Peenemünde: Poles and Hitler’s secret weapon – the V2 rocket

Mediathek Sorted

Peenemünde und die Polen - Hörspiel von "COSMO Radio po polsku" auf Deutsch

September 1992. Germany is preparing to celebrate the second anniversary of reunification on 3 October. At the same time, in the small village of Peenemünde on Usedom in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, with a population of less than 300, preparations are also underway for the 50th anniversary of the successful start of the V2 rocket (the “V” stands for “Vergeltungswaffe”, or “retaliation weapon”) on 3 October 1942. The German Aerospace Industries Association (Bundesverband der Deutschen Luft- und Raumfahrtindustrie) planned to celebrate this day as the birth of space flight. However, the association failed to mention the original military purpose of the rockets, which were built during the Second World War in the research centre on Usedom, as well as the many thousands of people in London, Antwerp and elsewhere who were killed or injured by aerial bombardments.

The planned events in Peenemünde caused an international outcry, and the celebrations were called off – although only at the last minute. This led to a debate, which ran for several years, about the role of science in the service of a totalitarian state. The Army Research Centre (Heeresversuchsanstalt) on Usedom, which at that time was one of the largest rocket construction sites in the world, is a good example of such a relationship.

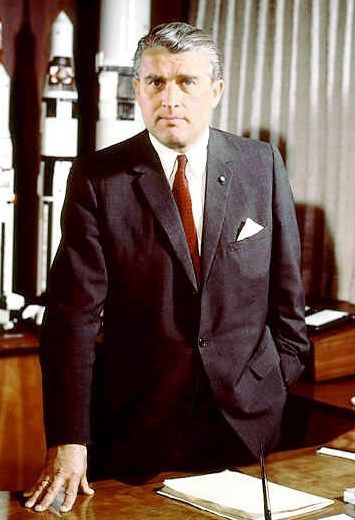

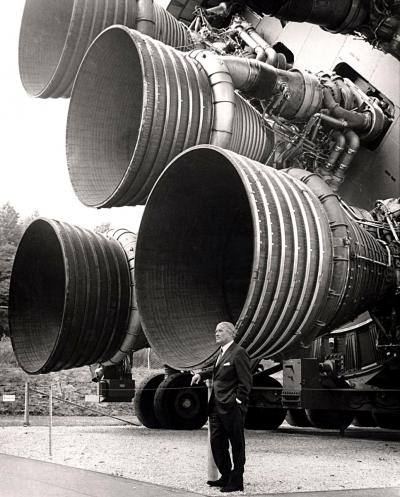

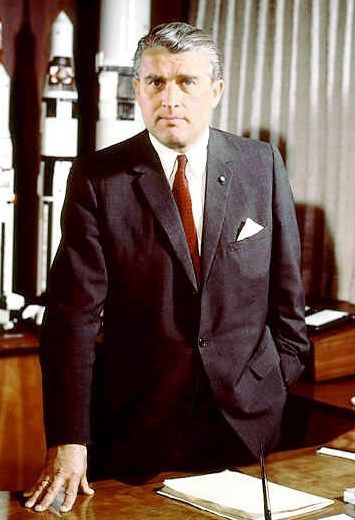

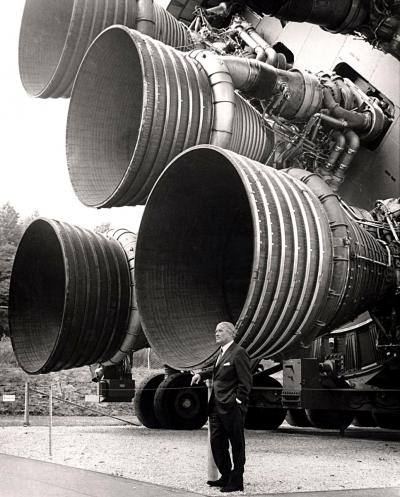

The first tests in which liquid rocket fuel was used were already conducted at the beginning of the 1930s in the Kummersdorf research facility, about 60 kilometres to the south of Berlin. However, the proximity to the large city made it impossible to expand the test site. The Third Reich had in the meantime set itself the goal of owning a completely unstoppable weapon. It was decided that the research centre should move to Peenemünde, a small fishing village on the northernmost point of the Baltic Sea island of Usedom. The site for the investment was selected personally by Wernher von Braun, a brilliant scientist and one of the main designers of the V2 rocket, who dedicated his work entirely to Hitler’s regime. The strategic location of Peenemünde appeared ideal as a military testing ground. The strip of coast on which the village lay made it possible to follow the flight path of the rockets for up to 300 kilometres. The village was moved to another location, and in 1936 was replaced by a military testing facility, with a base and an airfield for use by the German Air Force (Luftwaffe).

During the first few years of the facility’s existence, the scientists, engineers, and military experts were provided with essentially unlimited funds. The idea of creating a miracle weapon overshadowed everything else. When the Second World War broke out, work on developing the rockets intensified. An increasing problem, however, was that there were not enough people to work on the site. The only option was to bring in labour from other countries, even though the project had been classified as “top secret”. The first forced labourers arrived in Peenemünde and were later joined by prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners, among them internees from the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Their number increased from one month to the next. Most of them were Poles and Russians, although they also included French, British, Czech, and Dutch citizens. According to estimates, between 10,000 and 12,000 forced labourers were employed in Peenemünde in total.[1]

According to the National Socialist racial doctrine, the workers from Eastern Europe were classified as “subhumans” (“Untermenschen”). They were threatened with punishment, even death, if they made contact with the German population. They were treated far worse than the British and French, were given far smaller food rations, and were quartered in much more basic barracks. Leon Dropek, who arrived in Peenemünde in the summer of 1940 together with around 400 other Poles, described the conditions there as follows: “We were told that we had arrived here voluntarily, in order to work for the welfare and support of the Third Reich. The Poles from Łódź who passed us by gave us no reason to feel optimistic. They were dressed in poor clothing, were emaciated and despondent”.[2]

At first, Dropek was quartered with other labourers in the Peenemünde camp for German workers. “The barracks were arranged in a U shape, were painted white and looked quite ornamental with their red window frames. There were eight beds to a room, there was a shower, a bathroom, mattresses, and heating. The bedclothes could be changed every day. This idyll lasted for six weeks before we were moved to the camp where the Poles lived. Here, 14 men were housed in one room, there were three-tier bunk beds, old mattresses, old, dirty and ragged blankets, no pillows and no water; instead, there was a coal-fired stove. Due to the unhygienic conditions, our bodies were bitten bloody by lice, fleas and bedbugs. Every so often, the rooms were disinfected using agents that were so strong that they made knives, forks, and razors for shaving rust. After disinfection, the barracks were closed for 24 hours. They weren’t bothered where we slept. All they cared about was that we showed up for work the next day. Another night, we were almost poisoned by the disinfectant; we felt dizzy and spat blood. A week later, the bedbugs were back”.[3]

The research facility at Peenemünde was of extreme strategic importance. After Berlin and Hamburg, it was only the third place to be assigned its own electric S-Bahn (overground train) line. On 15 April 1943, 106 km of railway track were put into operation. There were two railway lines with twelve stops. The trains brought the workers to Peenemünde from the surrounding area every day between 5am and 11pm. The regulations governing transportation were also discriminatory towards Polish forced labourers. They were only permitted to use the last carriage. The directorate of the German Reich Railways (Deutsche Reichsbahn) even issued its own “Guideline for the transportation of prisoners of war and Poles”, which included a reminder, among other things, that Poles should wear a lilac “P” that was to be sewn in a clearly visible place on their clothing. Poles were also only allowed to use the railway on receipt of written permission by the local police, while workers from other countries, such as Belgians, French and Italians, were treated on equal terms with German passengers in the S-Bahn.

The vigorous effort put into planning the research centre meant that the labourers were forced to work on a number of different tasks. From 1936 onwards, a power station, an air separation unit, an airfield for use by the Luftwaffe with the full infrastructure, two ports, several launching pads for rocket tests, testing stands, accommodation complexes for scientists and civilian employees, and multiple forced labour camps were all built on Usedom in the space of just a few years. In Karlshagen, a village 7km away from Peenemünde, there were two concentration camps which were used as a satellite of the Ravensbrück men’s concentration camp.

The forced labourers were continuously monitored while they worked. There was a constant fear of being punished, even for the slightest misstep. Even so, occasionally Polish workers made attempts to delay the construction. Some of the Polish and Dutch workers also formed a resistance group, which convened with Dr Carl Lampert, a Catholic priest from Austria, and Johannes ter Morsche, a Dutch communist who lived in nearby Zinnowitz with his German wife. Both men passed on information to the workers about current developments on the front, which they received by listening to forbidden radio stations. However, the group was denounced. In October 1943, its members were accused of high treason and many of them were sentenced to death.[4]

The activities of the centre in Peenemünde were kept top secret. The island was surrounded by multiple barriers to prevent people from coming and going, and it wasn’t easy to get information out. However, it wasn’t possible to keep the secret for long. Even as early as 19 September 1939, an anonymous dispatcher offered to provide the British marine attaché in Oslo with valuable information about the Third Reich’s secret armament projects. In order to obtain the detailed information, the German-language news broadcast by the BBC was to be slightly altered on a specific date. After the agreed signal was transmitted, the attaché did indeed receive a detailed document, which has subsequently become known as the “Oslo Report”. It contained information about the construction of rockets and rocket facilities, radio systems and the distance measurements being conducted by the Germans. It was in this paper that Peenemünde was mentioned for the first time.

Despite the extensive information it contained, the British experts came to the conclusion that the report was a bluff by the Germans. They simply could not believe that one single person could have such a broad knowledge of secret weapons. Although reconnaissance planes were dispatched to Usedom, they were unable to detect the excellently camouflaged centre, particularly given the fact that the aerial photography technology at that time was still in its early stages. The British then shrugged the document off as a matter of no importance. The document remains the biggest conundrum in the history of the secret services. Despite an avid search for its author, he or she was never found.

In the years that followed, more information came into the hands of the British secret services about new weapons that were being tested by the Nazis. The secret service of the Armia Krajowa (AK), the Polish Home Army, whose agents investigated all rumours surrounding Hitler’s unique miracle weapon, played a particularly important role here. At the turn of the year 1942/43, the engineer Antoni Kocjan, head of the air reconnaissance service of the AK, received some information from a Pole who had been transported to Königsberg as a forced labourer, where there was a training centre for operating teams for the rocket launching pads. This informant spoke of German experiments with new weapons on an island near Stettin (Szczecin). He thought that this weapon was intended to destroy London. The report on Peenemünde was immediately passed on to the British, who again sent a reconnaissance plane to Usedom. This time, the information about the secret research centre was confirmed. Important details were also provided by the engineer Jan Szreder, codename “Furman”, who was sent to Usedom by the AK secret service in 1943 as a voluntary worker. Through the German employment bureau, he took on a job as a driver in Swinemünde, where he delivered food to the military centre. With its numerous control posts and barriers, Peenemünde remained closed to civilians. However, “Furman” was able to find out quite a lot about the existence of the concentration and prisoner camps, as well as the camp for forced labourers, where thousands of foreigners were living. He also listened in on a conversation among the Germans, in which there was talk of “air torpedoes” that were similar to small aircraft and which were launched from special launching pads.[5]

This information was confirmed by Augustin Träger (codename: “Tragarz”), who also added further details. Träger was an Austrian who after the outbreak of the Second World War became a German citizen. He lived in Bromberg (Bydgoszcz) and was cooperating with the Polish resistance. By sheer coincidence, Träger’s son Roman was called up to join the Wehrmacht, and was stationed on Usedom near the test facility. His father persuaded him to pass on information about Peenemünde to the Poles. He agreed, and became an AK agent, codename “T2-As”.

Roman Träger’s reports reached London via the AK air reconnaissance service, where on 29 June 1943, after long discussions at a meeting of the Cabinet Defence Committee, the decision was made to bomb the centre on Usedom. The plan was to dispatch Royal Air Force planes just six weeks later. In the interim, the air attack was planned down to the tiniest detail. After the end of the war, Sir Arthur Harris, Marshal of the Royal Air Force, said that “No air attack was prepared so precisely and so conscientiously”.[6] The British decided to distract the Germans by first bombing Berlin prior to attacking Peenemünde. Instead of taking the direct route, the RAF planes flew along the Baltic coast above Peenemünde before turning towards Berlin.

The actual attack on the Peenemünde rocket facility took place during the night of 18 August 1943. In one of the largest air raids of the Second World War, a huge fleet of nearly 600 four-engined bombers dropped a total of 1,937 tonnes of bombs onto the research centre and the surrounding area.[7] In his book, “Akcja V-1, V-2”, Michał Wojewódzki quotes from the reports of the Poles who were on the island during the attack. Henryk Skoczylas, who was working for a German farmer in Bannemin near Zinnowitz, described that night as follows: “Truly, it is almost impossible to describe what happened in Peenemünde and on the western part of the island. It was a night of horror. It seemed as though waves were rolling in the ground under our feet, and as though the island would burst and sink into the sea at any moment. (...) Above Peenemünde, where you would otherwise see strange German small aircraft being shot into the sky, all hell broke loose!”.[8]

The damage caused to the centre in Peenemünde was enormous. Of the 80 buildings there, 50 were completely destroyed. The buildings where the scientists lived suffered the most damage. Nevertheless, two large production halls survived almost unscathed. Due to an error of the pilots, which occurred due to the poor visibility, bombs also fell onto the barracks of the forced labour camp in nearby Trassenheide. During the air raid, 735 people in total were killed, of whom 178 were members of the German staff. The victims also included a close colleague of Wernher von Braun: Dr. Walter Thiel. Most of those killed were prisoners and forced labourers, particularly Poles and Russians. However, the British also suffered heavy losses, with 42 planes shot down by the German air defence.

After the air raid on Peenemünde, the start of mass production of Hitler’s “miracle weapon” and its use had to be put back by several months. The rocket tests were put on hold until October 1943. The production of the rockets was relocated to an underground factory owned by the Mittelwerk company near Nordhausen in the Harz mountains. For testing purposes, a V2 launching pad was built on the site of the Heidelager SS troop training area in the village of Blizna, about 50 km to the east of Rzeszów. This meant that they were out of range of the British and US bombers.

The construction project in Blizna very quickly attracted the interest of the Polish AK agents. Initially, the Poles weren’t entirely sure what the Nazis were up to. The AK spies observed an increased level of activity among the soldiers. They also noticed new, additional security measures all around the troop training site. Within a short space of time, an increasing number of SS men were entering the area, and the site was surrounded by anti-aircraft guns. The agents also witnessed other strange developments. In the village, which had already been evacuated and burned to the ground, the forced labourers were given the task of building plywood models of houses, barns, and sheds. Dogs made of plaster were placed in front of the buildings, and dolls made to look like real villagers were also sighted. From afar, therefore, particularly from the air, the village looked as though it were inhabited. The aim was to prevent an attack from the air on the troop training ground close by. At the end of November 1943, the rocket tests were resumed, this time near Blizna.

It became very difficult for the AK agents to do their work. However, the officials working for the forestry office in Wola Osiecka proved extremely helpful when it came to obtaining information, as well as parts of destroyed rockets. As the Germans informed the Poles in specially produced handbills, taking possession of rocket parts was a crime punishable by death. All information that was gathered was immediately passed on to the AK leadership. The rocket parts went to Polish scientists, who secretly examined them.[9] Their findings were then forwarded to London.

It soon became cleare that the Poles had not succeeded in procuring enough parts to fully reconstruct the rocket. Meanwhile, the British, who were increasingly fearful of air attacks on their cities using the new Nazi weapons, were paying close attention to the machinations of the Germans. They issued an urgent request to the AK leadership to deliver a detailed technical description and a list of the individual rocket parts as quickly as possible.

Under pressure, the supreme commander of the AK, General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, agreed to procure a rocket by force while it was being transported by train. A stretch of forest between Tarnów and Brzesk was chosen as the site of the attack. The soldiers of the AK were to take out the crew of the German train and unload the rocket onto a special vehicle using a crane. The plan had already been thought through down to the tiniest detail when in May 1944 a message was received that caused the attack to be called off. In the village of Sarnaki on the Bug river, in the direction of which the rockets were fired in Blizna, an unexploded V2 rocket had been found.

In his diaries, Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, remembered the event as follows: “The rockets fell many miles apart from each other. Each time, the German patrol troops would run to the site of the explosion and gather up the parts. One day, however, a rocket fell onto the banks of the Bug without exploding. The Poles reached the place of impact first, rolled it into the river, waited until the Germans had abandoned their search, later hauled it out and under cover of darkness, dismantled it”.[10] According to various reports, the rocket was retrieved from the river using teams of horses or tractors. The dismantled rocket parts were hidden in secret crates in three lorries that were used to transport potatoes. In this way, it was possible smuggle the parts to Warsaw, where the decision was soon taken to pass them on to the British.

The plan was then for a British plane to fly the rocket parts out of Poland as part of the “Most III” (“Bridge III”) operation. It was considered to be extremely difficult to land a plane in the occupied territories and to prepare it for the return flight. The most important parts of the missile were hidden in oxygen bottles, the bases of which were removed and then re-welded back on. They were then brought from Warsaw to a site close to Tarnów. Despite repeated routine checks, the Nazis failed to find the hidden cargo.[11]

A provisional landing site was created to the north-west of Tarnów, in the “Łąki Przybysławskie” (“Przybysław Meadows”). It was secured by more than 200 people, AK troops and the inhabitants of the surrounding villages. Due to heavy rainfall and the anticipated problems with landing on the unsurfaced ground, the take-off of the British plane was delayed. Finally, during the night of 25–26 July 1944, Operation “Most III” was given the go-ahead. The two-engine plane “Dakota” took off from the base at Brindisi in Italy. Those on board included envoys from the Polish government in exile, who were to be flown in to Poland. Five people were due to board the plane for the return flight, including Captain Jerzy Chmielewski (codename: “Rafał”), a secret service officer of the AK who was responsible for transporting the precious cargo.

The operation had to be carried out with extreme care, since German troops were stationed close to the landing site. At first, all went according to plan. After landing, the plane was loaded in just 15 minutes. The problems started when the plane attempted to take off. The pilot tried to lift off three times in a row; however, each time, the chassis became mired in the soft earth. A decision was made that the crew and passengers should disembark and that the plane should be incinerated. However, some of the AK members decided instead to free up the chassis by pushing wood logs from the surrounding forest in front of the wheels. Finally, the engines started to rev up and the plane took off. The entire operation was originally due to last just 10 to 15 minutes. However, it took over an hour before the “Dakota” was able to leave the landing site.[12]

Despite all these efforts, the Nazis did ultimately succeed in using the V2 rockets during the course of the war, albeit to a far lesser degree than originally planned. The air raids on London, Paris, Maastricht, Antwerp, and elsewhere led to the deaths of about 8,000 people. Even so, the bombing of the research centre in Peenemünde and the information about the missile obtained through the AK’s spying operation delayed the start of mass production and may have influenced the course of history. The hastily produced rockets often failed to ignite, or did not reach their target. The Nazis’ hopes for a “miracle weapon” were not fulfilled.

The part played by the Poles in discovering the V2 programme was not honoured internationally. After the war ended, the British took much of the credit for obtaining the information, while for a long time, Wernher von Braun, the “father of space flight” was celebrated in Germany as a cult figure. The scientist who dedicated his work to National Socialism was never brought to justice for his part in creating this lethal weapon. After Germany capitulated, he handed himself over to the Americans and emigrated to the US, where in 1958, he became the Director of the NASA Space and Rocket Center in Alabama. There, he developed the “Saturn V” rocket, which was used to take Neil Armstrong to the moon in 1969. Partly as a result of his collaboration with Walt Disney on a series of films about the conquering of space, Wernher von Braun became a popular figure for millions of Americans.

However, the Poles who were involved in unlocking the secret of the missile suffered a very different fate. After an unexplained attempt on his life, Jerzy Chmielewski, the secret service officer who brought parts of the unexploded rocket to London, emigrated to Brazil and never returned to Poland. Antoni Kocjan, the head of the AK air reconnaissance, was arrested by the Gestapo for making grenades, and was executed in August 1944 in the Pawiak prison in Warsaw.

Monika Stefanek, February 2018

The Historical Technical Museum in Peenemünde documents the history of the construction of the V2 rockets.

Museum address: Im Kraftwerk, 17449 Peenemünde

Website (also available in Polish): https://museum-peenemuende.de/?lang=en

Film:

The spy film “Die gefrorenen Blitze” (“Frozen Flashes”) directed by János Veiczi, is based on the quest to unlock the secret of the V2 rockets. The film includes archive footage from the Second World War. Cast: Leon Niemczyk, Alfred Müller, Emil Karewicz, Dietrich Körner, Renate Blume and Ewa Wiśniewska. Production: DEFA film studios, 1967.

Film trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dKqqOAlnEjg