Hermann Scheipers

Mediathek Sorted

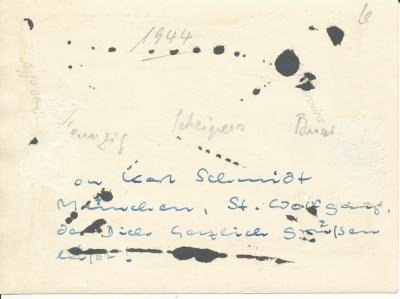

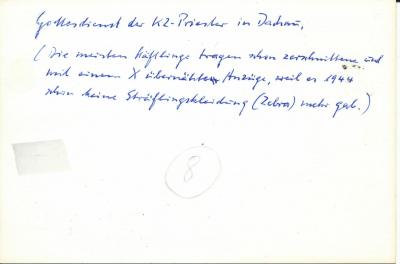

![The rear side of the photo of the church service for priests in the Dachau concentration camp The rear side of the photo of the church service for priests in the Dachau concentration camp - With a handwritten remark by Scheipers: "Church service of the concentration camp priests in Dachau (Most of the prisoners are already wearing suits that have been cut up and sewn over with the X, because by 1944 there were no more prisoner clothes [...]"](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/013b_-_rueckseite.jpg?itok=Il_qnB9A)

Dir gehört mein Leben (DE)

I owe you my life (EN)

Moje życie należy do ciebie (PL)

Conversation with Jacek Barski

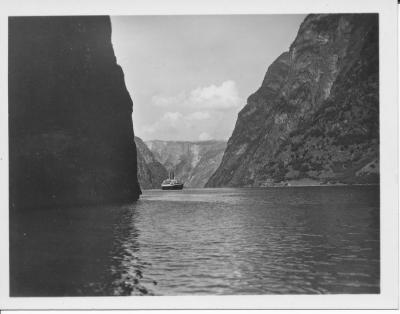

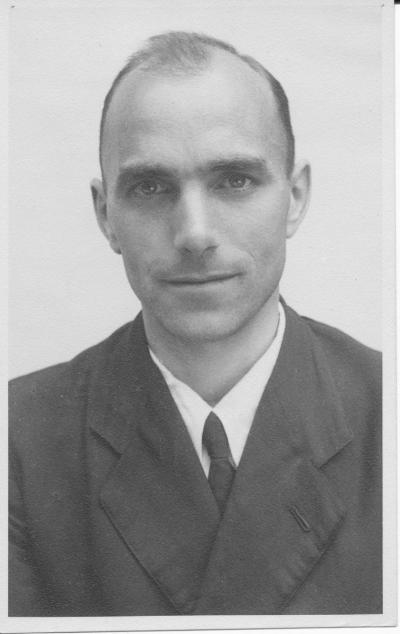

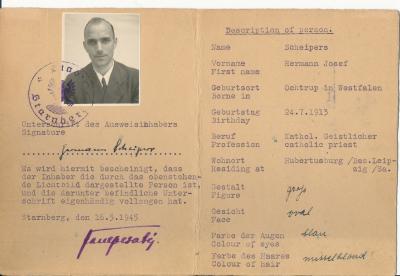

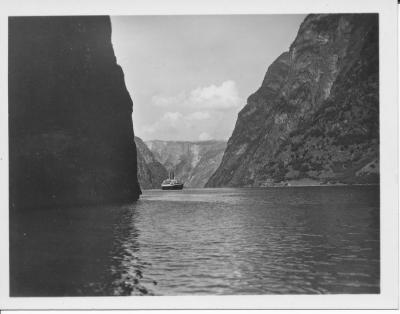

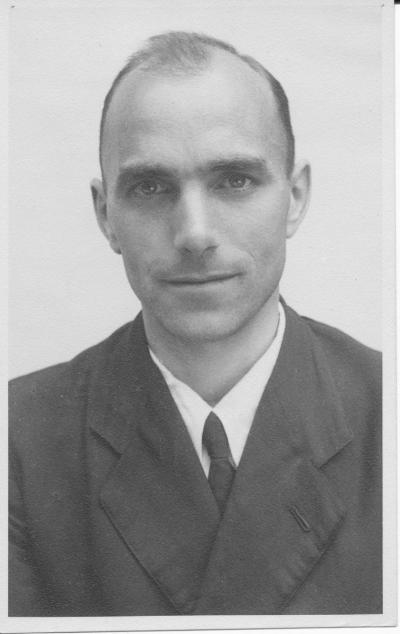

When I suggested the idea of publishing a lot of photos from his private collection on the Porta Polonica website, Hermann Scheipers replied in flawless Polish “W porządku!” (“That’s fine!”). Hermann Scheipers is a Catholic priest who will be 102 on 24th July 2015. There is not the slightest doubt that he is held in veneration by Polish people living in Germany. In 1940 he was thrown into prison for his exemplary commitment to the welfare of Polish forced labourers. Not long afterwards he was sent to the concentration camp in Dachau where he narrowly escaped the gas chamber thanks to the help of his twin sister Anna.

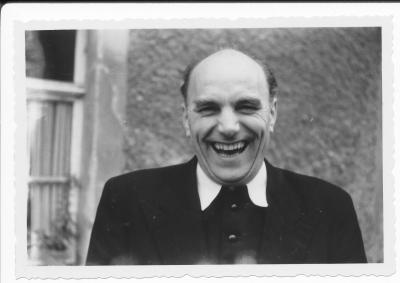

And today I am talking to him in Ochtrup (Westphalia), where he now lives, to hear once more the incredible stations of his life and his suffering under two German dictatorships. My immediate impression is that Scheipers is only too willing to speak about his experiences. Although his voice is rather shaky he still exudes the power, conviction and self-confidence that surely helped him survive the monstrous conditions in the concentration camp, and even to endure the death march after the camp was evacuated in 1945. (For more, see the conversation in the mediatheque between Hermann Scheipers and Jacek Barski on 12th May 2015 in Ochtrup).

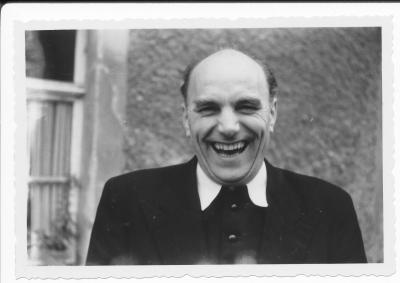

Hermann Scheipers is a man of action, bursting with ideas. And a man of faith. You can see this simply from the photos of him that go back a complete century. His appearance is full of charisma, inner conviction, single-mindedness and tenacity. His mystifying smile, even on the photos from his time in a concentration camp, radiates confidence, joy and an active Christian belief that faith knows no fear.

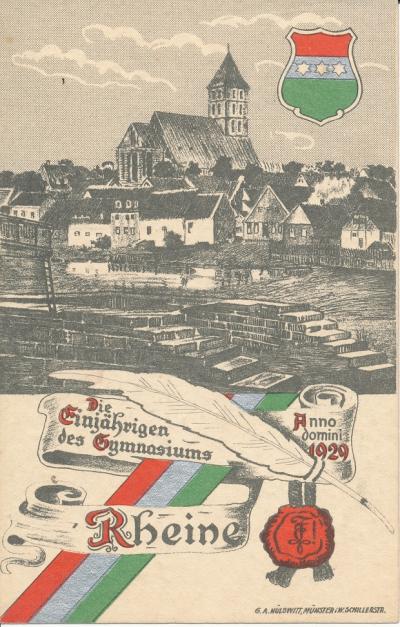

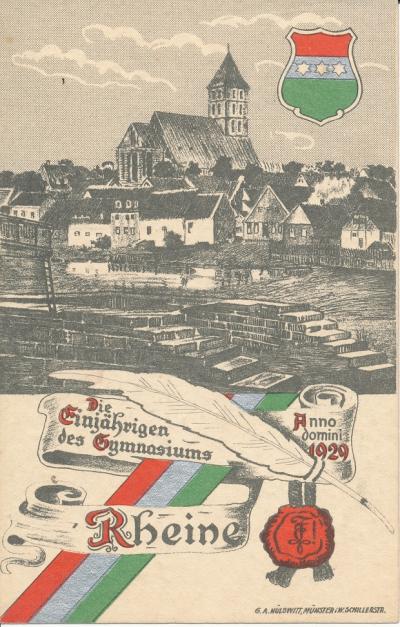

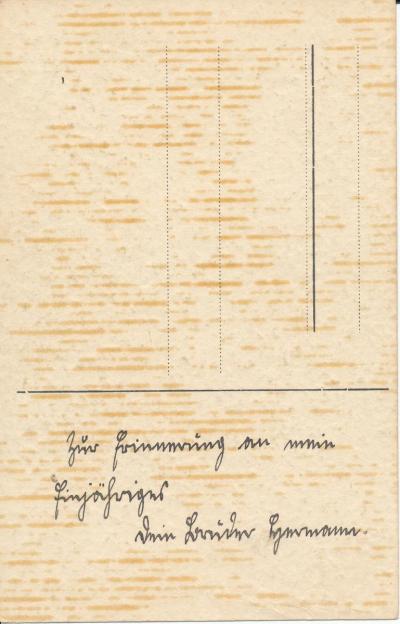

Hermann Scheipers was born on 24th July 1913 in Ochtrup. In 1928 he passed his A-level examinations in Rheine, and one year later he liberated himself symbolically from his previous life when, during the first anniversary celebrations of his leaving school, he threw his old school books into the Ems and decided to become a priest. Nonetheless he has remained open to the world and interested in foreign countries and languages. During his lifetime he has travelled through France by bike, and even managed with the help of a trick to get himself a trip on a cruise to Norway promoted by the Nazi organisation “Strength through Joy”.

On 1st August 1937 he was ordained as a priest in St. Peters Cathedral in Bautzen and took up the post of chaplain in Hubertusburg near Leipzig. Even then he began making contacts with the many Poles living there. In his book “Balancing Act” (1939) he describes a remarkable episode: “In 1939 I drove a Polish woman to Leipzig because she wanted to visit the Polish Embassy there. It was the day after the so-called “Night of Broken Glass”. We drove through the shards of broken shop windows, a number of Jews were standing in the water from the River Pleiße, and the embassy courtyard was packed with Polish Jews in search of protection”.

After the German invasion of Poland, which triggered off the Second World War on 1st September 1939, the priest was confronted for the first time with the injustices inflicted on Poland by the Germans, when Polish citizens were deported to Germany as slave labourers. Without further ado Hermann Scheipers organised pastoral care for them, since it was not expressly forbidden to hold supplementary church services for Polish forced labourers. With the help of an interpreter from the forced labour camp in Mahlis, who translated the gospel into Polish, he prepared a Sunday service for the Poles.

The Mayor of Wermsdorf promptly reported it to the Gestapo in Leipzig. In 1940 Scheipers was summoned there for interrogation. Here he was arrested on the grounds of his refusal to refute his faith and calling as a priest and to disassociate himself from providing pastoral care to Polish forced labourers. On 24th December 1940 at 4 o’clock in the afternoon he was taken into “protective custody”, an act of supreme cynicism. Thus began a life of martyrdom in Nazi Germany. On 20th March 1941 he was taken to the concentration camp in Dachau. Here more than 1000 priests and other clergy were permanently thrown together in Block 26, where they were subject to a daily programme of humiliation and torment.

All in all, 2,720 priests were imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp, of whom 1,034 of them died there. The situation of Polish priests was particularly difficult in the camp; Scheipers remembers that they were subject to especially cruel treatment at the hands of Communist-orientated Kapos. When they were isolated and banned from taking part in daily church services Scheipers smuggled wine and altar bread for them.

Later the Oscar-winner Volker Schlöndorff was to consult Hermann Scheipers whilst he was shooting his film “The Ninth Day” (2004), a film dealing with the fate of the clergy in Dachau, based on the autobiographical novel by Father Jean Bernard entitled “Priestblock 25487”.

Hermann Scheipers was saved from the gas chamber by his twin sister on 13th August 1942. After a secret meeting with her brother in Dachau she made a private visit to the civil servants in the Central Reich Security Office in Berlin who were responsible for the imprisoned priests. Following a dramatic conversation she received a promise from the civil servants that her brother would not be gassed. This promise also applied to all the other priests. Indeed, from that moment on, no priests were sent to the gas chamber. Thus Anna Scheipers not only saved her brother’s life but those of more than 500 other priests.

In Dachau Scheipers constantly witnessed the cruel treatment and deadly human experiments on the prisoners. Many of them were immersed in cold water to test the limits of hypothermia. The experiments were needed in order to develop special clothing for the Armed Forces. According to Scheipers: “All of them died when their body temperature sank to 27°. Only one Russian held out to 17°”. Nonetheless Scheipers’ faith and reinforced inner conviction prevented his feelings from being deadened. Indeed the opposite was true. He remained constantly full of hope and gave aid to his co-prisoners, in particular the Polish priests, wherever he could. He also began to take an interest in the Russian language.

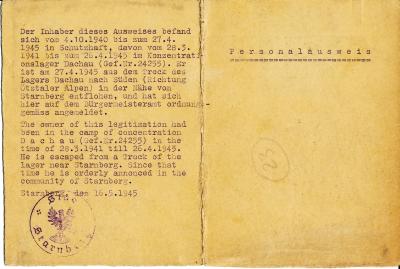

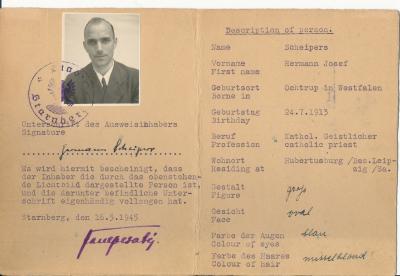

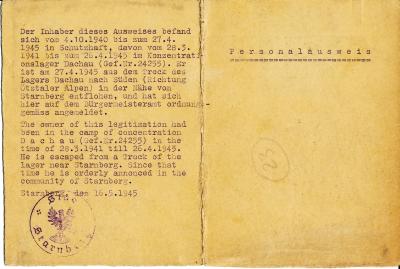

As the Allies approached, the Dachau concentration camp was evacuated in April 1945 and death marches began for the prisoners. On 27th April 1945 Scheipers fled from the death march and hid in a priest’s house in Starnberg. At the end of the war the American occupying authorities in the town of Starnberg issued him with an identity card as early as 16th May 1945. He still regards this card as a “relic”.

After his return to Ochtrup he remained there for a year before taking over the post of chaplain for the bishopric of Meißen in Radebeul, and later in Pirna, Wilsdruff and Schirigswalde Scheipers then found himself in the midst of a second German dictatorship in the form of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Despite harassment he refused to leave his posts, and was even responsible for building the first church in the GDR, the parish church in Wilsdruff.

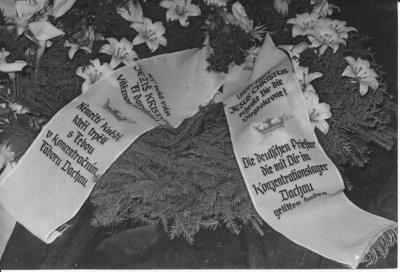

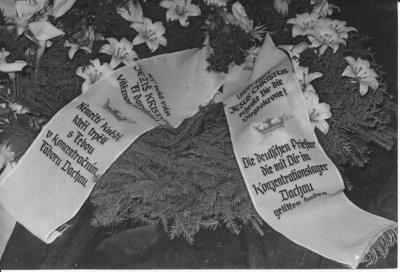

In 1974 Cardinal Stephan Trochta, who befriended Scheipers whilst they were both interned in Dachau, died in Czechoslovakia. Trochta, who had also suffered under two dictatorships (including seven years in prison in Czechoslovakia, was made Bishop of Litoměříce / Leitmeritz in 1948. His funeral was transformed into a political demonstration when it was attended by over 3000 mourners, including cardinals and bishops from all over Eastern Europe. The State Security Service had forbidden anyone from delivering a funeral oration. Despite this Scheipers gave a spontaneous speech in German in which he said: “Dear brother and comrade in the Dachau concentration camp! From the days of your youth you served our Lord Jesus Christ and followed him with courage and faith on his way to the cross. You fought tirelessly for the freedom to believe and for the church without fearing your enemies’ threats. And for this you were forced to endure imprisonment and heavy tribulations. May the Lord now give you his peace and the crown of eternal life.” In addition Scheipers organised a wreath in the name of the prisoners in Dachau. The ribbon contained the following inscription in German and Czech: “May our Lord Jesus Christ give you the crown of victory. The German priests who suffered with you in the Dachau concentration camp”. The wreath was placed in a prominent position right at the front of the casket. Another silent witness at the funeral ceremony was the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, who was to become Pope Paul II four years later, and with whose support the communist system in Eastern Europe began to collapse for good.

Hermann Scheipers returned to the Federal Republic of Germany in August 1983 after his retirement, and came back to live in Ochtrup in 1990. Here he and his twin sister Anna were presented with the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany on 25th November 2002. On 26th February 2013 Hermann Scheipers was awarded the Knights Cross of the Order of Merit from the Republic of Poland. Hermann Scheipers is an honorary citizen of the towns of Ochtrup, Wilsdruff and Williamsport (USA).

Hermann Scheipers died on 2nd June 2016 in Ochtrup.

After the CDU Council faction had taken an initiative to ensure that Hermann Scheipers was appointed honorary citizen in Ochtrup, it applied in August 2016 after his death as a further contribution to the history policy and culture of remembrance a "Stolperstein" (stumbling block) for Hermann Scheipers to relocate - an international project of the Cologne artist Gunter Demnig, which keeps the memory alive of all persecuted in National Socialism. On the 3rd February 2018 the stumbling block with the life data of Hermann Scheipers was put on a square brass plate in front of the former parental apartment in the pavement of the sidewalk by the artist, who had traveled to Ochtrup from Cologne. A commemorative plaque reminds at eye level of the special moral courage of the twins Anne and Hermann Scheipers.

Jacek Barski, June 2015

The list of martyred priests compiled by Hermann Scheipers on the basis of his personal memories and research.

On the grounds of their pastoral and humanitarian help to forced labourers the following persons suffered a martyr’s death:

Adametzki, Josef (Breslau), died 1944 in Auschwitz

Aeltermann, Johnnes (Danzig), shot 1939 in Danzig

Bioly, Peter (Leitmeritz), gassed 1942 in Hartheim-Dachau

Boehm, Franz (Köln), died 1945 in Dachau

Drosdek, Paul (Breslau), died 1945 in prison in Magdeburg

Drosniak, Peter (Hiltrup – Missionary), died 1945 in Russia

Fränznick, Anton (Freiburg), died 1944 in Dachau

Froehlich, August (Berlin), died 1942 in Dachau

Görsmann, Gustav (Osnabrück), died 1942 in Dachau

Guzy, Johann (Breslau), shot 1945 in Freystadt

Karbaum, Ernst ( Danzig), died 1940 in the Stutthof concentration camp

Koplin, Anizet (O.M.Cap.), murdered 1941 in Auschwitz

Korczok, Anton (Breslau), died 1941 in Dachau

Kremer, Joh.-Leodegar (Pallottine Brother), executed 1944 in Brandenburg-Görden

Lenzel, Josef (Berlin), died 1942 in Dachau

Markötter, Elpidius (Franciscan friar), died 1942 in Dachau

Moritz, Aloys (Ermland), died 1945 in Russia

Olszewski, Leo (Ermland), died 1942 in Dachau

Poether, Bernhard (Münster), died 1942 in Dachau

Richarz, Everhard (Köln), murdered 1941 in Mondorf

Schubert, Augustinus (Augustinus hermit), died 1942 in Dachau

Schwarz, Paul (Ermland), murdered 1945 in Frauwalde

Spix, Alphons (Kloster Arnstein), died 1942 in Dachau

Wessing, August (Münster), died 1945 in Dachau

Witt, Gerhard (Ermland), murdered 1945 in Elbing

Witt, Max (Schneidemühl), died 1942 in Dachau

Willimsky, Albert (Berlin), died 1940 in Sachsenhausen

Zurawski, Alfons (Leutenant), executed 1942 in Brandenburg-Görden

Zuske, Stanislaus (Ermland), gassed 1942 in Hartheim-Dachau

Apart from these twenty-nine persons who gave their lives for forced labourers The documentation “Priests under Hitler’s Terror” contains a further 658 names of priests who suffered persecution at the hands of the National Socialists on the grounds of their commitment to forced labourers. Punishments ranged from warnings, via deportation, fines and imprisonment all the way to imprisonment in a concentration camp.

Further reading:

Hermann Scheipers, Gratwanderungen, Priester unter zwei Diktaturen, St. Benno-verlag, Leipzig 2013

Halmut Moll (ed.), Zeugen für Christus, Das deutsche Martyrologium de 20. Jahrhunderts, Paderborn, München, Wien, Zürich, 1999

Media

Dir gehört mein Leben. Die Geschichte von Anna und Hermann Scheipers. Zivilcourage und Gottesvertrauen unter zwei Diktaturen. A film (ca. 30 minutes.) and an interview with Hermann Scheipers in four sequences (ca. 28 min.) produced by the LWL-Media Centre for Westphalia in Münster, 2011

Hermann Scheipers, conversation with Jacek Barski on 12th May 2015 in Ochtrup, in collaboration with the LWL-Media Centre for Westphalia, Münster

Thanks

We should like to thank Benno Hörst from Ochtrup, an elected member of the LWL assembly for putting Prelate Scheipers in contact with the LWL Media Centre and Porta Polonica.