The “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”) 1938

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Alina Bothe - Kuratorin der Ausstellung "Ausgewiesen!" in Berlin

“We were only allowed to take the most basic essentials with us, and were brought to the station under constant guard. It is almost impossible to describe this feeling, but this moment still haunts me to this day. That day, we lost everything we had, our old life, our home and our family.”[1] This is how Siegfried Jaffe, who was 15 at that time, remembers the “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”). His parents, Erna and Lazar, had come to Germany from Galicia after the First World War. The fate of this young boy, who had been born in Berlin, was shared by thousands of Polish Jews at the end of October 1938.

The Jews had been the target of harassment long before the “Polenaktion”, however. Since Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, their situation in the German Reich had systematically deteriorated. Anti-Semitism was not a new phenomenon either in Germany or elsewhere in Europe, but under the National Socialists, it became a state doctrine.[2] Repressive measures, incitement to hatred and the growing level of propaganda against Jews, as well as the boycotting of their participation in public life, had become an everyday occurrence. In total, around two thousand anti-Semitic laws and regulations that discriminated against people of the Jewish faith were passed and introduced in the “Third Reich”.[3]

The Jews living in Germany who originally came from eastern Europe, known derogatively as the “Ostjuden”, were in the particularly precarious position of being right at the bottom of the hierarchy of “unwanted” (i.e. Jewish – translator’s note) citizens. According to the census of June 1933, the population of the “Third Reich”, which at that time totalled 65 million, included around half a million Jews, of whom 100,000 did not have German citizenship. By far the largest proportion of this group (60,000) were Polish citizens, while a further 20,000 were of Polish origin.[4] Most Jews of Polish origin had come to Germany during the chaos of the First World War from 1914–1918. Some had arrived as prisoners, while others were forced labourers or economic migrants. For others, Germany was originally intended only as an intermediate stop en route to the United States. However, in the end, they had remained there since for various reasons they were unable to make the journey across the ocean.[5]

The unceasing acts of violence, the restriction of their citizens’ rights and the introduction of employment bans against the Jews meant that their living conditions as a group within society deteriorated continuously and they lived their lives in constant fear. As a result, they emigrated to different countries in increasing numbers. By 1938, around 250,000 Jews had left the German Reich.

For the National Socialists, who had already publicly stated at an NSDAP meeting in 1920 that they intended to “liberate” Germany from all its Jewish citizens, the campaigns against them were progressing far too slowly. When 200,000 more Jews became citizens of Germany following the annexation of Austria on 12 March 1938, the Polish government suddenly and unexpectedly played a part in triggering the events that followed, namely the “Polenaktion”. On 31 March 1938, fearing a wave of impoverished Jewish immigrants seeking refuge in Poland from the anti-Semitic environment under the National Socialists, the Polish Sejm passed a law on the withdrawal of citizenship (Ustawa o pozbawieniu obywatelstwa)[6]. The law stated that any Polish citizen living abroad would have their Polish citizenship revoked “if they have lived abroad for longer than five years following the founding of the Polish state”, or “have lost their connection to the Polish state”[7]. Furthermore, it was decided that the revocation of citizenship of a husband should also extend to that of his wife, and of a father to his children aged 18 or younger “if these persons are living abroad, and if they have not been excluded from the revocation of citizenship in the official revocation decision.”[8]

The German government issued an immediate protest against the new law via diplomatic channels. However, the new regulations were only reluctantly introduced. It was only six months later, on 9 October 1938, that the decision by the Polish government to order mandatory consular stamps in the passports of Poles living abroad was put into action. The consuls were also ordered to retain the passports of those whose citizenship was to be revoked. Passports that did not have a consular stamp automatically expired on 30 October.[9] At that time, the Germans were afraid that soon, there would no longer be anywhere they could send the Jews, particularly since other countries had already closed their borders to them.

A response to the measures taken by Poland came on 26 October, when Heinrich Himmler, head of the German police and Reichsführer-SS, issued the order that all Jews of Polish origin should be expelled from the “Third Reich”. The operation was very carefully planned, and involved a coordinated effort between the SS, the Gestapo, the Deutsche Reichsbahn railway company and diplomatic staff. The responsibility for coordinating the “Polenaktion” lay with the interior ministries of the constituent states (“Länder”). Propaganda in support of the campaign was published by the German press, which also reported, among other things, that the Polish state had “demanded” that the Jews return to their homeland. One example is the article published in the “Rheinisch-Westfälische Zeitung” newspaper in Essen: “A large proportion of the Jews came to Germany after 1918; many Jews from Poland and East Galicia also came to Essen. Since these Jews remained Polish citizens, the Polish state ultimately had no other option than to demand that they now return, and in the event of their refusal, to immediately withdraw their Polish citizenship.”[10]

Himmler’s order was immediately put into practice. The first arrests were already made on 27 October, particularly in the west of the country. However, most of the measures were carried out on 28 and 29 October. The arrests followed the same protocol nearly everywhere. In most cases, officials entered the homes of the people in question in the early hours of the morning, issuing a demand to the astonished residents that they must leave the territory of the German Reich within 24 hours. “We were not, however, granted this period of time and had to follow the officers as soon as we had dressed and were given next to no time to take along clothing and linens. I was forced to leave Germany meagrely clothed and with just a few Reichsmarks.”[11] This is how the Berlin violinist Mendel Max Karp described what happened in a letter to his brother, which he wrote shortly after arriving in the transit camp in Zbąszyń (Bentschen). His detailed report is one of the earliest contemporary witness documents of that time. The majority of the deportees, if they survived the Holocaust at all, only spoke about the dramatic events that occurred decades later.

In Berlin, it was mainly men aged over 15 who were expelled, while in other parts of Germany, entire Jewish families were deported, including children, the elderly and ill family members. Max Karp wrote: “After the people had been gathered in Berlin, we were brought to a freight depot in Treptow in half-enclosed or partially covered trucks under the supervision of the police barracks. In front of the barracks and in the neighbouring streets, emotional scenes took place among the women, mothers, and children left behind in Berlin.”[12]

The report by Ottilie Schoenewald from Bochum, the wife of the chairman of the Jewish community and a member of the board of the Jewish women’s league, was no less disturbing: “The line of cars drove to all the Jewish butchers, bought all the kosher sausages they had, then on to the bakers, who promised to set aside several hundred fresh rolls the following morning. (...) The person on watch, whom I knew, told me that we should eat our food at the station, (...) At the station, a seething mass of flustered, crying, screaming women and children had already gathered, and new cars kept arriving and literally ‘shook’ their miserable occupants out onto the square. (...) When at around 10:30 in the morning we heard ‘everyone onto the platform’ we were overcome by real mass hysteria. Everyone started pushing and shoving, even though in reality, no-one had wanted this moment to arrive. Mothers screamed at their children who were holding their hands or holding onto their skirt hems. The children were crying for their mothers. Every so often, there were people who requisitioned items left behind by someone else.”[13]

The recollections recorded by Ottilie Rimpel from Stuttgart, which have been passed on by her son, are just as disturbing: “We were a group of people in a desolate state – without any idea of what was happening, without luggage – with nothing but the clothes on our backs. We were just the kind of people that Hitler once spoke of in his speech in the market square in Stuttgart. He said: ‘We will throw all the dirty Polish bloodsuckers together with their lice out of here, without clothes and without a penny in their pockets.’ I regret the fact that we didn’t listen to what he was saying at that time, and that we hadn’t read his book ‘Mein Kampf’ and taken it to heart. This odious man was fully aware of everything that he wrote and said. The people called it propaganda. However, it was the bitter truth, as we would later find out.”[14]

The “Polenaktion” was the first mass deportation of the Jews from the “Third Reich”. It was carried out entirely in the open, and the German population would have been fully aware of it. By that time, anti-Semitic sentiment was so widespread in society that the arrests were met with silent agreement and sometimes even open enthusiasm. As Mendel Max Karp recalled: “One truck after the other left the barracks courtyard with us in them, a long chain of monstrous vehicles snaked across the “Alex” [Alexanderplatz – author’s note] and through the city, accompanied by the deafening din of sirens, sounded intentionally to alert the population of Berlin to our forced deportation. The people amassed in the streets, witnesses to the ‘historic’ expulsion of the Jews from Germany.”[15]

In effect, the “Polenaktion” was a logistical dress rehearsal for the National Socialists in order to determine how smoothly the state organs were able to carry out the deportations. And even though the campaign involved an enormous amount of effort, not everything went according to plan. This was the case in Leipzig, which at that time was home to over three thousand Jews of Polish origin. They accounted for a third of the Jewish population in the city. The Consul General of Poland in Leipzig, Feliks Chiczewski (1889–1972), had long been aware of the increasingly difficult situation for the Jews in Germany. Just two days before the “Polenaktion”, Chiczewski sent a report to the Polish Ambassador in Berlin, Józef Lipski, in which he described the intensification of the measures against members of the Jewish faith as a “war that has been declared against the Jews by the National Socialist party and which will inevitably end with their complete destruction”[16].

When news of the first arrests in other cities in the Reich reached Leipzig, the diplomat attempted to negotiate an agreement with the police and the local authorities whereby women, children and the sick were to be excluded from deportation. The Chief of Police initially agreed to the proposal, although on condition that the Jews to be deported were able to provide proof that they wanted to leave Germany anyway. However, when the negotiations stalled, Chiczewski informed all the Polish Jews that they must present themselves at the consulate. Those who had a telephone informed their families, friends and acquaintances, and within just a short space of time, around 1,300 people arrived at the villa where the consulate was housed in Wächterstrasse 32.[17] A report from that time states the following: “The entire large garden, all the entrances, the stairs, the waiting room, the cellar rooms and a portion of the private chambers of the Consul and the laundry buildings were full of refugees.”[18]

By taking the Jews into the consulate premises, Chiczewski guaranteed them extra-territorial protection. He also issued them with passports, regardless of their residential status. The Gestapo, which was based in the same street, did not dare to intervene on the entire consulate site, since it was regarded as inviolable. The Jews saved by Chichzewski on 29 October then left the villa in Wächterstrasse and returned to their homes. Many of them did indeed leave Germany shortly afterwards. Those who were unable to seek refuge in the consulate were arrested by the police and taken to the main railway station. From there, they were transported in four trains to Beuthen (now Bytom), where they were chased across the border.

In the space of just two days, over 17,000 Jews were expelled from the “Third Reich”. The numbers deported from individual towns and cities are based only on estimates: 1,500 from Berlin, 1,000 from Hamburg, including women and children, 600 from Dortmund and Cologne, 420 from Essen, 361 from Düsseldorf and 70 from Gelsenkirchen.[19] In spite of all this, until recently, only a small number of people were aware of the existence of the “Polenaktion”, even though there were some individuals who became highly successful in later life among the deported.

They included Gerhard Klein (1920–1999), who was 18 at the time, and who was a young star in film and on stage. He became famous in the role of the professor in “Emil und die Detektive”, a play based on the novel of the same name by Erich Kästner which was popular at the time. Klein performed at the Berliner Theater, the Jüdisches Theater (Jewish Theatre) and the Kindertheater des Kulturbundes (League of Culture Children’s Theatre), among others. He also played a lead role in the 1931 film “Dann schon lieber Lebertran” (In that Case, I’d Prefer Cod-Liver Oil) by Max Ophüls, before his career came to a halt when the National Socialists came to power and prohibited actors of Jewish origin from working. Like his brother, Gerhard Klein was born in Berlin. Both siblings had nothing to do with Poland and did not even speak Polish. It was because of their father, who was born near Oświęcim (Auschwitz) that they had Polish citizenship. Nevertheless, they were forced to leave Germany and move to an unknown country.

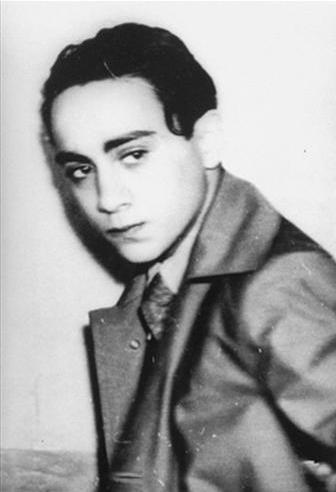

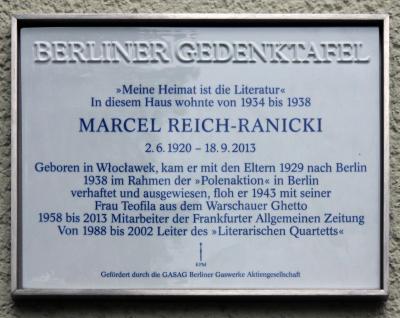

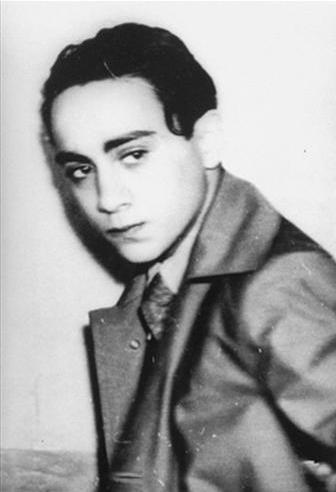

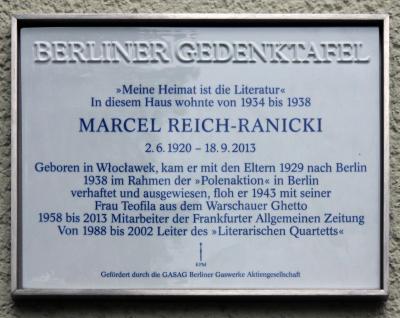

One common characteristic for many deportees with Polish citizenship was that they felt themselves to be German. This was also true of Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who had to leave Germany at 18 during the “Polenaktion”. Reich-Ranicki, who later became known as the “Pope of Literature”, was born in Włocławek in 1920. Of himself, he said that he was “half-Pole, half-German and whole-Jew”. He had left Poland aged nine, when his family, who suffered from financial difficulties, moved to Berlin. As was the case with all Jews, Ranicki’s rights were severely curtailed following the seizure of power by the Nazis. While in 1938, he was still permitted to take his “Abitur” school-leaving exam, his application to enrol as a student at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin (renamed Humboldt-Universität after the war) was rejected due to his Jewish origins.

Several months later, on 28 October, shortly before seven in the morning, the police knocked on the door of the tiny room where the family lived at 16 Spichernstrasse, in the Berlin district of Wilmersdorf. The 18-year-old Ranicki was handed a document ordering him to leave Germany within 14 days. However, the order was carried out immediately. “Needless to say, I had to leave everything behind that I had in my little room. I was only allowed to take five marks with me, as well as a briefcase. But I did not quite know what to put in it. In the hurry, I put in a spare handkerchief and something to read.”[20]

At first, Ranicki suspected that someone had denounced him; he was unaware of any reason for being arrested, and the situation felt utterly unreal. He later discovered that the only “reason” was his Polish origins. In his autobiography, “The Author of Himself. The Life of Marcel Reich-Ranicki”, which was published decades later, the famous literary critic describes the others who were deported as follows: “They were Jews and all older than me, the eighteen-year-old. They were speaking perfect German and not a word of Polish. They had either been born in Germany, or had come to Germany as small children and attended school there. But like me, they all, as I soon discovered, had Polish passports.”[21]

We have Marcel Reich-Ranicki’s memoirs to thank for one of the most detailed descriptions of the expulsion of the Jews: “We were not told where the train was going, but it was soon clear that it was going east – to the Polish frontier. We were freezing, the carriages were not heated, but everyone had a seat. Compared to subsequent transports, these were humane, almost luxurious, conditions. (...) At the German frontier, we had to get off the train and form up in columns. There were shouted commands, many shots, shrill screams in the darkness. Then a train arrived. It was a short Polish train, into which the German police now brutally drove us. The carriages were crammed full. The doors were immediately slammed shut and sealed, and the train pulled out.”[22]

The trains carrying the deportees from Germany arrived in Beuthen (Bytom), Konitz (Chojnice) and Kreuz (Krzyż). For most of the Jews, the journey continued on to the final stop in Zbąszyń, the small town which after the re-establishment of the Polish state found itself directly on the border with Germany. The first trains were able to travel across the border, since the Poles were entirely taken unawares: the imminent wave of expulsions was not reported to the border guards, nor to the local authorities in the towns and villages close to the border. However, as an ever-increasing number of trains continued to arrive, the Polish authorities first refused to allow them into Poland, and they were forced to stop several kilometres before the border, in no-man’s land. From there, the Jews were chased through forests and swamps towards Poland, accompanied by threats and under fire by the Nazis. “We had no knowledge either of where this path was taking us, or of what fate held in store for us. Hours later, we spotted a white-and-red striped barrier that crossed the path, and as we came closer, a Polish flag. Near the border, there were swamps and muddy wetlands on both sides of the path. This was the ‘no-man’s land’ between Germany and Poland. Suddenly, the Germans began shooting at the long column of Jews – men, women and children. We fled into the wetlands. My father pulled me down and pushed my head deep into the mud. At that moment, I thought that my beloved father was trying to drown me! Finally, the shooting stopped. Covered in mud, we slowly crept out of the swamps, waded through the river and reached Polish territory. Six Polish border officials – and no more – faced the armed German soldiers.”[23] This is how Willi Najman, who was nine years old at the time, and whom the German police collected from his school in Hamburg before deporting him and his family, remembered his journey to Zbąszyń.

It is not known how many Jews paid with their lives for these transports and the flight into Poland via no-man’s land. By the time the government in Warsaw had finally permitted the deportees to enter Poland, many of them had already made it across the border. Within just two days, between 8,000 and 9,500 people, over half of whom were Jews of Polish origin who had been expelled from Germany, arrived in Zbąszyń, a town with a population of just over 4,000. From one day to the next, Zbąszyń became a vast refugee camp. It was simply impossible to provide shelter for such a large number of people. Some of them were housed in the station building, in the mill or in the former barracks, while others were forced to camp out in the open air. In time, people began taking Jews into their private homes.

In the interim, Poland began negotiations with Germany, requesting permission to return the deported Jews to the “Third Reich” and compensation for the possessions that they had lost, or for the transfer of these goods to Poland. Finally, in January 1939, it was agreed that the relatives of the deportees who were still living in Germany would be allowed to join them in Poland. Those who had been forced to leave their property behind were permitted to return to Germany for one month in order to put their affairs in order. To be able to do so, they were required to pay the capital obtained from the sale of their goods into frozen bank accounts in Germany.[24] After the Second World War broke out, they were no longer able to access their assets.

Anyone who was able, or rather, those who had sufficient funds, left Zbąszyń as quickly as possible and travelled further inland into Poland or emigrated to other countries. During the first few days, around two thousand people left the town, including Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who travelled to Warsaw with his family. The Poles and the employees of the Jewish charity organisations who were sent to Zbąszyń to help did all they could to provide halfway decent living conditions for those who remained behind. Blankets were collected and hot food and drinks were handed out. When the supply of bread ran out on the first day, the mayor of Zbąszyń set a fixed price for bread in order to prevent speculation and the inevitable price rises that would result for this valuable commodity.

Despite the lack of warmth felt towards the Jewish community in Poland at the time, the local population rushed to help the deportees: As Wojciech Olejniczak, chairman of the “TRES Foundation” (Fundacja TRES), whose work includes preserving the memory of what happened in Zbąszyń, recalls: “The sudden arrival of such a large number of hungry, freezing, clearly frightened people triggered a natural human desire to help among the locals.”[25] Many of the deportees who reported on the events many years later expressed their gratitude towards the local population for their humane solidarity. These accounts are stored in the archives by the American USC Shoah Foundation and the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem and elsewhere. In the words of the historian Jerzy Tomaszewski, who has also studied the events that occurred: “At that time, the people of Zbąszyń restored the honour of Poland.”[26]

The assistance for the Jews who were stranded in the small town in Greater Poland was funded mainly by Jewish charity organisations. Collections were also organised, in which the people of Zbąszyń were actively involved. Alongside the timely provision of accommodation before the outbreak of winter, the most difficult task was ensuring that the refugees were fed. While field kitchens had been installed in the barracks, people still had to wait in long queues before they were given a meal, and not all of them had warm clothes to wear.[27]

They also suffered from mental stress. The dramatic events, the separation from their families, the loss of their home and possessions and in many cases, their lack of knowledge of the Polish language, led to feelings of anxiety and loneliness. It was under these circumstances that small shops began to open in Zbąszyń that catered to everyday needs. Soon, hairdressers, tailors and cobblers appeared, followed by various manual trades, a separate post office and a sanitation service. The aim was to integrate as many of the deportees as possible into “normal” life and in so doing, prevent them from sinking into inactivity and apathy. Isaac Giterman, the Polish director of Joint Distribution Committee, an international aid organisation which provided assistance to the deported Jews on site, described the situation as follows: “At least everyone now has a pallet on which to sleep. The children and sick people get milk each day, there is enough linen to go round and some people have been given clothing. After beginning in total despair, there are now discussion evenings for Zionist youth groups and lessons in Polish. … The most moving plea came from the children, who asked if all under-16s could meet in a room so that they could play.”[28]

Very soon afterwards, the Polish authorities sealed off the town and refused to allow the deportees to leave. Lists were passed around inside the camp to which people who wished to emigrate to Palestine, the US or other European countries could add their names. However, for many, this was not a possibility. Some of the children were saved by the “Kindertransporte”, trains organised and operated by the British government in the wake of the “Night of Broken Glass” (“Kristallnacht”), which enabled children and teenagers aged between four months and 17 years to be rescued. Overall, around 10,000 children from Poland, Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia were brought to safety in Britain in this way. The young refugees were taken in by host families or in children’s homes. Many of them would never see their parents again after saying goodbye. Most of the Jews deported during the “Polenaktion” campaign were later murdered in the Holocaust.

Those who were left stranded in Zbąszyń included the parents and siblings of Herschel (Hermann) Grynszpan. They were taken from Hamburg as Polish citizens, even though they had lived in Germany for 27 years. On 3 November 1938, the 17-year-old, who was hiding from the police and who was at that time living illegally in Paris, received a postcard from his sister Berta telling him about his family’s deportation from Germany and asking for financial help. The next day, Herschel read a detailed report about the hopeless situation of the deportees in Poland in a French newspaper, and decided to commit an act of revenge in protest against the anti-Semitic policies of the Nazis. On 7 November, Grynszpan purchased a revolver and that same morning, appeared at the German Embassy in Paris. Claiming that he needed to submit some important documents, he was received by the Embassy secretary, Ernst von Rath. When he entered von Rath’s office, Grynszpan fired five shots at the diplomat, two of which caused severe abdominal injuries. Grynszpan was immediately arrested while still in the building. Despite being treated by Hitler’s personal physician, von Rath died two days later. The National Socialists used the incident as a pretext for the “Kristallnacht”, which took place across Germany on the night of 9 to 10 November. Approximately 400 Jews died during these pogroms. Several hundred more were murdered in the days that followed. During the course of that night, the Nazis destroyed or set fire to 1,400 synagogues and prayer rooms, as well as thousands of Jewish shops, apartments and gravesites. On 10 November, 30,000 Jews were arrested and taken to concentration camps.

Ultimately, the dramatic events of the “Kristallnacht” meant that the world almost forgot about the “Polenaktion” entirely. Although the first coordinated mass deportation of the Jews shocked people throughout the world, and news of the events dominated the front pages of most of the European daily newspapers, the situation quickly changed less than two weeks later. The scale of the November pogroms overshadowed everything that had happened previously. For many years now, the Fundacja TRES has been working in Poland to remind people of the “Polenaktion” and the unprecedented help offered by the Poles for the Jews who were driven from Germany. To mark the 80th anniversary of the “Polenaktion”, the descendants of the deportees visited Zbąszyń for the first time.

Monika Stefanek, February 2019

Online information about the “Polenaktion”: https://zbaszyn1938.pl/?s=szukaj&lang=EN