Sławomir Elsner. Precision and Chance

Mediathek Sorted

![Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913) Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913)](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/Titelbild_23.jpg?itok=J58T-JmV)

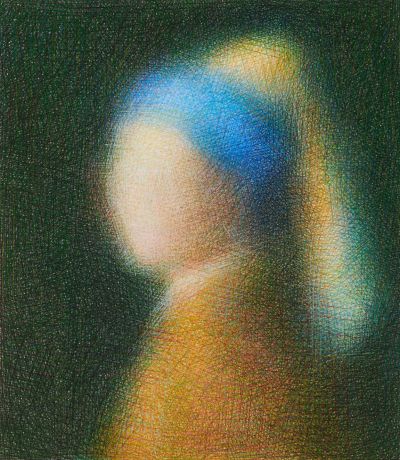

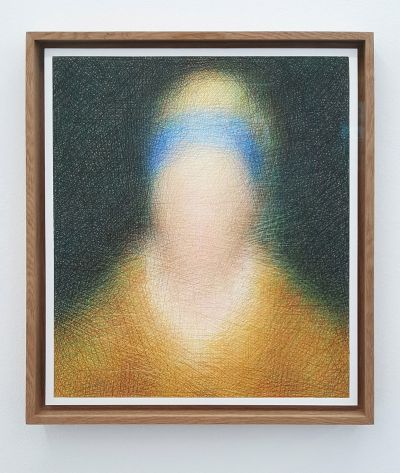

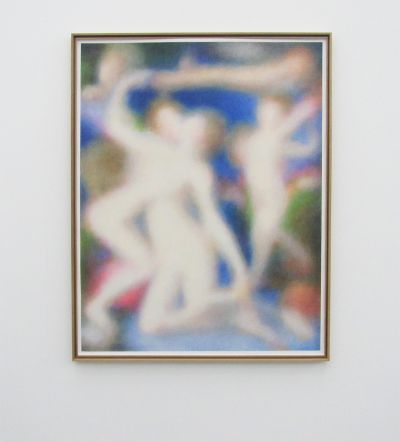

Sławomir Elsner has the ability to look behind visual worlds, image patterns and image practices. In the Museum Wiesbaden, where his latest exhibition is to be held, he can also be found visiting the historical collections in the well established museum, the founding of which stretches back to Goethe’s time and which shows art ranging from Gothic, through Art Nouveau and Expressionism, up to the present day. For Elsner, the image and design patterns of older art history and of the modern age are an open book, as is popular imagery, like photographs and press images, the motifs of which he has scrutinised and processed in various ways in his artworks over the last two decades. On the face of it, you can see that he has borrowed from twentieth century art, for instance from colour field painting, photo realism, pop art and Gerhard Richter, whose leanings Elsner has not only modified but also scrutinised through his sophisticated painting and drawing techniques. Without exact knowledge of his time-consuming work processes, the aesthetics and the content-related interpretation of his different work groups are hard to decode. Even the artist himself has a tendency to withdraw from the forefront of the art business into the meditative stillness of his Berlin atelier and to speak more reservedly about himself and about his work. But he has numerous groups of work, long lists of solo and group exhibitions and catalogues to show for his efforts, and they document the individual phases of his works to date in detail.

A series of twenty small, staged colour photographs date back to his time as a student and show the artist in different professions – as a kebab seller, teacher, farmer, doctor, orchestra musician, or policeman (Fig. 1–8 ) – and pose the question at different levels about his own identity: Are they professions that he can picture himself doing, or ones that he has actually worked in or ones into which he gives us realistic insights in their setting, wearing new costumes each time? Reproduced as a set (Fig. 9 ), the conceptual principle of the artistic activity becomes clear. Whether posted in individual photographs on social media or displayed in Wiesbaden at different positions in the historical collection, we remain unsure of whether the artist is actually showing us himself “Slawomir” (1999), or the role of private photos between snapshot, documentation and self-staging with all their technical deficits that are intrinsic to the image.

For him, even if it was on another level, the photograph remained the fundamental medium for preparing an image as he began to convey his own snapshots as watercolours and later as coloured-pencil drawings. In the series entitled “1 November” (Fig. 10 ), for which five watercolours were produced between 1999 and 2002, the artist concentrated on the light and colour phenomena resulting from the underexposure of the preceding night scenes. He conveys an image of the emotional atmosphere that ensues when family members in Poland visit the cemeteries on the Catholic holiday All Saints’ Day so that they can decorate the graves of their relatives with flowers and light candles. The blaze of lights in the darkness lights up human existence between past, memory and living present.

![Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913) Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913)](/sites/default/files/styles/width_800px/public/Titelbild_23.jpg?itok=31IcSIIx)