Poles in Germany. Roads to visibility

Mediathek Sorted

![„Pola Negri - unsterblich“ [‘Pola Negri - immortal’] „Pola Negri - unsterblich“ [‘Pola Negri - immortal’] - A film documentary about the life and work of one of Germany's greatest silent film stars of Polish origin. (German)](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/pola_negri_-_filmstill_2_0.jpg?itok=2xsBI27X)

„Pola Negri - unsterblich“ [‘Pola Negri - immortal’]

„Drei Tage im November. Józef Piłsudski und die polnische Unabhängigkeit 1918“

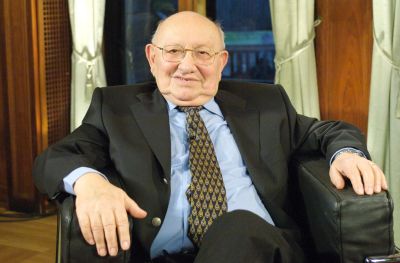

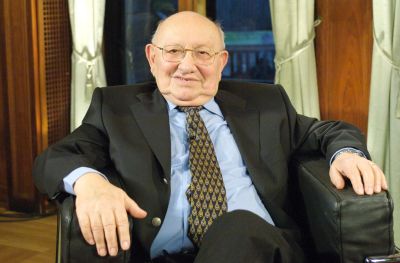

Artur Brauner - Ein Jahrhundertleben zwischen Polen und Deutschland

Teresa Nowakowski (101) im Gespräch mit Sohn Krzysztof, London 2019.

Karol Broniatowski's memorial to the deported Jews of Berlin

Film "The Madman and the Nun" - St. Ignacy Witkiewicz, Filmstudio Transform, Director: Janina Szarek

WORMHOLE, 2008

Interview with Leszek Zadlo

ZEITFLUG - Hamburg

Der Planet von Susanna Fels

![A film documentary about the life and work of one of Germany „Pola Negri - unsterblich“ [‘Pola Negri - immortal’] - A film documentary about the life and work of one of Germany](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/pola_negri_-_filmstill_2_0.jpg?itok=2xsBI27X)

Looking for work

The German Empire founded in 1871 offered its citizens equality of legal status, legal protection and free mobility within the borders of the Empire. Prussian Poland also made use of this: The influx of Polish-speaking citizens of the Empire into the industrial regions and mines of the Ruhrgebiet in the decades before the First World War – around 500,000 people – was, to that point, the largest compact migration of a non-German population in German history; it paved the way, so to speak, for all the economic migration that would later follow. But they were also migrating in a time in which, in the eyes of the nationalist parties and of some of the public, Poles, who were becoming the greatest enemies of the Empire, appeared to endanger the unity of the young country through their own national ambitions.

This mixture of cultural closeness and latent discrimination often resulted in Poles shying away from putting their Polish identity on show in predominantly German-speaking regions. Better not to speak Polish on the street, better not be conspicuous, better to quickly integrate into German society. The majority of children born to internal migrants learnt hardly any Polish. At the same time, these migrants were shaped not only by the Ruhr area society (in 1910 for example they represented a quarter of the population in Recklinghausen), but also by other emerging industrial centres, such as the large North German cities or Berlin. However, this group was in no way homogeneous: As well as the Catholic migrants, there was also a large migration of Protestant Masurians, particularly in Westphalia and, as well as the people from Poznań who spoke High Polish, Upper Silesians and Kashubians, with their characteristic dialects and languages, also moved there. The “Ruhr Poles” (westfalczycy), in particular, developed a rich life centred around clubs and associations, and Polish church structures, trade unions and political representation all sprang up.

In addition to the internal Polish migrants, Poles from abroad, from Austrian Galicia or from the regions annexed by Russia also arrived. At times, there were several hundred thousand of them working primarily as seasonal workers in farming, the so-called “Sachsengänger”.

Whilst this was almost exclusively a proletarian economic migration, representatives of the Polish elite also moved to Germany: As the capital, Berlin attracted representatives of the nobility (such as the Radziwiłł and Raczyński families), but Poles also had seats in the Reichstag and in the Prussian state parliament. At times, writers such as Adam Mickiewicz and Józef Ignacy Kraszewski chose to live in Dresden and students moved to the various universities of the Empire; some also had an academic career here. Not least, politicians in the Empire found a place to stay; the socialists Rosa Luxemburg and Julian Marchlewski were just two of many.

The “Munich School” was particularly well known in Poland. This term conceals the fact that between 1828 and the outbreak of the First World War more than three hundred Polish painters and sculptors were studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and in its surrounds. Even if this was not a “school” in the true sense of the word, various contacts and references developed among the many prominent painters, such as Józef Brandt, Jan Matejko, Aleksander Gierymski, Maksymilian Gierymski, Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski and Wojciech Kossak. In his role as court painter, Kossak is said to have later played an important role in the capital’s art scene. Female artists, such as Olga Boznańska, were also able to improve their skills in Munich, even if there were few females there as women were not allowed to study at the Munich Academy before 1920.