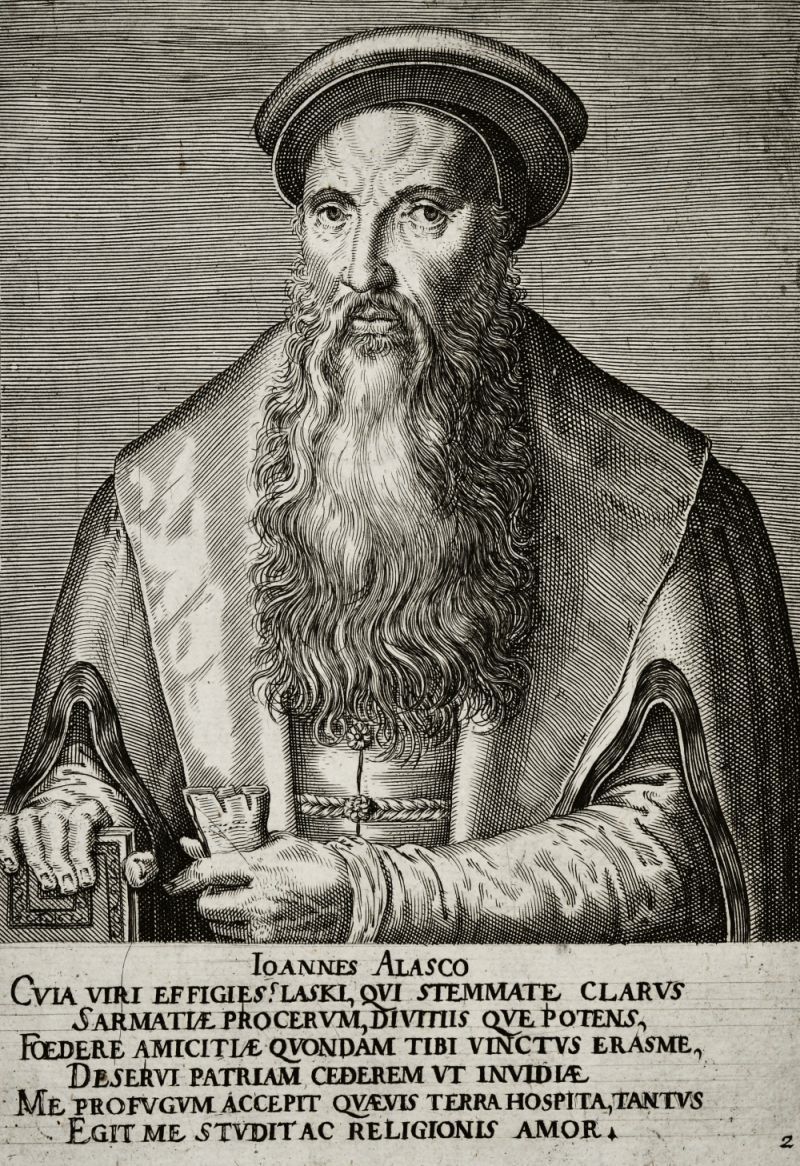

Johannes a Lasco

Mediathek Sorted

![Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal Fig. 4: Response to Joachim Westphal - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Responsio ad uirule[n]tam, calumniisque Ac Mendaciis Consarcinatam hominis furiosi Ioachimi VVestphali Epistola[m] quandam, qua purgationem Ecclesiaru[m] Peregrinarum Francofor...](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/4_antwort_auf_joachim_westphal_1560.jpg?itok=Pd3diTmf)

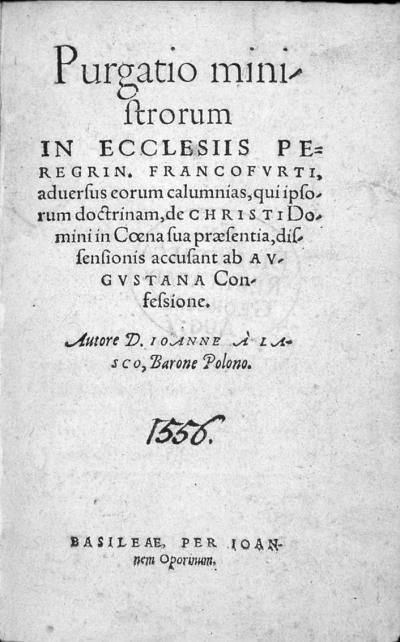

![Fig. 5: Three letters Fig. 5: Three letters - John à Lasco/Jan Łaski: Epistolae tres lectu dignissimae, de recta et legitima ecclesiarum benè instituendarum ratione ac modo: ad Potentiss. Regem Poloniae, Senatum, reliquos[que] Ordines, Basel 1556](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/5_drei_briefe_1556.jpg?itok=hQ0svO_N)

John à Lasco – A Polish Reformer in East Frisia

It is thought that Jan Łaski, the Latin form of which, Johannes à Lasco, is passed down from documents and writings of his day and which in recent times has become established in Germany,[1] was born in 1499 in what today is the district town of Łask, twenty kilometres to the south west of Łódź, into a family of prosperous and politically influential Polish nobility. The family owned three larger towns, Łask, Stryków and Bolesławiec, and around forty villages in various areas of Greater Poland and Lesser Poland. His father Jarosław was made Vovoide of Sieradz in 1511. His mother, Zuzanna z Bąkowej Góry, brought an extensive estate into the marriage. His eldest uncle on his father’s side, Andrzej, was a priest in Sieradz, Krakow, Poznań and Gnesen and died in 1512. His youngest uncle, Jan Łaski (the Elder, 1456-1531), was made Royal Secretary in 1501, Grand Chancellor in 1503 and Archbishop of Gnesen in 1510 and thus Primate of the church in Poland.[2]

Jan Łaski the Elder's prominent position meant that, under the reigns of Kings Aleksander Jagiellończyk (1461-1506) and Sigismund I (1467-1548), he was involved in domestic policy reforms and foreign policy achievements, such as the assertion of the Polish suzerainty over the German order or the marriage of the King to the Italian Princess Bona Sforza (1494-1557), but he was also involved in discussions about Poland’s relationship with the succession in Hungary and with the House of Habsburg. As Archbishop he took part in the fifth Lateran council in Rome in 1512-17, convened Provincial Synods and repressed the first sways of the Reformation in Poland.[3] Within his family, the Primate took care of all his brother Jarosław’s children: He used dowries to facilitate the marriages of his three nieces to noblemen. He brought his nephews Jarosław (*1496), Jan and Stanisław (*1501) to his court in Kraków where he afforded them an extensive humanist education. During the Roman Lateran Council, the Primate sent all three nephews to study at the universities in Rome, Bologne and Padua from 1513.

John stayed in Italy for six years from the age of 14. During this time, his uncle obtained ecclesiastical benefices for him in Poland, which meant that he more than enough income from spiritual offices and titles, some of which were in Gnesen and Kraków. When he returned to Poland in spring 1519, not only was he financially secure, he was also predestined for the highest secular and ecclesiastical offices and privileges. In 1521, he was ordained a priest, elected dean of Gnesen and appointed Royal Secretary.[4]

At a young age, Jarosław, the elder brother, was sent on royal assignments and on diplomatic missions abroad. In 1520/21, he and a Polish delegation attended the coronation of Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) in Bologna and during his trip he met the humanist Augustinian canon and priest Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466/69-1536) twice, once in Cologne and once in Brussels. His writings had been printed in Poland as early as 1518, predominantly in Kraków where they had been well received. In January 1524, Jarosław was sent to the French court in Paris and was accompanied by John and Stanisław. The Łaski brothers travelled via Switzerland, where they met the reformer Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) in Zurich and visited Erasmus at his property in Basel. In 1544, John would later say that it was Erasmus “that made me turn to religious matters, yes, he was the first to start to teach me true religion”.

[1] German encyclopaedias also give other names, such as Johannes Laski (Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, 1883; Neue deutsche Biographie, 1982) or Jan Laski (Theologische Realenzyklopädie, 1990; Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 2002). In common use in the English-speaking world are Jan Laski (Encyclopædia Britannica), John Laski, John à Lasco, Johannes Alasco, and in France Jean de Lasco.

[2] Henning P. Jürgens 2002 (see Bibliography 3.), p. 19-22

[3] Ibid, p. 22-26

[4] Ibid, p. 26-32