Karol Broniatowski – Gouache paintings

Mediathek Sorted

In this respect another work gives us a much stronger statement. The feeling of terror that is linked with the consciousness of the irreversibility of fate is expressed in the memorial he created at Grunewald station.[2] It resulted from an unexpected approach to his sculptural work based on his desire to create a “figure” and simultaneously to endow it with a suggestion of non-fleshiness. Given these preconditions the artist succeeded in creating a reverse perspective of time by grasping human shapes in the manner of a negative photo. The 20 metre long wall of hollow silhouettes literally disappear into thin air, lose their weight and fleshiness like people who become their own shadows as soon as they find themselves on the ramp.

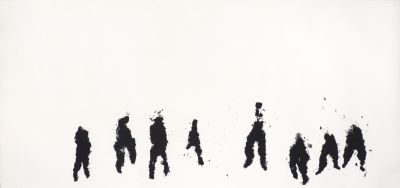

Drawings and sketches were part of the work on the memorial: at sometime or other they were liberated from their helpful function and changed into an ordered series. Almost all of them portray human silhouettes drawn with Indian ink on huge cardboard boxes, which are reminiscent of the hollowed out negative figures in the wall of the memorial and remind us in the conventional sense rather of positive photographic prints. For this reason we perceive them in the categories of the dialectic of spirit and fleshiness, memory and oblivion, life and death. In the course of time however, the material began to thicken and take on juiciness and colours. Alongside the clearly eschatological threads there also emerges a reflection on the past, about art and culture, what remains of people. The series of gouache paintings is a clear link to ancient classical culture; the centaur, a symbol of vitality and potency resulting from the unification of human and animal features, i.e. from purely biological characteristics. Portraits of animals in Palaeolithic rock paintings in the caves of Western Europe have a similar expression. In Broniatowski’s works the subtle links with the earliest period of creative activities are expressed not only in the mythological figure of the centaur but also in his use of a rusty red reminiscent of the natural pigments that were used in Altamira, Lascaux and Gragas. The “rudimentary“, fuzzy outlines of the silhouettes painted in red look like excerpts of living bodies reminiscent not only of the hand-painted portraits in Altamira and Gargas but also of the ultramarine blue silhouettes in the pictures of Yves Klein, which are type of modern Vera Icon, a portrait of real registered fleshiness caught in motion on the canvas. This is nothing other than an attempt to capture an accidental momentum, to pin down a fleeting “flesh” situation that is simultaneously subject to change. The consciousness of impermanence also arises when we are faced with the female coquetry indicating the category of vanitas, that can be found in European art over the past thousand years.

The drawings and gouache paintings are therefore a natural and inalienable complement to Karol Broniatowski’s sculptural work. Only thanks to them can we see his creative path – from his debut to the present day – as a logical, unbroken whole. It is not simply based on reflections on form and the way in which figures function in art, but is above all a grappling with the crumbly nature of human flesh resulting from the war trauma his generation inherited from their parents.

Anda Rottenberg, November 2017

[2] „Mahnmal für die deportierten Juden Berlins am Bahnhof Grunewald“, 1991.