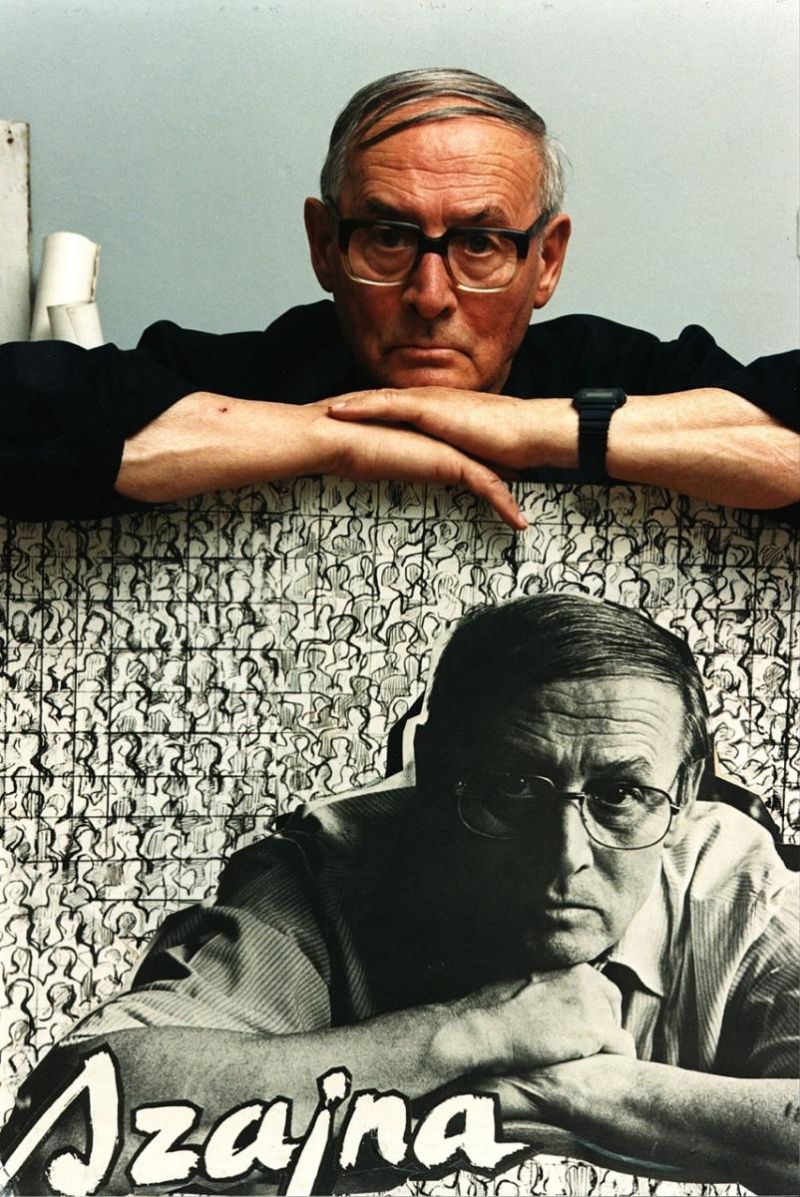

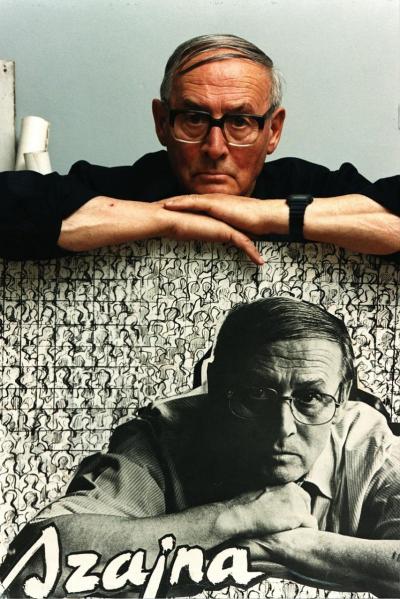

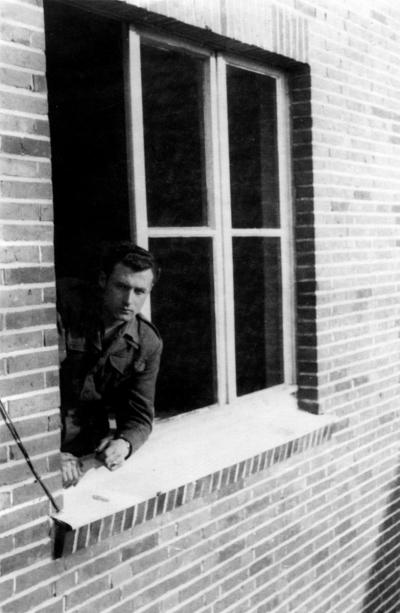

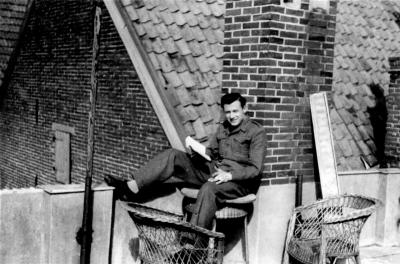

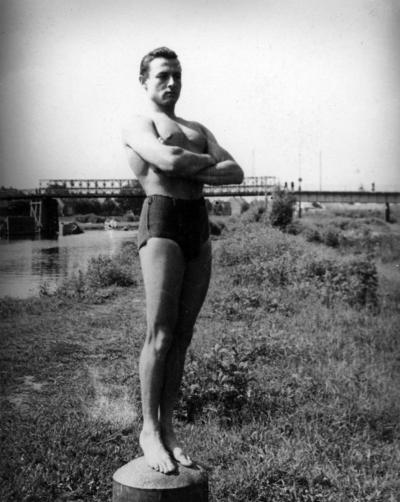

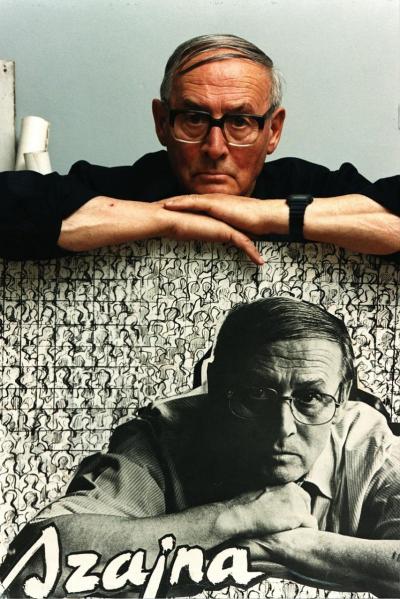

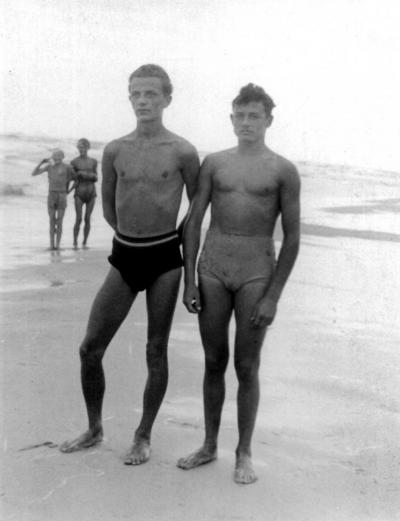

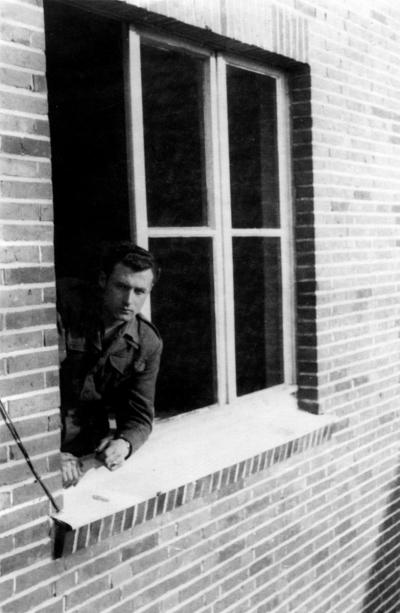

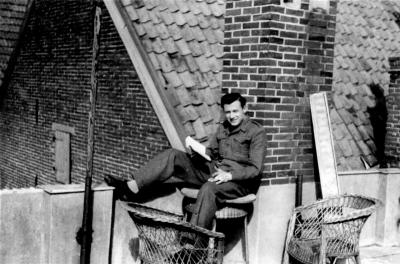

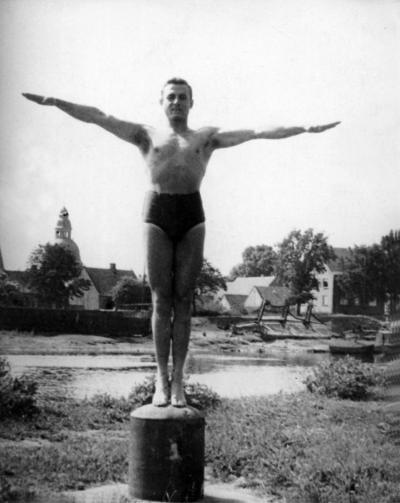

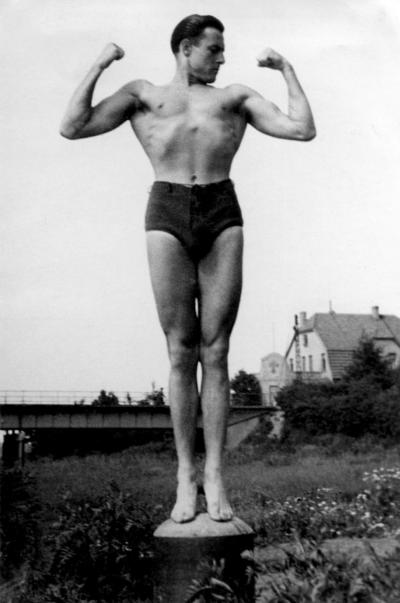

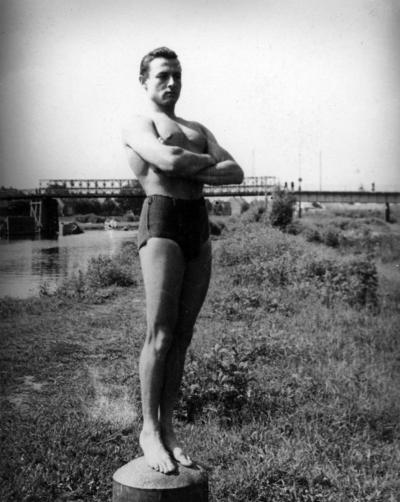

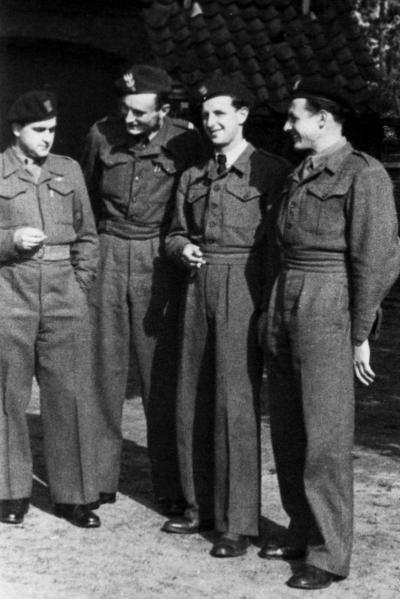

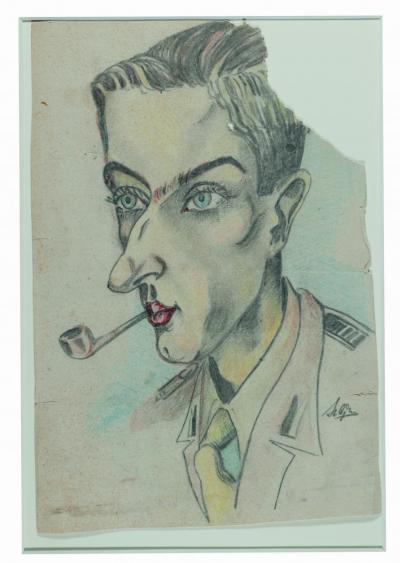

Józef Szajna in Maczków

Mediathek Sorted

Józef Szajna - Hörspiel von "COSMO Radio po polsku" auf Deutsch

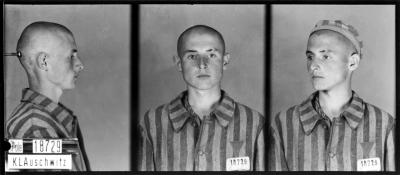

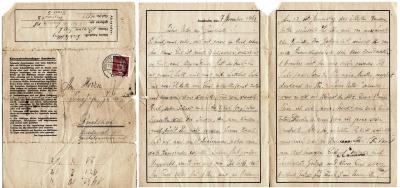

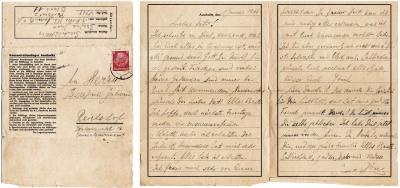

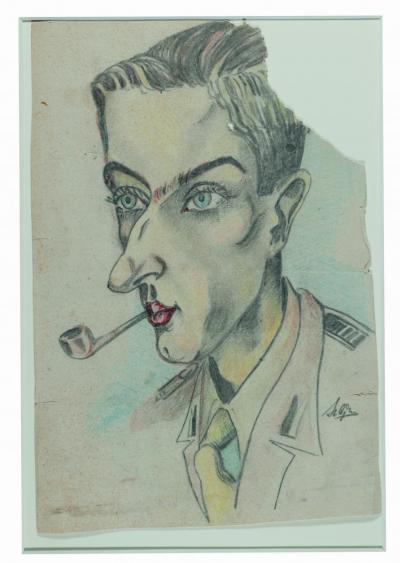

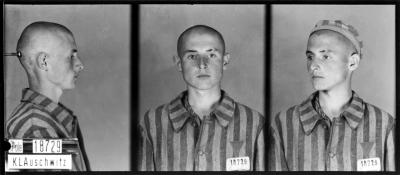

In winter 1944 he was transferred to the concentration camp in Buchenwald, and taken to the external camp in Schönebeck near Magdeburg. Here he made his first wall paintings using the burnt ends of matches. On 15th April 1945 he managed to flee from a death march ordered by the camp commanders.

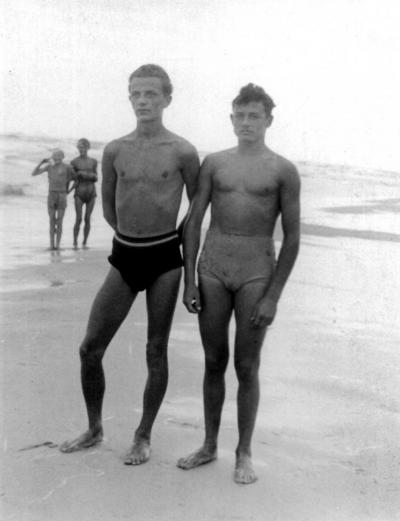

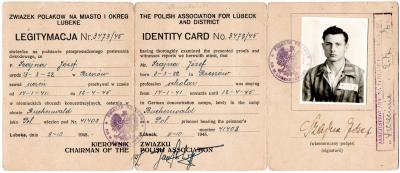

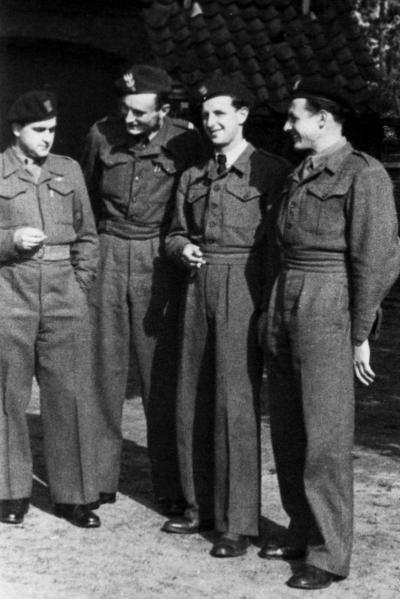

Immediately after the liberation he considered returning to Poland, but before that he wanted to complete his A-levels. Such an enterprise seemed impossible in his home country that had been destroyed. When he learned of the existence of a town called Maczków on the Ems, a Polish enclave in the north-east of Germany, he decided to make his way there.

Here he stayed for over two years, and here he was able to experience the one thing that the majority of Poles in Germany yearned for after the Second World War: the breath of freedom, a feeling that was only too understandable after the years of deprivation, cruelty and absurdities of the war that the Germans had started. Perhaps also because it was impossible to foresee a free Poland in the post-war European order. The consequences of this new order were all too clear for the Polish forced labourers, prisoners of war, concentration camp prisoners and members of the Allied combat units, when the country was divided into three parts. There was no longer any free homeland to return to and the accompanying dilemma of whether to return or remain in emigration inevitably led to inner conflicts.

Given these preconditions it was a small miracle that word quickly spread amongst the Poles in Germany about Haren on the Ems. Indeed it only took a few months for the town to take on the character of a legend. In April 1945 the British Allied authorities decided to evacuate the town entirely and hand it over to Poles who were stranded in the region. The 3,000 original inhabitants were given only a short time to pack their belongings before most of them were housed in farmhouses in the surrounding countryside. Around 5,000 Poles then moved into their houses and apartments. The majority of them were soldiers – both men and women – who had met up under dramatic circumstances in the nearby prisoner of war camp in Oberlangen. More than 1,700 people who had participated in the Warsaw uprising in August/September 1944 had been held prisoners there as ex-soldiers and officers. The majority of these were girls and women who had fought against the Germans by working in the areas of communication and nursing. Many of them had falsified their birth dates in order to be treated as adults and enable them to take part in the uprising. After its brutal repression, the mass execution of the rebels and the civilian population, along with the hitherto unheard of annihilation of the Polish capital, they were deported to the Emsland. The forged birth dates proved to be a blessing, for the Germans did not recognise minors as combatants, and would otherwise have sent them directly to the concentration camps.