“MRR”: His Life

Mediathek Sorted

Interview with Gerhard Gnauck on SWR (German)

Interview with Gerhard Gnauck in memory of Marcel Reich-Ranicki (German)

In memory of Marcel Reich-Ranicki on Radio ‘Trójka’ (Polish)

Marcel Reich-Ranicki - Radio play by "COSMO Radio po polsku" in English

Marcel Reich-Ranicki in an interview with Joanna Skibińska

Marcel Reich-Ranicki auf Polnisch! Interview mit Joanna Skibińska 2000

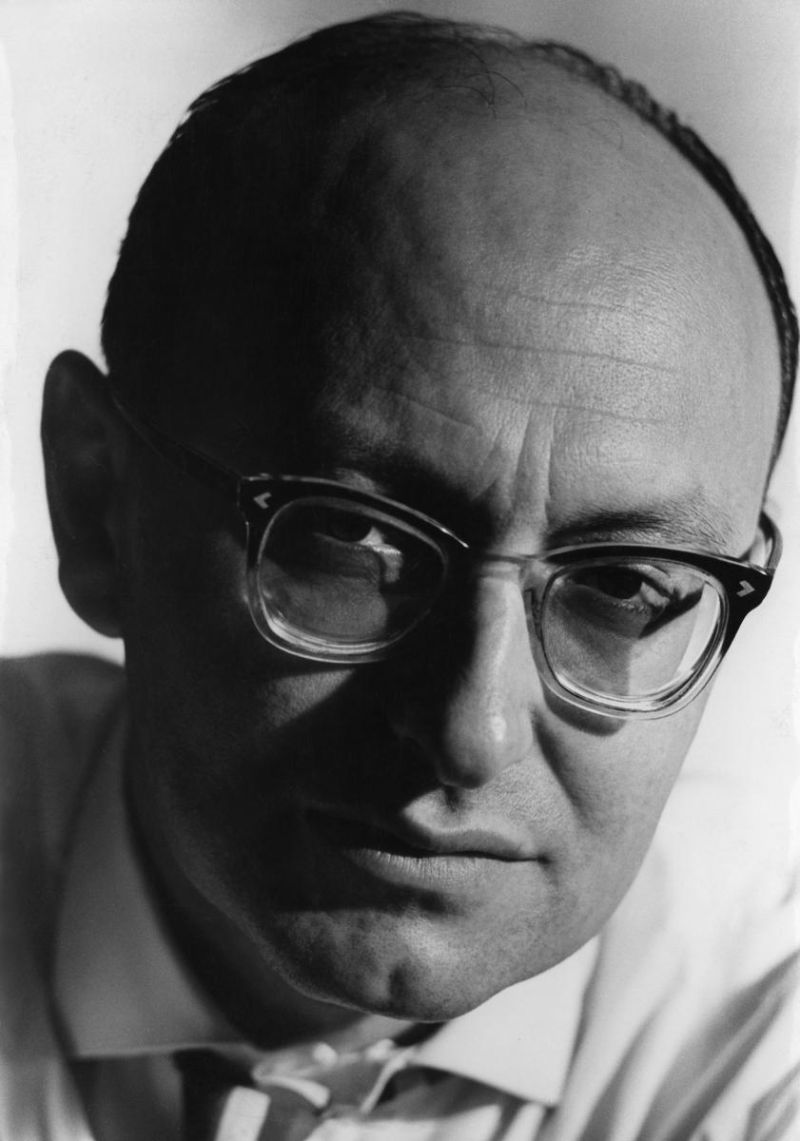

To begin with, a few sentences about Marcel Reich-Ranicki.

“MRR was/is the most influential literary critic of our time, even more important than Bernard Pivot in France.”

“MRR has made himself a reputation as a television star, comic hero and advertising promoter.”

“MRR is an icon of the arts pages.” (The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel)

When I decided to write a book about him a few other sentences came to my ears:

“You want to write about Reich-Ranicki?! He already has a halo.” (From a German publisher who finally decided not to print my book.)

“Reich-Ranicki?? When he dies, he will go directly to heaven.” (From another German publisher who also finally decided not to print my book.)

“Reich-Ranicki? Be careful. He’s both a showman and a Stasi man.” (A Polish historian.)

In the beginning a boy by the name of Marceli Reich was born on 2. June 1920 in the town of Włocławek on the Vistula. The times were turbulent. Having been partitioned for many years, Poland was finally an independent country once more and Włocławek (which had belonged to the Tsarist Empire until the First World War), was also liberated. But the peace did not hold for long. In summer 1920 the Red Army was already on its way westwards. It was in the middle of Poland and wanted to reach Berlin within a few weeks as the vanguard of the world revolution. A cavalry division stood on the eastern bank of the Vistula at a bridge leading to the town centre in Włocławek. If the troops had succeeded in crossing the river the history of Europe would probably have been completely different.

At the very last moment the bridge was blown up and the life of the Jewish family, Reich, who had fled the town as a precautionary measure, continued on its peaceful path. His father was a pious man, an entrepreneur by profession. He spoke Polish, Russian, Yiddish and German. By contrast his mother, who felt close ties to German culture, spoke German very well but her Polish was very poor. In his autobiography[1] Reich-Ranicki never revealed which of the languages was the family “business language”. But he did confide to me the following information: “There were two business languages: Polish and German. My mother and father spoke German when they did not want the children to understand what they were saying. At the time we could speak Polish better than German.”[2] Marceli had two older siblings, Gerda and Herbert Aleksander.

In 1929, plagued by business failures, the family moved to live with relations in Berlin. Here Marceli attended the Fichte grammar school, after which he began a professional training. (Because of his Jewish origins he was banned from studying in a university). In the mid-30s his parents and brother moved back to Warsaw, where Herbert Aleksander opened a dental practice. Gerda succeeded in emigrating to England with her husband. Marceli remained in Berlin – and at the end of October 1938, following the so-called “Polish action”, the German authorities expelled him to Poland against his will, along with around 17,000 other Polish Jews.

The 18-year-old Marceli Reich made his way to Warsaw and from then on he lived with his parents. He later described this period in his life as being not very happy. But scarcely anyone imagined what might follow. One year later German troops occupied Poland. The young, unemployed Reich witnessed the air raids and the brutal treatment of the civilian population, especially the Jews. The family remained in Warsaw. When the ghetto was erected, Złota street, where they lived was the first street outside the ghetto wall. (The apartment in house number 43 was situated between today’s Palace of Culture and the central station; the row of houses no longer exists). Hence the family were forced to live in the ghetto.

Marceli’s first contact with the “Jewish Council” (the administrative body of the ghetto, which was of course in the hands of the German occupying authorities) was when he worked as a translator on the census of the Jews in the city. At the end of the census he was even the head of the “translation and correspondence office”. At the same time he wrote the first reviews in his life – as a music critic for concerts. He wrote under the pseudonym “Wiktor Hart” for the Gazeta Żydowska (Jewish Newspaper), that was published in the ghetto. He was both a witness and a translator when the SS boss in the Jewish Council announced the order to liquidate the ghetto.

The poet, Antoni Marianowicz, who was also an inhabitant in the ghetto, later wrote that at the time he had seen Reich walking around in a cap belonging to the (Jewish) ghetto police. But we only know for sure that he worked in the Jewish Council. During the later Communist regime in Poland Reich was considered a collaborator, something which he was continually forced to justify. It is clear that, given the tragic fate of the Jews in occupied Poland, such accusations were unjust.

At the start of 1943, when many people, including Reich’s parents, were transported to an unknown destination (the extermination camp in Treblinka), Marceli decided to flee. He married Teofila (“Tosia”) Langnas, whom he had got to know in the ghetto in 1940, and both fled to the “Aryan side” of the wall, as it was known. This was the start of an odyssey from hiding place to hiding place. Their situation improved when Marceli – and sometime later also Tosia – found a hideout with the family of a typesetter by the name of Bolek Gawin in a tiny two room house in Osada Ojców Street on the edge of the city. Reich later wrote that he entertained his “landlords” by recounting stories from novels. Barbara Rochowska, the family daughter, still has vivid memories of the Reichs. In 2006 Bolek and Eugenia Gawin were posthumously honoured and decorated as “Righteous among the Nations” by the Yad Vashem memorial centre.

The Reichs remained with the Gawins until autumn 1944 when the Red Army conquered the suburb. The Reichs no longer feared for their lives. Instead they wanted to be of use to the Polish state, even after it had disappeared once more from the face of the earth in 1939. They moved towards Lublin, where the new Communist dominated government was being put together. The new organs of security were also being trained there. The Reichs found employment at the “Department (later Ministry) of Public Security” (MBP). Marceli was initially a translator, primarily responsible for military censorship, i.e. censoring postal communication.

Nothing is known about the month in which the Reichs were living in Lublin. The first trace of their life was found at the start of February 1945 in the (surviving) files of the Ministry of Security. Marceli Reich was delegated to Upper Silesia as the chief of the Ministry’s “operation group” there. Here he said that his job was to organise censorship. But he was soon moved back to the capital, Warsaw. After some assiduous work in the MBP he was sent to Berlin on another sensitive mission at the start of 1946.

In his autobiography Marceli Reich only writes a single sentence on his work there. Otherwise he gives us many details about the theatre life in Berlin and his return to the city of his youth. Here two Polish files provide further help. At the time Reich had the rank of a lieutenant, and was officially employed at the Polish “Office for Restitution and War Reparations” (BRiOW). He covered the length and breadth of Berlin trying to track down the goods and industrial sites that had been robbed by the German occupying forces, before sending them back to Poland. His office was situated at 42 Schlüterstraße in Charlottenburg in a building belonging to the Polish military mission.

That said, documents in the files of the Ministry of Security - they are now managed by the IPN authorities – imply that Reich had another unofficial duty. An unnamed man in the Berlin office wrote reports – they were described as “characterisations”, tantamount to denunciations – about Reich’s closest colleagues. The codename “Platon” was written under every report (Polish: raport). Many details lead us suppose that the man who was spying on his colleagues was Marceli Reich. Many decades later Reich-Ranicki categorically refused to answer my spoken and written questions on the theme.[3]

The months in Berlin left deep marks on Reich’s memory. He bore witness to this in 1958 in his only piece of literature, a tale entitled “A Very Sentimental Story”. Here he describes how a young Polish lieutenant climbs into a large car in Berlin driven by a German chauffeur. He wants to go to the Deutsches Theater to see a performance of “Hamlet”. The story continues:

“After the performance he wants to be alone. The actors are playing a play that always arouses his emotions. It is the story of a young intellectual who has the bad luck to be living in a totalitarian state, and who rises up against all those around him and is ground down. It is an “exemplary police state – everyone is spied on by everyone.”[4]

In April he returned to his headquarters, the MBP building in Warsaw (now the seat of the Ministry of Justice). Reich was given ever greater responsibilities. For a time he was the head of the secret service responsible for Germany, and then for Great Britain. At the start of 1948 he was sent to London on his hitherto most important job abroad. The Cold War had begun, London was not only the capital of the then strongest military power in the Western world, but also the major city for Polish exiles and the headquarters of the (non-Communist) exile government.

However, during preparations for the new job he was told that it would be impossible for him to represent Poland with the name “Reich”. As with several Jews in post-war Poland, above all those who worked in the Party or for the State, Reich gave himself a “Polish sounding” name that was more than just a pseudonym. From now on the name in his passport was Marceli Ranicki. Years later he said that he had accidentally got to know a girl by the same name. This was possibly a young colleague called Janina Ranicka who worked in the censorship office for foreign postal communications.

This time it was crystal clear that Ranicki would have two main duties in London. He was to be the Resident, i.e. the top Polish secret service agent in the whole of Great Britain: and because he was a “legend” he was also given a job in the Foreign Ministry with whose deatils he had to acquaint himself as quickly as possible. Thus Mr. Ranicki was initially a Vice-Consul and later the Consul and Head of the Polish consulate general. At the age of 28 he was the youngest diplomat in London with such a rank.

Alongside his everyday consular duties Ranicki worked on other jobs for the Security Ministry. In his autobiography, he tries to play them down in an amusing manner: “I have neither a false beard nor a toupee.” He also had “no contacts whatsoever with exile Poles.“ Nonetheless he does not deny that he employed “10 to 15 members of staff, most of whom were jobless or pensioned journalists”, who informed him (and therefore Warsaw) “regularly about Polish emigrants”. [5]

To tell the whole truth, it must also be stated that Ranicki kept a file on over 2,100 Poles living in Great Britain. Spying on the leading opposition politician, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, was a matter for the boss – Ranicki himself. He had regular meetings with Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz, the publicist who was later to become prime minister of the government-in-exile, on a bench in Waterloo Park, where he was unsuccessful in trying to recruit him to work for “security”. The idea was to reward Cat-Mackiewicz for his collaboration by allowing him to return to Poland.

The first person to make public Ranicki’s work for the Ministry of Security, (in 1991), was his one-time assistant in London, Krzysztof Starzyński, who changed sides in 1950 and remained in the West. Ranicki has often been faced with accusations that he helped to “move home” Polish immigrants and members of the Armed Forces, who were then thrown into prison in Communist Poland – or whose fate was even worse. That said, there is no concrete evidence to support these accusations. After 1989 Reich-Ranicki justified his actions by saying that he had “believed in Communism at the time”. He did not regret his actions.[6]

At the end of 1949 Consul Ranicki was suddenly ordered back to Warsaw. Sometime later he was thrown out of the MBP, the Foreign Ministry and the Communist Party of which he was a member. Had this something to do with the growing anti-Semitism in the Polish apparatus – as Ranicki later hinted? Or was it more to do with the ideological alienation between him and the Party? Nothing can be established for sure, but the files do reveal that Ranicki’s London office with its staff and agents had almost completely collapsed (partly because people were changing sides), and this had raised alarm bells with the Head of Security in Warsaw.

Ranicki writes that, out of loyalty, he saw it as a “decent act of duty”[7] to return to Poland. But he does not say whether he meant loyalty to the country of his origin or to the ruling system or another instance. The only thing certain is that he did not ask to be recalled “for political reasons”[8], something he later claimed in order to put himself near to the ranks of dissidents and human rights activists.

Nonetheless his fall was painful; Ranicki had to spend two weeks in prison. After that he and his wife Teofila and son Andrew who had been born in London – were free once again, as free as was possible in Poland during the Stalin era. And in the prison cell, where he was at least allowed to read German literature, a new Ranicki was born: the literary critic.

Ranicki gradually made a name for himself as an expert on German literature, a field which was not exactly popular in Poland after 1945. He wrote innumerable articles that were published in journals ranging from the village newspaper “Wieś”, via cultural periodicals all the way to the organ of the Party, the “Trybuna Ludu”. In the 1950s he also received visits from authors, first Brecht from East Germany, then Böll and Grass from the Federal Republic. For them Ranicki was the ideal contact And he got to know them all. But he was also acquainted with many of the most famous Polish writers (Lec, Tuwim). After a brief study visit to the Federal Republic Ranicki applied once more for a German visa for himself in 1958, and, in order to trick the authorities, he also simultaneously applied for a British visa for his wife and son. The plan was successful. Once they were all in the West, they remained there.

He now began his third career, after the MBP and his cultural work in Poland. First of all he changed his name to “Reich-Ranicki“, after an editor on the F.A.Z. advised him to turn his two names into a single name. He began his career as a critic on the F.A.Z., before moving to Hamburg to work for Die Zeit. Later he moved back to the F.A.Z. and was also the main critic in the ZDF programme, Literarisches Quartett from 1988 to 2001. By now he had become known as “the Pope of German Literature”. Very early on he allied himself with the most important group of German-language writers, the Gruppe 47.

But he never entirely cut himself loose from Poland. In his first years in Germany, after 1958, he regularly wrote about Polish literature and his articles were later turned into a book. [9] Marcel Reich-Ranicki also maintained his contacts with a few Polish and Polish-Jewish emigrants, as well as with intellectuals who arrived from Poland, like Szczypiorski. That said, neither he nor his wife - at least until 2009 - and son ever returned to Poland despite the many invitations, one of which was from the State President, Aleksander Kwaśniewski.

Poland too never entirely cut itself off from its former citizen. The regime accused him of contacts with the worst “antisocialist elements” in Polish exile. Reich-Ranicki’s Warsaw colleague from the 1950s, the German scholar and theatre academic, Andrzej Wirth, was commissioned to use his journeys to the Federal Republic in order to “spy out Ranicki’s private life and his material situation in Germany”.[10] Having agreed to this, he met up with Reich-Ranicki, but delivered nothing of any value to the authorities in Poland. The Polish secret service gradually became convinced that Wirth, (codename “Bruno”) was only reluctantly working for them and stopped working with him.

This article has mainly covered the Polish and Jewish aspects of Reich-Ranicki’s life. The German part of his life is comprehensively dealt with in the biographies written by Thomas Anz and Uwe Wittstock, as well as in a richly illustrated book by Frank Schirrmacher. Teofila Reich-Ranicki died in 2011, to be followed two years later by her husband, Marcel. They were both buried in the main cemetery in Frankfurt-am-Main (Urnenhain, Gewann XIV 34 UG).

Speaking about himself, Reich-Ranicki once said that his fatherland was “literature, German literature”. He did not wish to remain in people’s memory as “50% Polish, 50% German and 100% Jew“, a sentence from the 1950s which he later denied ever saying. In any case he was never a true Jew in the religious sense of the world, but a self-confessed atheist. If anything connected him to Poland, he wrote, then it was the language, its poetry and Chopin. And a city. He said that he left the land of his birth in 1958 in a wistful mood. “It was not difficult to leave Poland, but to leave Warsaw. Here, for almost 20 years, I lived through an infinite number of experiences, burdens, suffering and love.” [11]

Gerhard Gnauck, April 2017

Further reading:

Gerhard Gnauck: Wolke und Weide. Marcel Reich-Ranickis polnische Jahre, Stuttgart 2009

For further information: http://www.maths.ed.ac.uk/~aar/surgery/bio.htm

Here you can will find the entry about Marcel Reich-Ranicki in the Encyclopaedia Polonica.