Roman Kochanowski (1857-1945) - the last “Münchener” from Poland

Mediathek Sorted

![Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [in winter] Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [in winter] - Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [im Winter], 1896, oil on paper, 102 x 29 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/6.%20koch-1_R.%20Kochanowski%2C%20Pejzaz%CC%87%20wiejski%2C%20olej%2C%20papier%2C%2029x102%20cm.jpg?itok=hOUiRVi4)

![Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [mit Weiden] Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [mit Weiden] - Roman Kochanowski, Dorflandschaft [mit Weiden], 1896, oil on paper, 17.7 x 23 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/7.%20koch-2_R.%20Kochanowski%2C%20Pejzaz%CC%87%20wiejski%2C%20olej%2C%20papier%2C%2017%2C7x23%20cm.jpg?itok=X_2aOKBz)

![Roman Kochanowski, Engelsberg [Bavaria] Roman Kochanowski, Engelsberg [Bavaria] - Roman Kochanowski, Engelsberg [Bavaria], photo, photographic paper on board, 14.5 x 19.5 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/009%20fot%201ms-s-1035-18%20view.jpg?itok=Yramc6Ij)

![Roman Kochanowski, Wieliczka [near Kraków] Roman Kochanowski, Wieliczka [near Kraków] - Roman Kochanowski, Wieliczka [near Kraków], photo, photographic paper on board, 14.5 x 19.5 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/010%20fot%20R.%20Kochanoskiego%2C%20Panorama%20Wieliczki.jpg?itok=19YPFxaN)

His pictures showed: “Meadows, muddy paths, game woods, thatched cottages, goose girls, grandmothers with bundles of collected brushwood. Woods, plantations, morning mists and sunsets.” [2] Hidden between mounds of musty magazines from the end of the 19th century and piles of books were all kinds of treasure chests with “Kraków smocks, ravaged by time, once white and brown, with faded, coloured collars and embroidery, Kraków belts with all kinds of brass fittings, brass buttons of former Polish regiments from the Duchy of Warsaw, from Congress Poland and perhaps also from the end of the Republic, red peaked Kraków caps, also known as Konfederatka, with lambskin edging – without peacock feathers, because they had already fallen off; and, in better condition, ladies’ coloured skirts, richly embroidered blouses, Kraków cloths in fresh colours of yesteryear.”[3] There were also letters, photos and sketch books that for years nobody had shown any interest in.

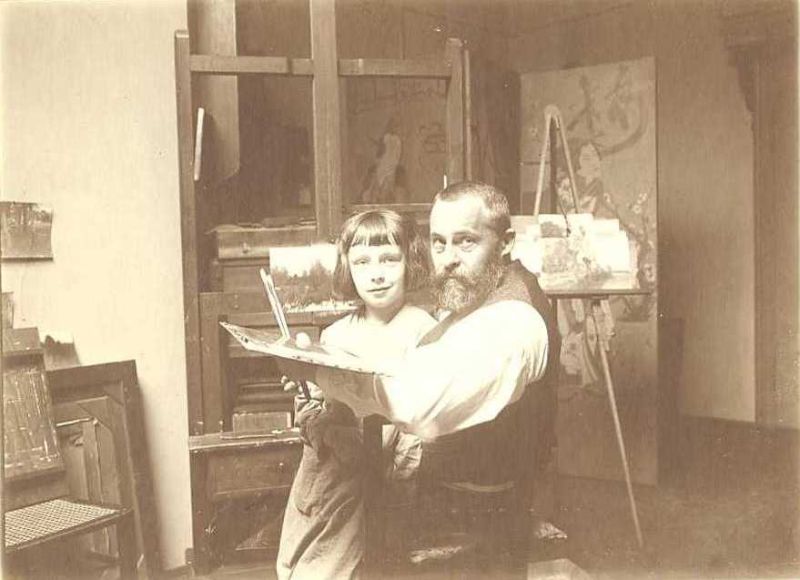

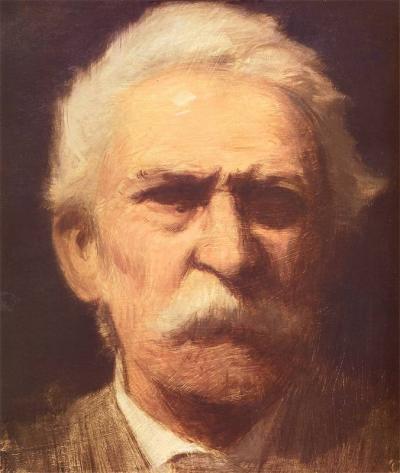

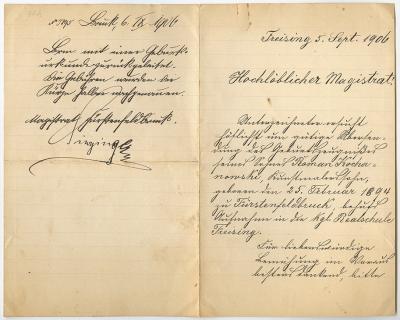

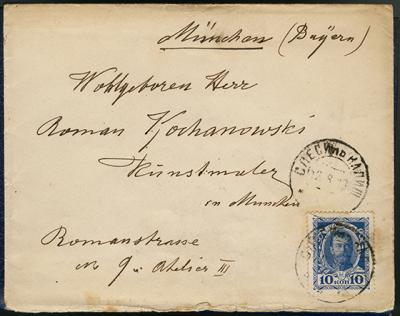

Roman Kochanowski was born on 28 February 1857 in Kraków, the son of a craftsman and property owner who was keen for his son to have an education. But when, as an adolescent, Roman chose to be an artist, his father did not stop him. In the grammar school, he had his first art lesson from Maksymilian Cercha, a man whose artistic passion was aroused by the Kraków of the time. [4] Roman then attended the School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych), where he studied under Władysław Łuszczkiewicz and Henryk Grabiński. The friendship with the former and his shared interests with the latter, a landscape painter trained in Vienna, Munich and Paris, had a positive effect on the student. Roman Kochanowski felt vindicated in his decision to be an artist and continued his training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.[5]

In 1874, he enrolled in Christian Grippenkerl’s class and in the class held by the landscape painter Eduard Lichtenfels. Financial problems in his family meant that Kochanowski’s early years of study were anything but easy. As a result, he made every effort to be independent as quickly as possible. He sold his first pieces and took part in exhibitions in Kraków, Warsaw (Warszawa) and Lemberg (Lwów; today Lwiw in the Ukraine). In 1881, after completing his studies, he decided to go to Munich. For decades, the city had attracted generations of aspiring artists. A few years after Kochanowski had settled in the Bavarian metropolis, his younger colleague Marian Trzebiński remembered their time at the Kraków art school: “time and again, some ‘Münchener’ would pop up (…) and tell us about the wonders of Munich (…). Just paint and sell. On top of that, life was fantastically cheap .”[6] The well developed art market, its high standard and the lively exhibition scene had a powerful attraction on Kochanowski as well. In Munich, he began to work for himself instead of continuing his studies. He sent his pictures to exhibitions in Vienna and Berlin and also exhibited in Munich and Poland. Then in 1888, he celebrated a win when Emperor Franz Joseph acquired his painting “Polish Winter” (Zima w Polsce)[7]. A few years later, the monarch again purchased one of his works, this time the painting “Autumn” (Jesień).[8] Kochanowski created many paintings around this theme.

In 1888, during a brief stay in Paris, the artist got to know the works of the painter Jean Baptist Corot and the works of other representatives of the Barbizon School, which, as often emphasised, had an influence on his creativity. [9] Kochanowski did not travel to any other European centres of art. But he did visit Kraków regularly and he wandered through the meadows and the moors in the countryside around Munich, which was then reproduced on his canvases, supposedly as the wetlands in Mazovia or in the Kraków region. In his memory he stored impassable areas, small towns inhabited by poor people, landscapes that were picturesque in their melancholy and inconspicuousness, and later put them into pictures.

One of the longest journeys that Roman Kochanowski undertook was a trek along the border in south-eastern Galicia. The aim of this journey was to prepare drawings of geographically and historically interesting places. Subsequently, Emperor Franz Joseph commissioned the multi-volume monography “Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy in Words and Pictures“, which contained numerous descriptions and illustrations of its regions. Roman Kochanowski and other Polish artists, such as Julian Fałat, Wojciech Kossak and Piotr Stachiewicz, created illustrations for the volume dedicated to Galicia. [10] At the time, Kochanowski had been working for some time as an illustrator and front cover designer for the society and culture magazine “Świat” (The World), which was founded in Kraków in 1888. The person largely responsible for this engagement was Piotr Stachiewicz, who was a very important person to Kochanowski and with whom he was friends and shared common ideas and interests. Reproductions of Kochanowski’s pictures also appeared in two other Polish weekly magazines, in “Biesiada Literacka” (Literary Round Table) and in “Tygodnik Ilustrowany” (Illustrated Weekly Magazine).

From 1892, Kochanowski was a member in the Watercolourists’ Club, an organisation of the Watercolourist Clubs of the Cooperative of Creative Artists in Vienna, and took part in their exhibitions, sometimes as the only Polish artist. His unassuming, small-format landscapes satisfied the tastes of the day. Occasionally, their creator was honoured; sometimes, in an exhibition report, somebody would underline the particular charm of the very personal works. The honours include the honorary second class degree, which was awarded to the artist in 1891 on the occasion of an exhibition in London, and the silver medal of the Lemberg General Regional Exhibition of 1894.

The late eighties and early nineties represented an important phase in the life of Roman Kochanowski. He had settled in Munich, formed friendships and developed fixed routines. At the same time, he was becoming more and more sceptical at the thought of returning to Poland. Spurred on by Piotr Stachiewicz and his family, he sometimes thought about moving to Kraków but the financial uncertainty of artists in Poland and the unfavourable conditions on the Polish art market led him to reject the idea. His long-term relationship with Maria, the daughter of the Bavarian entrepreneur Kaffel, culminated in their marriage in 1984. His only child, a son, Roman Junior, was born two years later.

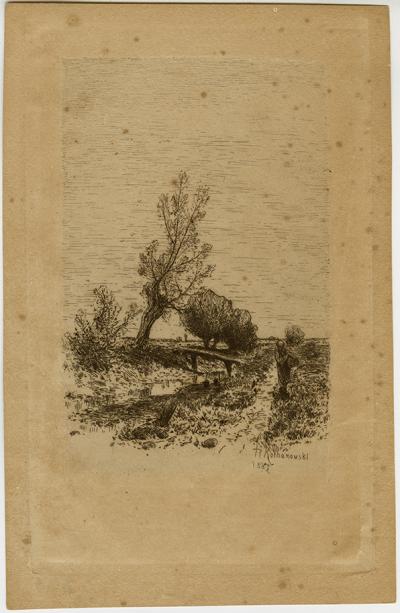

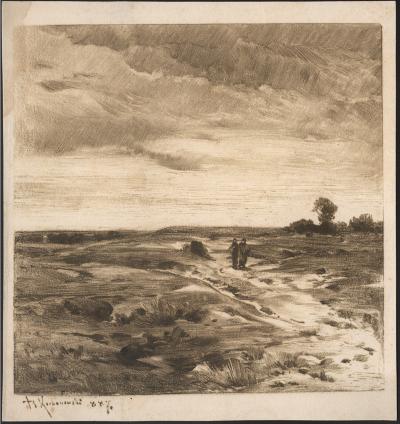

Kochanowski was able to establish himself as an artist early, during the first phase of his work. But he never felt the inner need to gain new impressions and inspirations by engaging with other cultural traditions and places. His fulfilled his ambitions and satisfied his need for emotionalism by only depicting seemingly random nature motifs. These were usually sweeping plains, the monotony of which was broken up by casually interspersed huts, sparse plantations, a wood, or a dirt track. Like the exponents of the Barbizon School, he painted groups of trees at the waterside and polder fields or he created visions within a wood. He was not interested in cityscapes or rural traditions. He brought the poor areas of Krakow to life with staffage.[11] His favourite accessories were geese and cows, but most frequently he chose a female figure which lent the compositions a warm, intimate character. The artist never tried to capture fleeting, barely perceptible changes in his landscapes dictated by the time of day, the play of the clouds or the terrain profiles; instead, what he captured on canvas were things that he considered permanent and enduring. All the components of his pictures were shown in scattered light. A low horizon and a high, cloudy sky form the space in which the person is no more than a barely perceptible speck and a somewhat insignificant part of the world.

Kochanowski’s palette was sparingly reduced to earthy tones and neutral shades. Only seldom can a smudge of red, white or blue be found between the green, the brown and the grey. Even when the artist uses a light green in his cheerful vernal landscapes, he does not allow them to be lit by full sunlight and he does not dramatise them with shadow contrasts. Kochanowski avoided portraying extreme conditions of nature. His pictures do not show sundrenched meadows, or a wood slumbering under a blanket of snow or a sky coloured the deep red of dusk. However, some of his works do have a formal component which lend them a certain disquiet. This relates to the way in which the colour is applied, which is done in short, strong strokes running in several directions, and in the restless, expressive lines of the trunks and branches of trees and of the clouds. Occasionally, the painting surface seems to vibrate slightly or to tremble somewhat in the wind, a trait which makes the artist resemble Camil Corot, who, however, was a lot more subtle and idealised reality more.

Stanisław Przybyszewski[12], who was impressed by Kochanowski’s paintings, wrote about him saying that he was a “great poet of the true soul of Polish landscape”.[13] These lofty words accurately describe the meaning of Roman Kochanowski’s painting, a man who knew like few others how to capture the essence and the mood of a landscape. His work is correctly identified with the landscape body of work that brought him fame and recognition. At the same time, it should be remembered that his legacy also includes many portraits and a few still lifes, including pictures of flowers.

Another of the artist’s passions was photography, an art form which was extremely popular with many artists at the end of the 19th century. Many even gave up the brush in favour of the camera. But almost everybody made use of the possibilities that photography offered them for their creative work. Roman Kochanowski exploited both advantages of the medium – as a form of artistic expression, where he particularly appreciated the design options. In his collections, which are housed in the Suwałki District Museum (Muzeum Okręgowe w Suwałkach), there are a number of photographs showing artistic qualities. The artist captured trees, cliffs and landscape formations on the plate. He was particularly interested in that fragment which represented the uniqueness, when seen close up, of that which otherwise seemed usual and familiar. With that in mind, he also experimented with mirrored copies by developing the same pictures in sepia and black and white.

Despite all this, however, Kochanowski remained a painter.

He used photography as a support function. He photographed his picture models, collected photos of human characters and traditional costumes from professional photographic studios and had his own imaginary museum in which he collated dozens of reproductions of contemporary Munich paintings, including paintings of Polish provenance.[14] However, the majority of his photographic estate is made up of landscape photographs. That which was at the centre of his painting also dominated his photography. He labelled hundreds of cardboard boxes with cryptic figures that only he could decipher. Amongst these landscape photos are some extremely interesting pictures depicting the reality of Galician villages and fairs as well as some of the region’s inhabitants, who stare into the camera with curiosity but also with fear. The number of photographs reflects Kochanowski’s passion for this medium.[15] The artist’s records include notes about how he and his fiancée developed pictures, went on trips to the countryside and talked about the purchase of a camera.

Another important part of Kochanowski’s artistic work was in the creation of objects, including coloured ceramic vases, screens and fans. He also worked with the Kraków magazine “Świat” on the graphic design of the magazine by designing cover pages and creating illustrations. Calendars were a form of publications close to his heart as well. Also amongst the drawings and sketches are some drafts, each with 12 drawings assigned to the months of the year. The artist also liked to create elegant fans embellished with miniature fans, a very popular accessory at the time.[16]

These artistic activities allowed Kochanowski to improve his finances since he was selling fewer landscapes as time went by and his works were being seen at exhibitions much less frequently. Over time, the artist was forgotten, partly because the National Socialists imposed a painting ban on him. Since he was no longer allowed to paint or exhibit, until the end of his life he drew landscapes which usually depicted a group of trees, a dirt track and the contour of a stooped peasant woman.

The last years of his life were hard for the artist: he was widowed and was not allowed to sell or show his pictures in public for the reasons already mentioned. Yet, he still did not decide to return to his homeland. He died in Bavaria and thus became the last “Münchener” from Poland.

Eliza Ptaszyńska, August 2020