Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

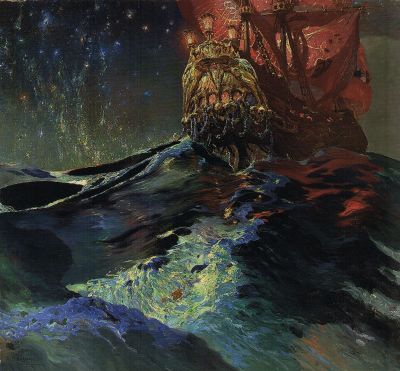

Visitors to “Polish Symbolism around 1900” may come with firm ideas, formed over the decades, about the pictorial world of “Symbolism in Europe”, to take the title of the early, important exhibition on this topic in 1975–1976 in Baden-Baden, Rotterdam (“Het symbolisme en Europa”), Brussels and Paris (“Le symbolisme en Europe”). If so, they will have to revise their view. As demonstrated by the paintings on show, the Polish version of this style covers a broad timespan from 1875 to 1918 and in some cases presents themes and a style of painting that would not be classified as “Symbolism” in Germany, France or Britain. At first, the strong presence of the historical painter Jan Matejko at the start of the exhibition is a surprise; only recently, in 2018–2019, were we introduced to him as one of the European “Malerfürsten” (“painter princes”) in the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, to a certain extent with the same paintings.[1] However in Munich, together with Wojciech Gerson, he represents the forerunners among the “Polish Symbolist” painters, who opposed historical painting and the political tendencies with which this style was associated.

In an exhibition on “European” Symbolism, therefore, one would be hard put to find some of the paintings shown in Munich: “A Japanese Woman” (1908, Fig. 10 . ) by Józef Pankiewicz, or the night-time view of the “Ludwig Bridge in Munich” (1896/97, Fig. 8 . ) by Aleksander Gierymski, or the Ukrainian woman lying in an open field, in the style of Franz von Lenbach, portrayed in “Indian Summer” (1875) by Józef Chełmoński (Fig. 7 . ), “Cloud” (1902, Fig. 13 . ) by Ferdynand Ruszczyc, which was influenced by Prince Eugene’s Swedish landscapes, the “Boy in School Uniform” (around 1890) by Olga Boznańska, which is reminiscent of Édouard Manet, or the folkloristic figure scenes (1891–1895) by Włodzimierz Tetmajer and Teodor Axentowicz (Figs. 21 . , 22 . ), to name just a few. The prefaces and introductory texts in the catalogue already indicate that the exhibition has something new to offer when they describe the “movement of the so-called ‘Young Poles’”[2] or the “first such comprehensive exhibition of painting by the Young Poles in Germany”[3], while at the same time making hardly any mention of Symbolism, if at all. We are not told whether “Polish Symbolism” and the art of the “Young Poles” are congruent, or whether one is part of the other. Indeed, no mention is made of either in the introductory text in the exhibition hall itself. As a result, a reference to older literature is required in the search for reliable definitions.

From a German perspective, Jost Hermand already described Symbolism in 1959 (and later in 1972) as a “late Romantic current, enriched with certain Impressionist elements” in painting immediately at the turn of the 20th century, in which “spiritistic-occultist elements” predominated with a “conscious antagonism towards positivist materialism”. Inspired by spiritualist secret societies and a tendency towards the “uncanny and inexplicable”, a “mysterious Symbolism” arose, whose adherents in Germany, influenced by the French artists Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Odilon Redon, Eugène Carrière and Gustave Moreau, the Belgian James Ensor and the early works of the Norwegian Edvard Munch, included above all Arnold Böcklin with his allegorical mythical creatures, the Munich artist Franz von Stuck and Max Klinger in his late works, Fernand Khnopff in Belgium and Giovanni Segantini in Italy. Their work was published from 1895 onwards in the Berlin art and literary magazine “Pan”.[4] Similarly, in 1965 (and in the second edition published in 1973), Hans H. Hofstätter described Symbolism as “art that is emphatic and aggressive anti-bourgeois, and sometimes even anti-ethical” with repeated attempts “to break through the positive realism of the bourgeois worldview and world order”.[5] He used the words “pessimism” and “perversion” to describe Symbolism’s aesthetic and used the words “cosmic Symbolism”, “death and eros”, “dream experience”, “the human as mask”, “symbolic forms of woman”, “fetishism” and “satanism” to describe its pictorial worlds.

[1] “Malerfürsten”, exhibition catalogue, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, catalogue concept: Doris Lehmann and Katharina Chrubasik, Munich: Hirmer 2018; see also the article in this portal, “Malerfürst” Jan Matejko in the Bundeskunsthalle https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/malerfuerst-jan-matejko-der-bundeskunsthalle

[2] Roger Diederen: Preface, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 8

[3] Barbara Schabowska: Greeting, ibid., page 11; similarly Albert Godetzky/Nerina Santorius: Introduction, ibid., page 14

[4] Symbolism chapter in: Richard Hamann/Jost Hermand: Stilkunst um 1900 (Epochen deutscher Kultur von 1870 bis zur Gegenwart, Volume 4 [1959, 1972]), Frankfurt/Main 1977, page 289–304

[5] Hans H. Hofstätter: Symbolismus und die Kunst der Jahrhundertwende. Voraussetzungen, Erscheinungsformen, Bedeutungen [1965], 2nd edition, Cologne 1973, page 9, 23