Monika Czosnowska

Mediathek Sorted

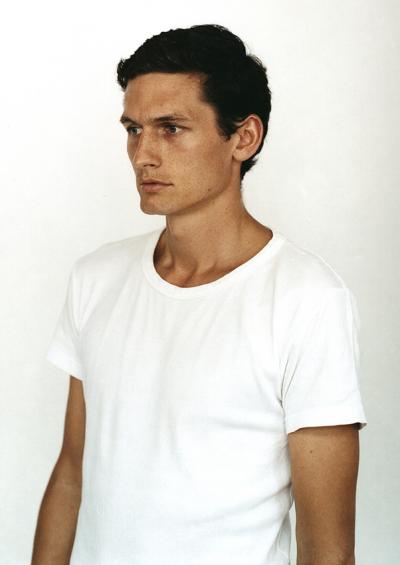

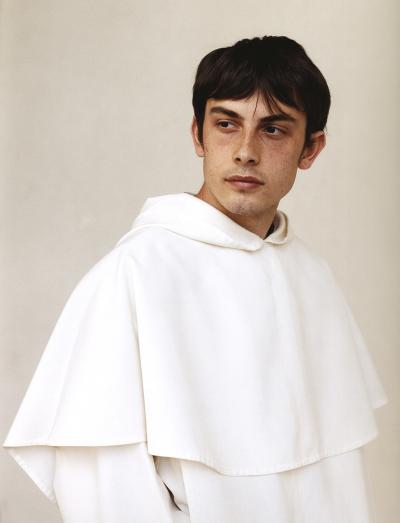

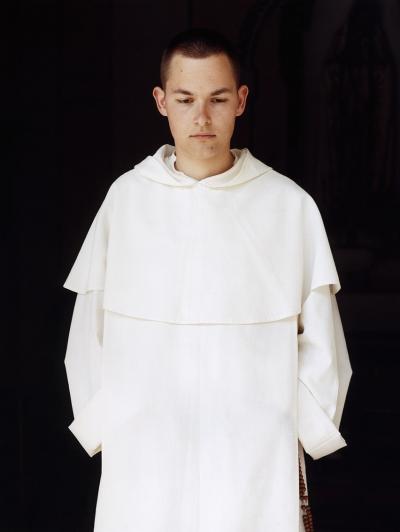

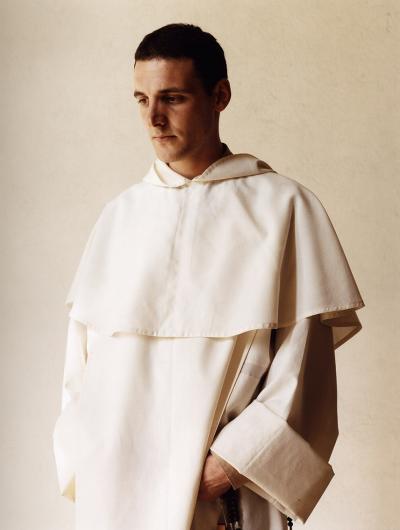

Czosnowska in no way uses any of the known features for a portrait, like a private commission or public interest; she neither identifies a person by his/her real name, nor does she allow her subjects to have any say in their clothing or other recognisable features of their personality. For the viewer her pictures are not images of a “certain personality”, as defined by Schramm, but all of them show general human features. They are idealistic images of traditional values like “virginity, grace and purity”. “These values have been stamped in my character since my childhood”, says Czosnowska, “and I capture them in my pictures, although I think that they have gone a little out of fashion over the past few years.“[16] The subjects themselves, their relatives and friends are only given one copy of the portrait, most of which show their subjects in a fleeting stage of development. It might be the case that they do not even like their portraits because they do not look happy and are not wearing their favourite garb.

Even when Czosnowska's images have an uncertain status there are points of contact with painting. Since the Renaissance, artists have used real persons in crowd scenes and love scenes in order to present allegories and personifications. They did this by engaging and paying models or using previously drawn sketches on pieces of paper and notebooks as models for representative paintings. In the Dutch baroque age, when almost every citizen was able to afford paintings in order to satisfy their love of art and furnish their own apartments, genre presentations developed side-by-side with portraits. The latter were pictures of people, mostly women engaged in simple activities at home , at work on the land, or waiting for a ship. In his famous study on Dutch culture in the 17th century, Johan Huizinga wrote that: “All these insignificant figures appear to have been transported far from their usual surroundings into a sphere of clarity and harmony where words are no longer uttered and thoughts no longer exist. What they are doing is utterly mysterious like the things we believe we are seeing in a dream.“[17] Here Huizinga is referring to Vermeer – and we only have to think of “The Girl with a Pearl Earring” – where a portrait mediated by an everyday presentation and a particular genre, can be clearly condensed into an allegory of generally valid inner values.