Monika Czosnowska

Mediathek Sorted

Monika Czosnowska – Portraits or GeneraI Images of Humanity

In an essay on the “Aesthetics of Photography” published in the periodical Kunstforum international in 2008 Paolo Bianchi wrote “The overpowering flood of images from the age of information drowns the a person's perceptive capacities to such an extent that the imagination is unable to find any place to rest in peace”.[1] If we wished to describe the same situation today, nine years later, there are no more superlatives available. Indeed there seems to be no more room for artistic portraits of people between the images of politicians and VIPs from all over the world that are transported into our familiar homes every day, and the approximately 1,000,000 selfies that are taken every day all over the world with digital cameras, smartphones and tablets. Almost everyone has at some time posted a self-portrait as a “profile picture” on Facebook and Twitter, whereby it seems to be a given fact that the origin, social status and personality of the individual are disassociated. In addition, theoretically speaking, today every country on earth has access to the total physiognomy of its citizens thanks to the photos in identity cards and passports.

Furthermore, there is no clear distinction between artistic and amateur photography in the area of portraits and images of people. This applies equally to photos of VIPs and models and to photo-reportage and picture journalism, all of which also claim to be art. Soon after the invention of photography portraits became one of the most important themes of the new medium, initially in the form of a daguerreotype and from 1860 onwards in the design of visiting cards. The photograph replaced hand-painted and hand-drawn portraits and made unique images available even to people of little income.

Artists reacted to the new flood of photographic portraits by inventing documentary photography. Starting at the end of the nineteenth century the famous photographer, August Sander (1876-1964) took hundreds of photos of individuals, families and groups, not on special commission but in order to document typical representatives of professions and social classes. In doing so he produced an “outline of the social orders currently existing in Germany”.[2] At the end of the “golden” and “wild” 1920s, when Sander's photographs began to appear in print, the portraits taken by Edward Steichen (1879-1973), of film stars VIPs and fashion models enjoyed an initial boom in popular magazines like Vogue. Others like the Polish/Jewish photographer, Helmar Lerski (1871-1956) took pictures of athletes, workers, nudists and “everyday heads”, partly out of research interest, partly to affirm particular ideologies, or out of interest in developing the medium of photography. During the Third Reich, Erna Lendvai-Dircksen (1883-1962), published volumes of photography with titles like “Das deutsche Volksgesicht” containing allegedly racial and typological characteristics of many different “tribes”, which were then exploited by the Nazis.[3]

After the war, photo journalists like Will McBride (1931-2015) and René Burri (1933-2014) in his photo essay “The Germans”, documented the lifestyle of the generations in the years of “reconstruction”, and the newly arising youth culture. From the 1960s to the 1980s photographers like Diane Arbus (1923-71), Larry Clark (*1943) and Nan Goldin (*1953) portrayed people in their social surroundings and on the edge of society. In the Street Photography pictures by Garry Winogrand (1928-1984) and Beat Streuli (*1957) the street was turned into a stage. Thomas Ruff (*1958) threw a spotlight onto “soulscapes” with his monumental, highly detailed portraits in passport photo style. Since the start of the new millennium Lukas Einsele (*1963) has been dedicating himself to “catastrophe journalism” with portraits of landmine victims in all four corners of the world, in which he is trying to restore self-confidence and optimism to his subjects.

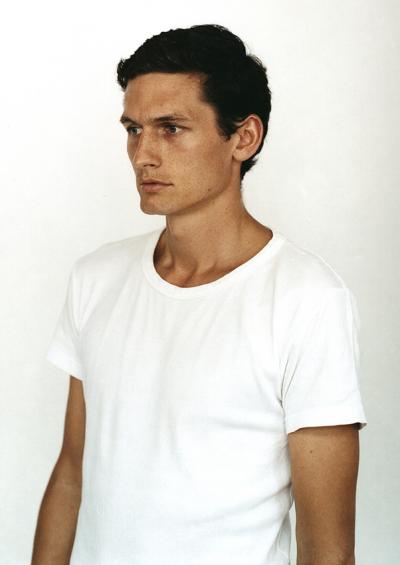

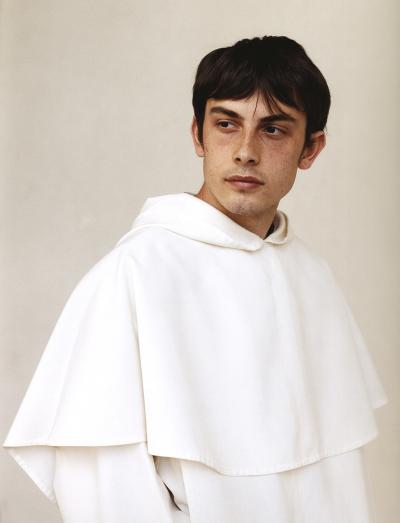

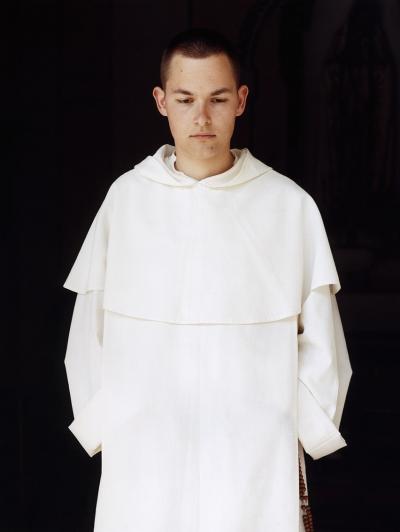

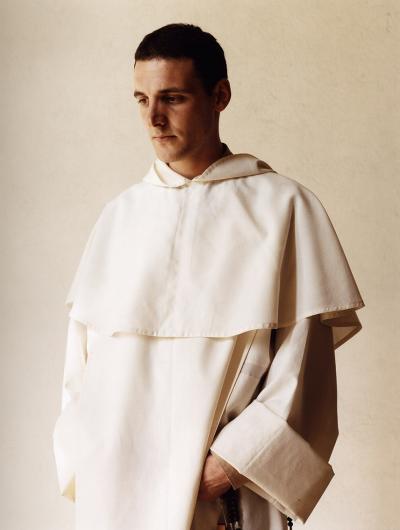

Over against the sheer inexhaustible variety of historical and contemporary categories in portrait photography, Monika Czosnowska has been developing a unique language of images since the start of the new millennium. She was born in Szczecin in 1977, came to Germany as a child and went to school in Braunschweig. In 1997 she began a course of study in graphic design and photography at the Folkwang University of the Arts in Essen. After basic studies in painting, graphics and drawing she decided to specialise in artistic photography. She studied under Bernhard Prinz, a professor for artistic photography, and Herta Wolf, a professor for the history and theory of photography. In the year 2000 she lived for a few months in Kraków and was inscribed as a guest student in the department of art history at the Jagiellonen University. Here she made an intensive study of portrait painting in previous centuries. In 2002 she was awarded an Erasmus grant to study at the College of Design in Zurich. In 2004 she completed her diploma studies in Essen with a series of photographs entitled “Novices” (Ills. 9-17), taken in Polish monasteries. In the same year this series made her one of the 10 prizewinners in a new competition for university students entitled gute aussichten – junge deutsche fotografie[4]: the jury consisted of the founder, Josefine Raab, the internationally famous photographer Andreas Gursky, and Mario Lombardo, the art director of the music and pop culture magazine, Spex. Since then Czosnowska has been regularly exhibited in the annual worldwide exhibitions presented by this promotional project for young talent. The most recent exhibition, held in the Museo de la Cancilleria in Mexico City from April to June 2017, was entitled gute aussichten deluxe – junge deutsche Fotografie nach der Düsseldorfer Schule. The exhibition will also be shown in the Haus der Photographie in the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg from January to May 2018. During her studies Czosnowska lived in Cologne: she is married to the actor, Jens Münchow, has two children and now lives in Berlin.

Her photos of children, young people and young adults, taken as bust, half length or three-quarter length formats, and showing them sitting or standing before a neutral background, seem to have been influenced by portrait paintings in previous centuries, a factor which has been pointed out on several occasions.[5] The clearest example is surely her portrait of “Larissa” (Title photo, Ill. 9) from the series of “Novices” taken in 2004: the seated pose, and the clothes, the direction in which she is looking and even some parts of her physiognomy like the nose and mouth seem to have been inspired by the famous picture by Jan Vermeer (1632-1675), entitled “Girl with a Pearl Earring” (ca. 1665, Mauritshuis, The Hague). This is partly accidental, because the habit worn by the novice in the photograph in a Polish monastery – and of course her appearance – are authentic. In an interview Czosnowska explained that she had not staged her photograph consciously: “From the very start I never intended to photograph Larissa in the pose of the “Girl with a Pearl Earring”. But Jan Vermeer is one of my favourite painters and I think that the novice's bonnet may have provided me with some inspiration for the photo. It may also be the fact that I then [later] selected the photograph on the grounds of the composition”.[6]

There are no further congruences in her photographic portraits to any of the other thirty-seven known paintings by Vermeer, but there are similarities to other early paintings. The startling hairstyle, the position of the head and the hands in the broad sleeves in the photograph entitled “Monika” (Ill. 1) – the earliest portrait taken in 2001 from Czosnowska's series of individuals – resembles the painting “The Woman’s Window (La Donna della Finestra)” (1879, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA) made by the British symbolist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). “Clara” (2007. Ill. 8) seems to have been modelled on this picture with the difference that the photograph shows her with a twig of ivy, whereas Rossetti has arranged peonies on both sides of his subject. Paintings by another symbolist, John Everett Millais (1829-1896), like the “Bridesmaid” (1851, Fitzwilliam-Museum, Cambridge) and “The Martyr of the Solway” (1871, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) might also have come into question as models. Millais' “Sweetest eyes that were ever seen” (1881, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh) is somewhat similar to Czosnowska's “Lea” (Ill. 45) in her series of “Elites” taken in 2017: in particular the direction of the gaze, her hair, her posture and the way she holds her arm.

Here it should be mentioned that in the symbolist pictures, a large amount of features attributed to the subjects were not only deliberately symbolic but were also placed against rich backgrounds, whereas Czosnowska's subjects have no symbolic function, are dressed in very simple clothing, mostly without jewellery, and are placed against a neutral background. Anyone who searches long enough is bound to find further models from other epochs of portrait painting. But this cannot be what the photographs are all about. For Czosnowska has herself stated that when she composes her photographs she never has any specific paintings in mind. That said, she has admitted that as a rule her use of a semi-profile, a bent head and a shoulder posture correspond to serene classical poses.[7] Since the Renaissance the semi-profile has been the most common form used in portraits, whereby both the head and body were pointing in the same direction at the time. Examples that come to mind here are paintings by Hans Holbein (1497/98-1543) and Lucas Cranach (1515-1586). Only during the baroque era was the body placed in a different direction to the head and here the gaze of the subject was mostly directed beyond the viewer. This is the case with Vermeer and also with Czosnowska. Even Rembrandt's youthful “Self Portrait with Gorget” (ca. 1629, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg) would be a perfect example. His complete pose is reproduced once more in the photographic portraits of “Jan” (Ill. 22) from the 2008 series of “Pupils” (Ill. 18-27), and of “August” (Ill. 18) even in the shape of the nose, the eyebrows and a hint of the forelock.

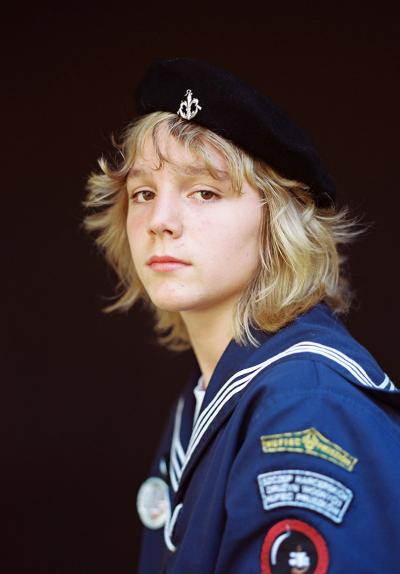

Czosnowska selects her subjects from closed social networks like school classes, boy choirs, Boy Scouts and Girl Guides and monastery communities, as a rule in Poland. The new series “Elites” (Ill. 40-47) was made at a sport grammar school in Berlin. However she also finds individual models (Ill. 1-8) on the street: “I keep my eyes open all the time, scan faces, and am permanently looking for the right physiognomy, the right expression that fits my pictures exactly. When the spark lights up, when I see the right missing face, then everything comes together before my inner eye to become the later picture.”[8] She not only finds faces that she recognises from her early childhood in Poland. In Germany too she maintains she is continually fascinated by Slavic-looking features. These physiognomies remind her of her roots, she says: they link her with inner human values like virginity, innocence and purity. We might also add that her images express blamelessness and integrity, indeed inner beauty.

In order to achieve this effect and to push the personality of her subjects into the background, she selects her models from groups with the same sort of clothing like school uniforms, surplices (Ill. 18-27), monastery habits, scout and guide uniforms (Ill. 28-39), and sporting gear. She dresses persons she finds on the street in clothes taken from her wardrobe at home; these are preferably somewhat out of date, and in the case of an emergency she uses a neutral shirt or blouse. As in older portrait paintings her models not only gaze beyond the viewer, they are also restrained, uninvolved and introverted. Adults are able to turn their gaze inwards when they are considering something carefully or do not wish to intrude too much on the people they are talking to, but with children this is more difficult to do. Czosnowska solves this by asking her subjects to repeat a multiplication table to themselves in their heads. The introverted gaze plays a particular role in her series of “Novices”. It is given an additional concision by the occasionally audacious and occasionally humble bent of the heads as in “Adrian” (Ill. 11), “Agnes” (Ill. 15) and “Justus” (Ill. 16). In painting we can find this sort of look primarily in the faces of Saints, and in the late 19th century in popular chromolithographs that were used for pictures of saints and mural prints of family idylls particularly in Catholic regions.[9] It might also be the case that Czosnowska's childhood impressions derive from there.

She works with a Pentax medium format camera, analogue Kodak films and takes her photographs exclusively in daylight shining from the front, thereby lighting up the faces uniformly. She says that this makes her work softer, perhaps even more painterly. She prints her pictures herself in professional laboratories where she is able to have a direct influence on the quality of the colours and the contrast between light and dark, possibly all the way to “a touch of idealism”. Finally she changes the names of the people she portrays and gives them first names that “have nothing to do with fashion and which condense the photographs to a final valid image.” All the individual characteristics and phases of the design – the choice of models, their physiognomy, expression, poise and pose, the direction in which they look, their clothes, the lighting and finally her printing technique – contribute to the expression and effectiveness of every individual portrait. “I stage my photographic work in order to attain precisely the expression I am looking for.“[10]

Of course, this throws up the question as to whether her images are strictly speaking portraits, i.e. renderings of specific persons, or rather more generally valid images of the human condition. As art academics used to say, the conventional definition of a portrait or an image is “a picture of a person that reflects a certain personality”, (Percy Ernst Schramm). The decisive factor here is, according to the Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, “the presentation of a specific person, not the degree of similarity, that can only be attained at specific times and with limitations”.[11]

The various means used by Czosnowska are in no way a rejection of the portrait genre but from the point of view of the portrait artist, always of benefit to both sides, the subject and the photographer herself. Anyone who wishes to be portrayed – in painting this has been the case since the mid-fourteenth century – wanted to be presented in specific clothing, with a specific attitude and pose. In other words they wanted to be staged. Hence artists attempted to place their subjects “in the right light” and deliver attitudes and poses conforming to social norms, i.e. to come up with a skilfully perfect “portrait” (lat. protractum, drawn out, extended) or “counterfeit” (latin: contrafactum, imitated), as people said in the age of Dürer. When a portrait was made it was almost compulsory for this to be preceded by a commission from the subject him/herself, from a relative, or out of public interest. In the area of representative and clearly recognisable pictures, people could only be certain of being portrayed when they had attained a certain level of importance, as a result of their social status, their wealth, and public influence, or the fact that they were criminals or in the worst case, were seriously physically deformed.[12] Hence the names of the people portrayed were as a rule well known, unless their identities had been lost over the centuries.

VA good example here is the reformer,Martin Luther who became famous – in the eyes of some people, disreputable – when he nailed his 95 theses to the door of a church in Wittenberg in 1517, following which he was ordered to appear before the Reichstag in Augsburg and was forced to defend his theses in Leipzig in June 1519. There are around 500 known portraits of him, whereas there is not a single extant portrait of his predecessors, John Wyclif and Johannes Hus.[13] Even then people were very conscious of the psychological effect of images and placed great value on a corresponding design. Lucas Cranach, for example, made a copper engraving of Luther's bitter opponent, Cardinal Albrecht von Mainz, with an exhausted expression, hanging shoulders and a carelessly buttoned jacket, whereas he portrayed his adversary, Luther, with a sharp profile, alert face and a starched robe.[14] Some time later in 1521, woodcuts and engravings showed the reformer as a saint with a dove and a huge halo filling the picture – such portraits naturally came from the hand of artists like Baldung Grien and Hieronymus Hopfer, who admired Luther. He has also been etched into our memory today as “Junker Jörg” with a jutting chin, a heavily twisted beard, a haughty expression and a dashing robe: the portrait in wood was made in 1522 by Cranach for propaganda purposes for Luther's sovereign, Prince Friedrich the Wise of Saxony.[15]

Czosnowska in no way uses any of the known features for a portrait, like a private commission or public interest; she neither identifies a person by his/her real name, nor does she allow her subjects to have any say in their clothing or other recognisable features of their personality. For the viewer her pictures are not images of a “certain personality”, as defined by Schramm, but all of them show general human features. They are idealistic images of traditional values like “virginity, grace and purity”. “These values have been stamped in my character since my childhood”, says Czosnowska, “and I capture them in my pictures, although I think that they have gone a little out of fashion over the past few years.“[16] The subjects themselves, their relatives and friends are only given one copy of the portrait, most of which show their subjects in a fleeting stage of development. It might be the case that they do not even like their portraits because they do not look happy and are not wearing their favourite garb.

Even when Czosnowska's images have an uncertain status there are points of contact with painting. Since the Renaissance, artists have used real persons in crowd scenes and love scenes in order to present allegories and personifications. They did this by engaging and paying models or using previously drawn sketches on pieces of paper and notebooks as models for representative paintings. In the Dutch baroque age, when almost every citizen was able to afford paintings in order to satisfy their love of art and furnish their own apartments, genre presentations developed side-by-side with portraits. The latter were pictures of people, mostly women engaged in simple activities at home , at work on the land, or waiting for a ship. In his famous study on Dutch culture in the 17th century, Johan Huizinga wrote that: “All these insignificant figures appear to have been transported far from their usual surroundings into a sphere of clarity and harmony where words are no longer uttered and thoughts no longer exist. What they are doing is utterly mysterious like the things we believe we are seeing in a dream.“[17] Here Huizinga is referring to Vermeer – and we only have to think of “The Girl with a Pearl Earring” – where a portrait mediated by an everyday presentation and a particular genre, can be clearly condensed into an allegory of generally valid inner values.

Art historical interpretations always run into trouble when the names of the subjects have been lost or are not mentioned, and there are no indications of any identity like insignia, uniforms or unique facial features. The most famous example is Leonardo da Vinci's portrait of the “Mona Lisa” (“La Gioconda“, ca. 1503/06), where critics are still disputing whether we are being given an idealised image or the portrait of a real person. It is a similar problem with Vermeer's “Girl with a Pearl Earring”: here we do not know whether this is a character study of a paid model, the image of a particularly beautiful woman from the artist's neighbourhood, or a commissioned portrait. These unknown factors are precisely what inspired the author Tracy Chevalier to write a recent novel, and the film director, Peter Webber, to make his multi-award-winning cinema film.[18] The question of whether a work of art is a portrait or simply a human image is still disputed today with regard to a huge number of heads and busts made by the sculptor, Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919). Scholars are still tying to clear up which works are portraits and which are simply meant to express a specific, general image of humanity.[19]

Czosnowska's photos take up a position between the two. That said, the concept of a “portrait” has a general everyday validity for her, since she always allows the children, young people and young adults in her pictures to see them as reproductions of themselves. They might also have had no objection to their portraits being categorised by art scholars as a generally valid personification of humanity that has little or nothing to do with the time the photos were taken. The boundaries will be moved once more in the course of time. When they are old the persons in the portraits might even be pleased to possess an “authentic” portrait from their childhood. Decades later, when their real names and the circumstances behind the photo have been wiped from people's memories, viewers will be able to take up the discussion once more as to whether these are “portraits” or possible allegories of a long past human ideal.

Czosnowska's works claim a special position in contemporary photography. If we browse through the relevant literature,[20] we rarely come upon picture series of children and young people. Since the end of the 1980s a Dutch woman by the name of Rineke Dijkstra (*1959) has been looking for models with no artificial poses and possessing a natural aura. She found them in the form of children in bathing costumes on the beach and photographed them for a decade. The U.S. artist, Sally Mann (*1951) made a name for herself with pictures of children in idyllic staged dreamlike family settings. During the transition years between Socialism and capitalism the Russian/Ukrainian photographer, Sergey Bratkov (*1960), documented homeless young people engaged in petty crime alongside other people at the edge of society. In contemporary artistic photography it is almost impossible to find any images of people (over and above documentary images), like those taken by Czosnowska, which as she herself admits “have gone a little out of fashion”. Even when we seek advice on “beauty” in contemporary art,[21] we find many different categories, primarily on the absence of beauty and the resistance to what is deemed beautiful. Nonetheless there are scarcely any attempts like those made by Czosnowska, to stage inner beauty as the essential feature of humanity in general.

Axel Feuß. October 2017

Further reading:

Eleven. Monika Czosnowska, published by the Kunststiftung der ZF Friedrichshafen AG, Exhibition catalogue Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, 2008

Die beste aller Welten, published by Thomas Niemeyer, exhibition catalogue Städtische Galerie Nordhorn, 2014

The artist's homepage: www.monika-czosnowska.de containing lists of her solo and group exhibitions.