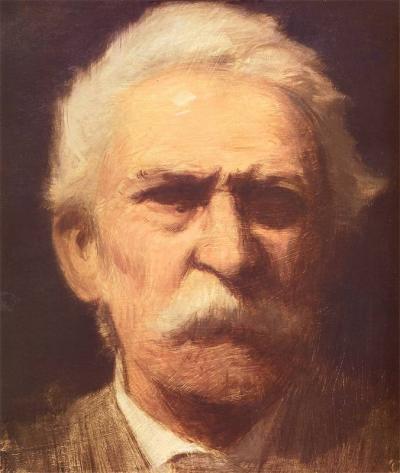

Roman Kochanowski (1857-1945) - the last “Münchener” from Poland

Mediathek Sorted

![Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [in winter] Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [in winter] - Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [im Winter], 1896, oil on paper, 102 x 29 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/6.%20koch-1_R.%20Kochanowski%2C%20Pejzaz%CC%87%20wiejski%2C%20olej%2C%20papier%2C%2029x102%20cm.jpg?itok=hOUiRVi4)

![Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [mit Weiden] Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [mit Weiden] - Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [mit Weiden], 1896, oil on paper, 17.7 x 23 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/7.%20koch-2_R.%20Kochanowski%2C%20Pejzaz%CC%87%20wiejski%2C%20olej%2C%20papier%2C%2017%2C7x23%20cm.jpg?itok=X_2aOKBz)

![Roman Kochanowski, Engelsberg [Bavaria] Roman Kochanowski, Engelsberg [Bavaria] - Roman Kochanowski, Engelsberg [Bavaria], photo, photographic paper on board, 14.5 x 19.5 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/009%20fot%201ms-s-1035-18%20view.jpg?itok=Yramc6Ij)

![Roman Kochanowski, Wieliczka [near Kraków] Roman Kochanowski, Wieliczka [near Kraków] - Roman Kochanowski, Wieliczka [near Kraków], photo, photographic paper on board, 14.5 x 19.5 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/010%20fot%20R.%20Kochanoskiego%2C%20Panorama%20Wieliczki.jpg?itok=19YPFxaN)

From 1892, Kochanowski was a member in the Watercolourists’ Club, an organisation of the Watercolourist Clubs of the Cooperative of Creative Artists in Vienna, and took part in their exhibitions, sometimes as the only Polish artist. His unassuming, small-format landscapes satisfied the tastes of the day. Occasionally, their creator was honoured; sometimes, in an exhibition report, somebody would underline the particular charm of the very personal works. The honours include the honorary second class degree, which was awarded to the artist in 1891 on the occasion of an exhibition in London, and the silver medal of the Lemberg General Regional Exhibition of 1894.

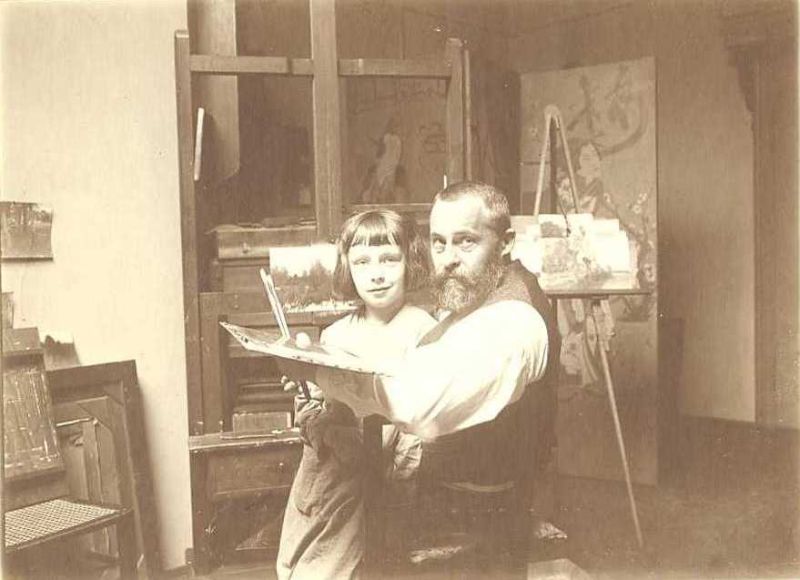

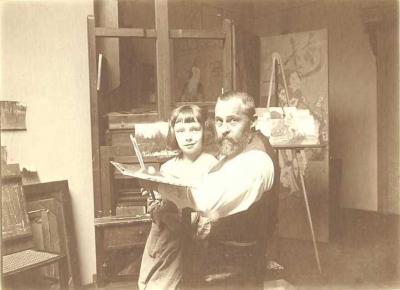

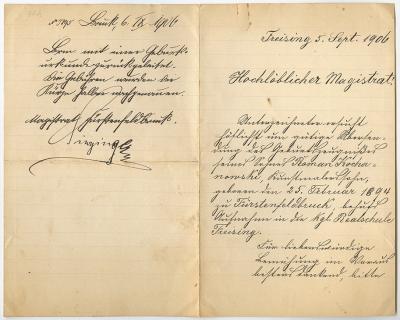

The late eighties and early nineties represented an important phase in the life of Roman Kochanowski. He had settled in Munich, formed friendships and developed fixed routines. At the same time, he was becoming more and more sceptical at the thought of returning to Poland. Spurred on by Piotr Stachiewicz and his family, he sometimes thought about moving to Kraków but the financial uncertainty of artists in Poland and the unfavourable conditions on the Polish art market led him to reject the idea. His long-term relationship with Maria, the daughter of the Bavarian entrepreneur Kaffel, culminated in their marriage in 1984. His only child, a son, Roman Junior, was born two years later.

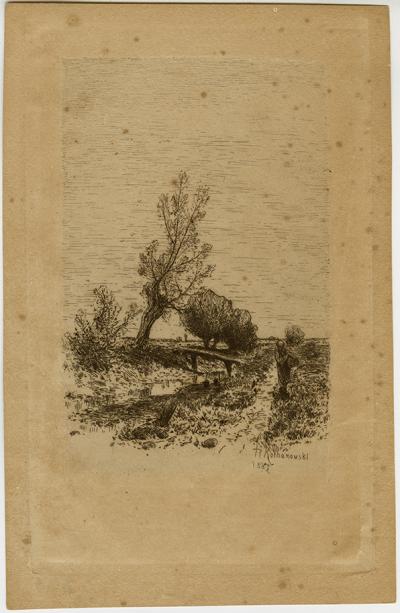

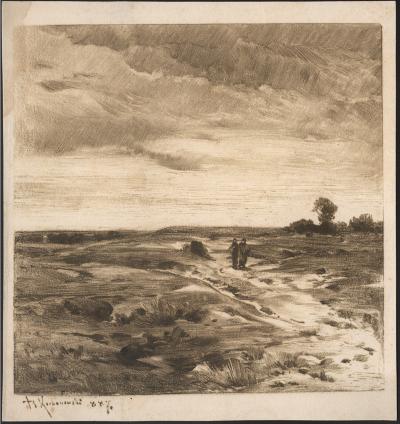

Kochanowski was able to establish himself as an artist early, during the first phase of his work. But he never felt the inner need to gain new impressions and inspirations by engaging with other cultural traditions and places. His fulfilled his ambitions and satisfied his need for emotionalism by only depicting seemingly random nature motifs. These were usually sweeping plains, the monotony of which was broken up by casually interspersed huts, sparse plantations, a wood, or a dirt track. Like the exponents of the Barbizon School, he painted groups of trees at the waterside and polder fields or he created visions within a wood. He was not interested in cityscapes or rural traditions. He brought the poor areas of Krakow to life with staffage.[11] His favourite accessories were geese and cows, but most frequently he chose a female figure which lent the compositions a warm, intimate character. The artist never tried to capture fleeting, barely perceptible changes in his landscapes dictated by the time of day, the play of the clouds or the terrain profiles; instead, what he captured on canvas were things that he considered permanent and enduring. All the components of his pictures were shown in scattered light. A low horizon and a high, cloudy sky form the space in which the person is no more than a barely perceptible speck and a somewhat insignificant part of the world.

[11] The artist even gave pictures inspired by Bavarian landscapes names that suggest that they portrayed Polish subject matters.