themselves, if only for a while, in space as both magma and form. Madejska’s works are like samples here, collected from the oldest of rivers, which continues to flow in its bed.

It is also possible that the artist has at least one more reason to connect photography so emphatically with architecture. For a medium that has been described as a prosthesis of memory, building can have a similar implication. For centuries, right until the totalitarian experiences of the twentieth century, it was perceived as something more permanent than human life, and it was in architecture that the vicissitudes, functions, and traces of changes in the political space whose horizon it filled were deposited. Both these materials race against time, both into the past, which is defined by ruins, old plans, historical buildings, and photographs bound in a sentimental embrace with them, and towards the future, to avoid falling into oblivion. When buildings are demolished, perhaps at least photographs will remain?

It is also worth noting that Madejska with her practice can hardly be classified as a single-medium artist, even if photography suits her well. In one of her letters to Johanna Jaeger, she talks about how painting was her earlier experience; she discovered photography for herself only during her studies in Essen, and it is the medium’s imperfection that captivates her. The crevices hat she seeks to explore in her work originate precisely in the dubious perfection of the match between the intention to capture something and the actual representation. The difference between the initial condition and the final outcome feeds the artist’s sceptical attitude, divesting the medium itself of finality, of the power to name and indicate. Those are but approximations and modalities.

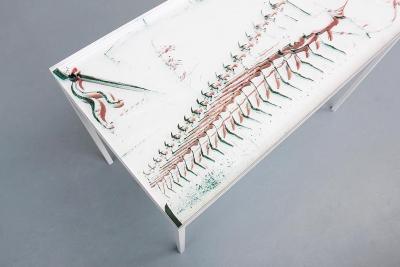

The first full embodiment of this approach is the work Factum (2014), consisting of sixteen small tables with abstract, almost stereographic images printed on layers of plexiglass. These hybrids, combining photography, installation, and sculpture, are a study of the extraordinary space that is the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park, Berlin. Its uniqueness consists in preserving in stone the mirror image that comprises the layout. The central area of the memorial is lined symmetrically on both sides by sixteen sarcophagi holding the ashes of Soviet soldiers killed in the Battle of Berlin. The sarcophagi are decorated with relief carvings of military scenes and quotations from Joseph Stalin; they can be considered as screens, or stage sets, very clearly indicating the intended viewing points. On one side, the quotations are in the original Russian; opposite are their German translations.

Forms that were meant to be identical are from the outset burdened with human error and the limitations of translation. For Madejska, this monumental reflection/representation is precisely the space to be explored. Presented on the tables are superimposed high-contrast juxtapositions of the clefts in the mirror-image figures that aren’t identical. This resembles the effect achieved with elliptical mirrors, which delay reflection, with the difference that in Factum that which the spectator receives doesn’t exist beyond the created surface of the image. The artist for the first time succeeds at capturing something between one state of matter and another.

Offering a fascinating insight into her approach to photographic material, the work is also interesting because of the very space of the memorial. After all, it is a place of commemoration, one that through its semantics reveals the history of a conflict, and the gradual loss of understanding for it, visualized by Madejska in the discrepancy of the layers, is the very work of time on this in-between space that changes, fades away, and becomes something else. This is an exposition of the potential of misunderstandings, of a disappearance of connectives, that is inherent to post-memory. At the same time, it is an ironic image of the insubordination of inanimate objects that, though designed to “remember,” can easily get out of hand.

The symmetry between the tensions of the times we live in, the painful fragmentariness we experience every time we refresh what is so fittingly called the “wall,” on the one hand, and the ruptures of political space, on which the artist’s investigations are focused, on the other, is aptly reflected by the Tender Offer series (2017). Since mid-twentieth century, the boundaries of the Square Mile, as the City of London is sometimes called, have been guarded by dragon statues, symbolizing the district’s autonomy and significance.

But Madejska doesn’t watch them as a tourist. She reads them as signs, hence her particular perspective, focused on emphasizing the dragons’ prominent testicles. An exposition reminiscent of Mapplethorpe, but, surprisingly, devoid of an erotic charge – unless, of course, eroticism is accompanied by violence and domination. Then the emotional charge is worthy of the mythical predator, bespeaking of the advantage enjoyed by the men who control the financial markets.

The adopted point of view – arrested and, due to the works’ format and strong contrasts, extremely physical – is another example of how Madejska measures space. For most people craning their necks to look at the City dragons, this approach is transparent and unrecordable in the very act of looking. Here, it is elevated to the status of the only available image.

Mapped using dragons – border guards – the space of Europe’s financial centre is a place where, as Anna Gritz describes it,[5] the invisible power of money holds sway. Though mostly virtual today (something that Tolkien’s Smaug would hardly be able to put up with), it can impact on the area’s landscape in a manner worthy of urban legends. With its extensive solar shading, the glass skyscraper at 20 Fenchurch Street, nicknamed the “Walkie Talkie” because of its distinctive, top-heavy outward-bulging form, acts as a concave mirror, producing a solar glare able to melt the bodywork of cars parked in the street below.

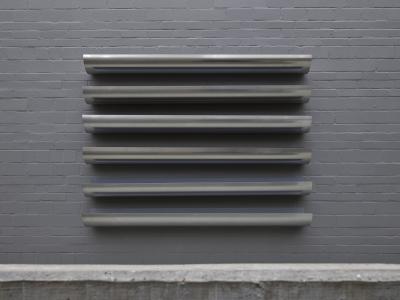

For Madejska, such an event is yet another rupture, a detail she can work with. Thanks to her alchemical flair, she creates the Technocomplex works,[6] which are a cross between photography and sculpture. The combination of photosensitive emulsion and a melted tin surface, which seems to have been deformed by a brutal (draconic?) force, yields abstract, active relief sculptures. They look like something brought out of a steel mill, hard and heavy, but at the same time, characteristically for Madejska, they can still be fluid, delicate patches.

Technocomplex is an artefact derived straight from a changing space. Firstly, globalization has changed the way money functions, secondly, digitalization (more streams of magma) has contributed to its deformation as an equivalent of labour and time, and thirdly – dragons have awakened. With the upcoming Brexit they will delimit anew the boundaries of the space they guard. The only is question is – guard against whom?

On the one hand, Agata Madejska is someone who explores gaps, moments of change pressure, the imperfections of political space which mean that it’s constantly alive, undergoing changes under the impact of successive human pressures and conflicts distributed in time,[7] while, on the other hand, she makes generalizations and attempts to go beyond the fragmentary here and now. This going in both directions of the scale is a kind of dialectical movement. A juxtaposition of the two ends produces a new image, the in-between, “proceeding” image, often in greyscale. The domination of this (non)colour seems to be a result of two key factors. The first of those is photography itself with its light-measuring system, which reduces the world to an eighteen-percent grey card. It finds itself exactly halfway between pure white and black. This system allows the artist to reduce, to become detached from redundant details, construed as present moments. The second source for this chromatic muteness is a focus on modality itself – various colours and various events can hide in grey.

It is a grey in which nothing is lost, but only morphs into something else. The ocean keeps working and reworking, proposing new forms, which, when observed long enough, yield the first generalizations, even if annotations remain inevitable.

Availing herself of the photographic metaphor, the artist stretches shutter speed infinitely, causing details to blur and colours to merge. Lest this be a mere assertion, let us return to the large-format textiles in the exhibition at the Jewish Historical Institute, or the work, also shown there, titled Every City Has Its Echo (2017), which is a greyscale take on an architectural detail of the Blue Tower, a skyscraper built on the site of the Nazi-demolished Great Synagogue of Warsaw. All that is redundant, that is perhaps bound up with restless ego, gets cut off here. A similar thing happens with the reception of the work 25-36 (2010), which portrays the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France, dedicated to the memory of Canadian soldiers killed in the First World War. Featured in the famous exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography (2014) at Tate Modern, it addressed, like many other works presented there, the uneasy relationship between the memory of an event and passing time. Like the jungle, the latter can devour the most robust constructions unless you work on preserving their status quo. That’s why the memorial is veiled by thick fog in the image, only its contours showing.[8]

For Madejska, words mean a lot. Finding the right ones is not only part of proper research, something that contemporary artists are used to, but the actual work area. One could even say that her works are a consequence of words, which form the main building blocks of political space itself.

This close relationship between word and work is evident on several levels. Firstly, in the titles themselves – they are either descriptive, lengthy, as if preparing a melody or rhythm for the spectator, e.g. Near Here, Not Here, Come Here, Over Here, Right Here, Here We Are (2017), or short, dry, as if measured off with meticulous precision, e.g. 25-36 (2010), 46-48 (2010), 81-86 (2010), 1906 (2012), which are references to the dates when particular monumental structures were built. The titles are like an introduction, setting a tone for the works’ reception, sometimes, like the first one above, providing momentum themselves, at other times showing time itself – its impact.

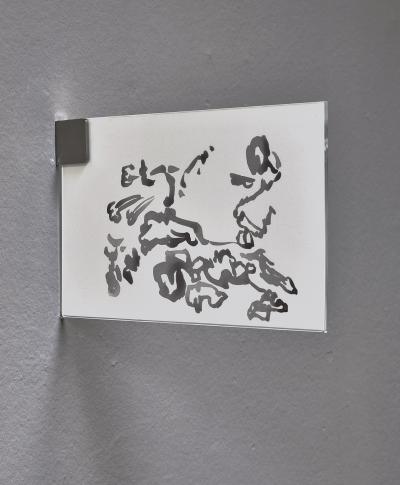

Another level of this connection is how the artist employs the means available to work with words. To observe how they shed the redundant articles, complements, momentary details. The work Mistakes Were Made (2018), where politicians’ speeches, sans the factography, are recited by professional voice actors, is an example of this practice.

Madejska manages to touch upon something unobvious here. The recordings are of State of the Union speeches and similar addresses. Through “surgical” procedures, by editing and redacting, the artist turns them into admissions of weakness, declarations of love, reflections on community. On the semantic level, these touching monologues are a kind of secular confession addressed at a loved one. In times of post-truth, one could hardly think of a more significant gesture imbuing words with emotions and values that accompany relationships of familial and romantic love.

Simultaneously with this “ballasting” of words, their political undertone bears the marks of universality and a reference to the mythical roots of the contract between the state and its citizens. Madejska recovers a word-based community from the recesses of shattered history, investing it with a new, emotional quality.

In Mistakes Were Made, this mythological community is something rough and very soft at the same time. The apparent contradiction stems from the fact of these being confessions, which, after all, are admissions of failure, sin, and weakness, made by people who are supposed to take helm and provide leadership.

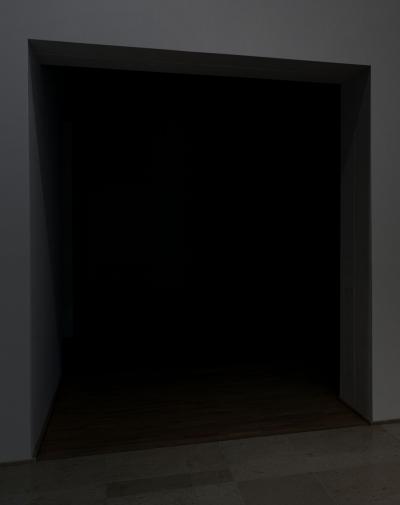

Such a tender treatment of community is like a reappraisal of the Hobbesian social contract, the main purpose of which is survival under the sovereign power of the Leviathan. In Mistakes Were Made, survival however seems to be an insufficient condition for the contract to be kept. Experienced by the spectator in the intimate space of a black tent, the moment of the admission of failure is like a promise of its rewriting to include a new postulate – investing society with agency on the same terms on which two persons can talk to each other in a committed relationship.

Agata Madejska construes politicalness first and foremost as a dynamic of human activities. It is politicalness that organizes the space of human life. The tensions and bulges of this space, which can be different in terms of organization, but its undersoil, its building material is always the same, will continue until history ends, as Fukuyama wanted to believe until recently. The artist seeks to bring out these special moments of the ocean’s activity on particular examples from the past. It is in it that she finds images, genre scenes, as it were, that allow us to better feel the power of politicalness even if not necessarily to better understand it.

Such a scene from the past is the 1918 sailors’ mutiny in Kiel, which triggered the German revolution. On the centenary of the event, in Wilhelmshaven, where the first protests erupted, Agata Madejska staged the exhibition Modified Limited Hangout.

It is the artist’s largest solo show to date, bringing together many of her practiced procedures and extraction methods. At the same time, due to its very size, the sum total of the gestures has been multiplied, yielding a dense, anxiety-streaked atmosphere. It is a psychological thriller without an obvious protagonist rather than a historical epic peopled by familiar characters. As usual, Madejska has cleared the scene of decorations, figurativeness, and simple indexation. And perhaps that’s why in the dominant greyness we won’t find the idea of the past as a simple collection of facts comprising an explanation of the mutiny – an act of resistance, of refusal to obey the Leviathan. What remains here is an energy, a tension between the awareness of the facts that the spectators bring with them to the show and the here-and-now burden of a fragmented world.

As in the earlier Tender Offer, which had a creeping Brexit as its background, so here a historical revolt seems like a kind of matrix for something new that is yet to emerge. On various levels, using previously tested tools, Madejska attempts to delineate its blurry contours. In this matrix can be found all the contemporary anxieties – populisms, post-truth, surveillance technology, growing social disparities and mistrust in institutions, atrophy of social life and so on.

That’s why the show at the Kunsthalle Wilhelmshaven features Mistakes Were Made as well as a new work, inspired by the Crystal Chain (“Gläserne Kette”), a chain letter initiated in 1919 by Bruno Taut to share views with other visionary architects on the kind of architecture that could emerge after the November Revolution. Madejska revives this utopian dialogue in the work Where Should We Turn to In Order to Arrive Where Exactly? (2018), which is the transcript of a debate between Nina Franz, Rebecca Ladewig, and Eva Wilson. The work is yet another example of the artist’s preoccupation with the word, with processes of searching for the new, of seeking consensus and support for premonitions in verbal exchanges.

Utopia and its fallacious hopes return also in another work, Voyage, Voyage (2018), which assumes the form of a carpet with geometric patterns, an allusion to a swathe of land purchased in 1848 in Texas by the radical socialist Etienne Cabet for his Icarian community. The particular shape of the plots resulted from a division entailed by a contract between the state authorities and the company selling the land. The division hindered the fledgling commune’s development and nearly led to its collapse. This work has been juxtaposed with the Technocomplex series, which remains an example of the brutality of entropy developing in designed space.

For the Wilhelmshaven show, Madejska has also prepared a work that appears to be a continuation of solaristic observations, this time conducted with the aid of mathematical formulas. Simon Says (2018) is a series inspired by the Josephus permutation,[9] a theoretical problem in combinatorial mathematics, which for the artist becomes an opportunity to reflect on the randomness of or even to predict bulges and tensions in political space, especially those related to racial or religious conflicts or lack of empathy.[10] However, as it often happens for solarists and for Madejska too, the ocean remains unperturbed here, and in this particular case, grey.

Sharing the same tonality is yet another series made for Modified Limited Hangout, titled RISE (2018). These are special works for the show, looking as if straight out of a Lem-style science-fiction laboratory – images of photochemical smog caused by the interaction of ultraviolet solar radiation with a high concentration of exhaust fumes and industrial emissions. RISE is an extreme record of the entropy materializing in present-day space, notably in big cities. In Madejska’s formulation, those are samples of changes, of factors that the Leviathan hasn’t yet responded to, perhaps hasn’t even noticed.

With RISE, Madejska crosses the boundary where the invisible filling of political space, something that affects us all, becomes a visible hyperobject. From the Factum series, where she first attempted to create a new image, she has arrived here through her alchemical technique at an absolutely unique achievement. The probes she released have revealed a new entity.

Jakub Śwircz, November 2019