Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski

Mediathek Sorted

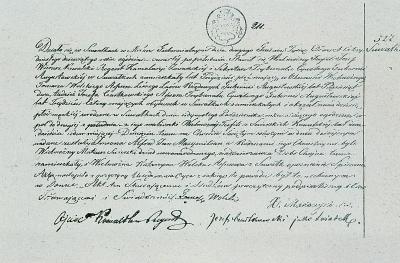

Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski was born in Suwałki on 11th October 1849 (Ill. 2). Many years previously his father had moved there in order to work as a lawyer. The small rural town, whose population only numbered a few thousand, lay between lakes and forests. Its inhabitants were generally poor and belonged to a number of different groups. Other than Poles and Jews, the majority of people living here were Russian, since this part of Poland was under Russian domination at the time.[1] Military barracks were built on all four traffic arteries in the town. The cultural and artistic life of the town could be described as meagre. There had been no previous artists in the Wierusz-Kowalski family, whose roots date back to the 13th century. The talents and sensitivities of the future painter developed in these surroundings. There are no further documentary records of his childhood years apart from his baptismal certificate (Ill. 3).[2]

In 1865 the Wierusz-Kowalski family moved to Kalisz in the middle of the country. The Talmud, one of the oldest in Poland, offered more culture, and more heavily developed educational system and better job possibilities.[3] There Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski attended a grammar school that enjoyed a good reputation: one of the teachers of drawing and calligraphy was a trained and talented – if only provincial – painter by the name of Stanisław Barcikowski.[4] We cannot rule out the fact that he recognised his pupil’s talents, for he then left Kalisz (Ill. 4) in 1868 to move to Warsaw. Here he attended the drawing class, the sole institution for artistically talented youths.[5] During this time he also visited the private workshop of the highly talented painter and excellent pedagogue, Wojciech Gerson, who was the teacher of many artists.[6] He taught his students the techniques of painting from the very start: they were schooled in observing nature, which should be regarded as the great master, and in doing so they learnt many things about the history of art. Despite everything, visiting the drawing class was not particularly important in Wierusz-Kowalski’s apprenticeship, even when moderately talented artists like Rafał Hadziewicz and Aleksander Kamiński were active here.

The next step in the training of the future painter led him to the Art Academy in Dresden. This was an unexpected choice because the Dresden School was anything but popular. The courses left a lot to be desired. On top of that Polish family names hardly appeared at all amongst the small number of students although many Polish families lived in the capital of Saxony.[7] The many local migrants, who also included Józef Ignacy Kraszewski [8] might have provided him with the decisive reason for choosing the city that was powerfully linked with Polish history and culture.[9] The extant work Stacja pocztowa (Post Coach in the City, Ill. 5) [10] also dates back to this time.

In Dresden Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (Ill. 6) had the opportunity of acquainting himself with major European paintings. He saw works by Rubens, Rembrandt and Dürer. As a student he spent many hours copying the works of Masters in the rooms of the Zwinger Gallery. Here he often found himself in the company of his fellow student Vaclav Brožik, who was equally disinclined to study at the Academy and later became a history painter.[11] Wierusz-Kowalski’s friendship with the Czech student had a great influence on his life. In December 1872 the two young men went on an excursion to Prague. Their journey of exploration was so promising that they left Dresden for good in winter 1873 and moved to the city on the Vltava. Here they spent about six months in the circle of young Czech artist friends, including František Ženišek and Josef Myslbec.[12] Brožik matriculated at the Art Academy and his Polish friend began working independently. He created small genre scenes (Ill. 7), which he exhibited and sold in Nikolaus Lehmann’s renowned art salon in Prague.[13] The artist’s early independence and his first financial successes had an effect on his future decisions.

In early summer Wierusz-Kowalski and Brožik decided to move to Munich together. Both of them registered at the Art Academy there and began their studies in August, the former under Alexander Wagner and the latter under Karl Piloty. One year later the two young men decided to go their separate ways. Brožik moved to Paris, whereas Wierusz-Kowalski was to remain for ever in the Bavarian capital.

1873 was the year in which the Polish artist made his international debut. His work Powrót kwestarza [The Return of the Donation Gatherer] (Ill. 8) was exhibited in the General Permanent Exhibition in Vienna.[14] It is difficult to call this work significant although it contains characteristic elements of the mature work of the painter, for example local customs and local landscape genre themes, the atmosphere of the motif, the shortening of perspectives, the large built-up group of figures in the foreground, the removed and synthetically expressed second background tiered behind further backgrounds, the spare and harmonious use of colours and the skilful accentuation of the colours. To this extent the painting Powrót kwestarza – it was surely made before he began his studies at the Munich Academy of Arts – indicates the artist’s talent and announces his career.

Wierusz-Kowalski studied for roughly one and a half years in Wagner’s workshop, which was very popular amongst Polish students.[15] This was also the period in which Józef Brandt[16] trained (he was a few years older). Brandt’s works influenced the works made by Wierusz-Kowalski as a student: Zaloty [Courtships] (Ill. 9)[17] and Na zwiadach (On the Outposts, Ill. 10) [18].

The young artist’s early years in Munich were a period of artistic self-discovery. Like many other contemporaries he was temporarily fascinated by the works of Maksymilian Gierymski .[19] Taking him as an example, he painted hunting and riding scenes in elegant 18th-century costumes (Ill. 11), thus in the so-called “late rococo style”, and scenes against the background of small Polish towns (Ill. 12). He used a now missing picture by Gierymski as an inspiration for his painting Wypadek w podróży [Travel Mishap] (Ill. 13).[20] Late rococo style paintings made until the end of the 1970s were fascinating on account of their use of delicate light in the early Autumn landscapes featuring elegant riders in red jackets on lean horses amongst pale golden groves of birch trees and sniffing hunting dogs. But gradually the artist liberated himself from this type of portrait and around 1880 he began to take an interest in motifs from the distant Caucasus. The new protagonists in his pictures were riders crossing rocky mountain landscapes. This had something to do with the war in the Caucasus that was closely followed in Europe.[21] Józef Brandt’s workshop contained a remarkable collection of weaponry, uniforms, traditional costumes and weapons used by Caucasian warriors, which had once belonged to the painter Theodor Horschelt. Wierusz-Kowalski used these exhibits for his pictures featuring Circassian themes (Ill. 14). In this connection the photographic estate of the painter’s family contains pictures of persons modelling as Cossacks. Independent of this, during this time and similar to his work in Prague, Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski painted simple, moving genre scenes in the spirit of Biedermeier, many of which were reproduced in the Polish press. Furthermore he continually took up motifs from the January Uprising, now and later (Ill. 15).[22]

In the second half of the 1970s Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (Ill. 16) started a family. He married Jadwiga (Ill. 17), the daughter of the writer and journalist, Wacław Szymanowski. His well-known father-in-law had a lot of connections. In this respect he proved to be a great support in helping the artist to rapidly develop his career, although many people held this against the artist. The young couple decided to settle in Munich. Children were born into the world (Ill. 18), and with every new arrival the family moved into a larger apartment.[23] The growing workshop, well furnished and filled with pictures and artists utensils, was not only a place of work: the artist also used it to present his own works to visiting collectors, art merchants and purchasers. The Wierusz-Kowalski’s had an open house that was regularly visited by young people whom the artist was only too ready to help. In 1885 Olga Boznańska arrived in Munich with a written recommendation. As a token of gratitude for his help she made a portrait of his son Czesław in her second apartment in Paris, where Czesław was studying at the time.

At the start of the 1980s Wierusz-Kowalski’s pictures began to feature winter scenes with huntsmen setting out with their dogs, coaches and sleighs on snow-covered paths, not to speak of aggressive wolves. During this time he completed the paintings Wyprawa na niedźwiedzia [Bear Hunt] (Ill. 19) and Napad wilków (Attacked by Wolves, Ill. 20).[24] Although these subjects were not the main motifs in his work they made the artist hugely famous.[25] Above all his paintings are associated with dramatic attacks by wolves, whereas the pictures are neither cruel nor shocking since they neither show blood nor death.

Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski was a master at painting snow (Ill. 21, 22). In his paintings it ripples in many nuances on a frosty morning, takes on a purple glow in the light of the setting sun, whereas it breaks up under the hooves of horses during cloudy days of thaw when the grey skies are mirrored in the drops of water. In other pictures white powdery snow gently covers the hillsides or lies heavy on the branches of bushes. Light reflections alternate with deep shadows, there are contrasts between warm and cool tones, and also special techniques like harsh glaring colours, pasty applications and the generous sweep of the freely led brush: styles that the artist used in order to catch the uneven texture of the snow reacting sensitively to every change in temperature and the movement of the wind.

Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski’s typical painting characteristics began to set in at the start of the 1880s. His favourite themes drew on Polish customs and landscapes. Most of the scenes he portrays are set in villages, and a few in small towns. Here the emphasis is not so much on the work and toil of everyday life but rather on the leisure activities of the rural aristocracy: hunting expeditions, people returning from fairs and sleigh rides, and always in movement, in different weather conditions, times of day and seasons of the year. His protagonists seem to float in an interim time and space, free from the duties and burdens of everyday life.

The artist placed large groups of figures in the foreground, mostly dynamic and set in powerfully short perspectives in diagonally running compositions. Other figures often appeared in the background, as recognisable variations to the main group (say, another sleigh ride, or a horse and cart with villagers), in order to emphasise the depths of the motif and sharpen the viewer’s subjective perceptions of time and space. His range of colours was harmonically restricted to fine tonal gradations. The cleverly placed light reflections and colourful accentuations on the surface of the pictures drew the attention of viewers. The portraits were boisterous, full of energy and power, or – quite by contrast – extremely atmospheric and subdued (Ill. 23, 24).

Starting in 1883 Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski’s works were presented in most of the exhibitions that took place in Munich. His pictures also came to places like Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Brussels, Prague and the United States of America. Even in his early career he was a regular participant in exhibitions in Poland, especially in Kraków, Warsaw, Lviv and sporadically in other towns. By contrast his works were only seldom to be seen in Poland in the 1880s and 90s. Aggrieved by disparaging criticism and discouraged by a lack of sales interest he gave up trying to send his works there. Instead he collaborated with the best art salons in Munich: with the galleries Wimmer, Heinemann, Fleischmann and Hugo Helbing. All of these were young ambitious “enterprises” that presented exhibitions and published catalogues as well as having branches in European capitals and America. The collaboration guaranteed his artistic success.

Wierusz-Kowalski constantly promoted his artistic career. He developed his own style and supplied the market with popular motifs. In addition he worked for illustrated periodicals dedicated to social and artistic themes, which also printed woodcuts of his paintings. Publishing houses also printed photographs of his works in fine reproductions, various formats and large print runs. All the time he endeavoured to maintain a high social status, something that was necessary if he was to be given lucrative commissions. Even Prince Regent Luitpold purchased one of his pictures from a private collection of paintings.[26]

Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski was the recipient of many awards and honours. In 1883, on the occasion of an exhibition in the Glass Palace, he was awarded a medal for his picture Polish Post, which he completed in several versions (Ill. 25).[27] In 1892 he enjoyed a huge success with a gold medal for his painting Wilki. W lutym na Litwie (In February, Ill. 26).[28] The Neue Pinakothek, which had been given a portrait of the Minister Johann Freiherr von Lutz in 1889, purchased the prize-winning work.[29] In 1890 the artist was awarded the title of Honorary Professor at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. In 1894 the Bavarian Ministry awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross of St Michael, fourth class. He also received medals and honours in Vienna, Lviv, Berlin and St Louis, as well as being invited to serve on juries in international art exhibitions in Munich and Berlin.

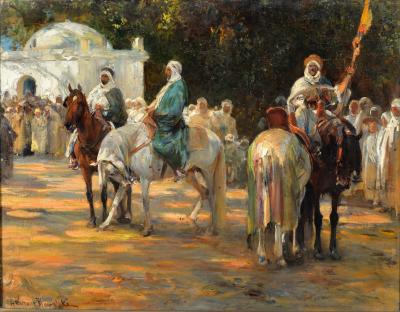

However, he was unable to maintain his successes in the course of time and failed to keep up with the changes in artistic developments. Worried by the dwindling interest in his work, in 1903 Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski set out on a brief trip to North America in search of new motifs and artistic inspiration (Ill. 27). That said, he did not succeed in fundamentally changing his artistic expression. During this time he completed a number of sketch-like pictures with abstract details and synthesised figures and objects. In doing so he turned to casual flat surfaces of colour, but such attempts failed to transcend the spirit of 19th century painting. His pictures continued to present galloping horses and processions of festively clad villagers on their way to church.

In 1910 he made another attempt to regain his dwindling popularity by preparing a panorama-like version of Attacked by Wolves (5 x 10 metres in size) for an exhibition: a work he had completed many years ago. He reckoned with a success and a sale of the work, whose sketches that had hung for many years in his workshop in Herzogstraße 15 (Ill. 28), and attracted enthusiastic reactions from both critics and visitors alike.

In the end he submitted to the feeling of his fading glory, unable to understand the changes taking place around him and occupied by the difficulties of his life, the expensive upkeep of an estate he had purchased in 1896 in Mikorzyn, near Konin, his growing children, his wife’s ailments and his own malaise.

After the outbreak of the First World War the family – the Wierusz-Kowalskis were subjects of the Russian Czar – was split up between fronts and borders. Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski died on 15th February 1915 and was buried at the Waldfriedhof in Munich.[30] His workshop was dissolved by the family and the circumstances of great difficulty. In April 1917 the pictures were sold at an auction in the Hugo Helbing Kunsthaus. His workshop equipment, the furniture, the easels and his remaining artistic estate and archive were taken to Poland. In Munich there remained only the memory and the pictures, witnesses to 40 years of masterly artistic work.

Eliza Ptaszyńska, May 2017