Sławomir Elsner. Precision and Chance

Mediathek Sorted

![Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913) Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913)](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/Titelbild_23.jpg?itok=J58T-JmV)

Sławomir Elsner has the ability to look behind visual worlds, image patterns and image practices. In the Museum Wiesbaden, where his latest exhibition is to be held, he can also be found visiting the historical collections in the well established museum, the founding of which stretches back to Goethe’s time and which shows art ranging from Gothic, through Art Nouveau and Expressionism, up to the present day. For Elsner, the image and design patterns of older art history and of the modern age are an open book, as is popular imagery, like photographs and press images, the motifs of which he has scrutinised and processed in various ways in his artworks over the last two decades. On the face of it, you can see that he has borrowed from twentieth century art, for instance from colour field painting, photo realism, pop art and Gerhard Richter, whose leanings Elsner has not only modified but also scrutinised through his sophisticated painting and drawing techniques. Without exact knowledge of his time-consuming work processes, the aesthetics and the content-related interpretation of his different work groups are hard to decode. Even the artist himself has a tendency to withdraw from the forefront of the art business into the meditative stillness of his Berlin atelier and to speak more reservedly about himself and about his work. But he has numerous groups of work, long lists of solo and group exhibitions and catalogues to show for his efforts, and they document the individual phases of his works to date in detail.

A series of twenty small, staged colour photographs date back to his time as a student and show the artist in different professions – as a kebab seller, teacher, farmer, doctor, orchestra musician, or policeman (Fig. 1–8 ) – and pose the question at different levels about his own identity: Are they professions that he can picture himself doing, or ones that he has actually worked in or ones into which he gives us realistic insights in their setting, wearing new costumes each time? Reproduced as a set (Fig. 9 ), the conceptual principle of the artistic activity becomes clear. Whether posted in individual photographs on social media or displayed in Wiesbaden at different positions in the historical collection, we remain unsure of whether the artist is actually showing us himself “Slawomir” (1999), or the role of private photos between snapshot, documentation and self-staging with all their technical deficits that are intrinsic to the image.

For him, even if it was on another level, the photograph remained the fundamental medium for preparing an image as he began to convey his own snapshots as watercolours and later as coloured-pencil drawings. In the series entitled “1 November” (Fig. 10 ), for which five watercolours were produced between 1999 and 2002, the artist concentrated on the light and colour phenomena resulting from the underexposure of the preceding night scenes. He conveys an image of the emotional atmosphere that ensues when family members in Poland visit the cemeteries on the Catholic holiday All Saints’ Day so that they can decorate the graves of their relatives with flowers and light candles. The blaze of lights in the darkness lights up human existence between past, memory and living present.

Light phenomena are at the centre of several series of coloured-pencil drawings that were produced between 2003 and 2010 based on his own or other people’s photographs, individual examples of which can be seen in the exhibition in Wiesbaden. The light spectacles depicted stem from catastrophes like the nineteen-part series “Landschaft” [Landscape] (2003) and the twelve-part sequel created in 2004–2005 “Feuerwerk und Luftabwehr” [Fireworks and Air Defence], which were drawn based on pictures of New Year’s Eve fireworks and war photographs from Kosovo and Iraq. The latter, alternately and in medium-sized format, show the light and colour effects of peaceful pyrotechnics and of acts of war, which can hardly be differentiated from one another. In 2005–2007, Elsner conveyed the light phenoma of atomic explosions from press photos to the medium of coloured-pencil drawing in seventeen pieces under the series title “Unsere Sonnen” [Our Suns]. Similar to the photographs, the areas that are radiated by glistening light remain white, as the work “270 Kilotons” in the exhibition demonstrates. The image of a car burning in a dark night in Warsaw is part of a series produced in 2009 and entitled “Paris, Berlin, Warszawa” (all Fig. 11 ). With succinct titles, which are open to all possible interpretations, Elsner works here with an aesthetic of horror, the motif of which recalls Andy Warhol’s series “Death and Disaster” (1962–1965) and especially its screen prints “Atomic Bomb” and “Car Crash” which appeared in many variations and were also based on press photos.

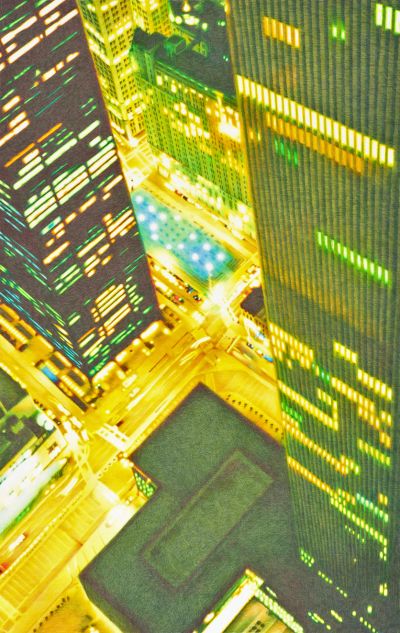

But with his works dealing with the terror attacks on the New York World Trade Center on 11 September 2001, which in our collective memory is the most deeply rooted catastrophe of the past decades, Elsner created a greater distance than just with the title. Instead of the familiar press images of the Twin Towers whilst they burned and ultimately collapsed, in his large-format series in coloured pencil “Windows on the World”, which was produced in 2008 to 2010, he referred back to his own photographs that he had taken a few months before the attack. In the eleven-part series, from which four pieces can be seen in Wiesbaden (Fig. 12–15 ), the originals he used were photos that he had taken himself in 2001 from the windows of the club of the same name Windows on the World on the 107th floor of the building, which looks out over New York in all directions, and in the inside of the restaurant bar. Here, too, the overall impression is conveyed by the light effects and the fuzziness and colour distortions resulting from images taken at night.

Whilst Warhol in the sixties was focusing on popularising image media and the sensation mongering that came with it and on creating new iconic visual worlds from this motif, today the narrative threads and headlines of powerful images are analysed in terms of their relationship to the different levels of the collective memory. In the current excessive world of media and information, image icons are now more likely to be a trigger for memories and emotions which are then joined by more or less interchangeable stories, analyses and sub-texts in print media and on the Internet. Elsner scrutinises and analyses such image icons, press images and private photographs using artistic means by conveying their composition, colourfulness and emotional content in minute detail over many weeks of intense concentration using heavy shading comprising precise lines created by new coloured pencils and in a large format.

This work is performed so meticulously that the newly created works seem like photographs or screen prints from a distance and in reproductions. It is only when seen in the original and up close that the fact that they are composed from an infinite number of differentiated coloured lines is revealed. Through his artistic work, Elsner creates a distance to the subject which provokes questions about its authenticity and emotional effect and which, at the same time, facilitates the transition from one medium to another, i.e. from photograph to a completely new artwork: coloured-pencil drawing. With his protracted, almost meditatively executed drawing technique and the succinct titles of his works, which are combined into series, he achieves the greatest possible distance from subjects that are deeply anchored in the cultural memory and, in doing so, allows them to be reassessed and analysed. Above all, the great aesthetic effect of his works, which results from the contrast between deep dark and glistening lights and from his precise drawing technique, appeals to the emotions and evaluations of each of the catastrophes that are stored in our memory. Perhaps it just reinforces them as well: “The beauty of the atomic explosion”, writes Anne-Marie Bonnet in the Wiesbaden catalogue, “does not reduce its terrifying force of destruction; on the contrary, it intensifies its inconceivable brutality”.

“Images impart ideas, transport emotions, are emotionally charged”, writes Lea Schäfer in her contribution, meaning the works that are drawn based on originals. However, this applies no less to abstract art, according to Niels Ohlsen in his text about Elsner’s next large group of works, the abstract watercolour with the series title “Just Watercolors” (Fig. 16–24 ), in which “the artwork goes from being the narrative object to being part of the experienced reality”. For this reason, the exhibition in Wiesbaden, curated by Andreas Henning and Lea Schäfer, confronts the drawings in question and the abstract watercolour by placing them directly next to one another as this allows congruences and differences in coloured differentiations, progressions and structures, in the discovery of contrast between darkness and radiant light, the mastery of the large formats and the paper textures to be studied using different themes and techniques.

“When we look at Slawomir Elsner’s watercolours, it is the wafer-thin layers, deep colour spaces that invite us to dive in, and it is the sharp drying edges, imperceptible compactions of the pigments that immediately attract our attention and won’t leave us alone”, writes Ohlsen in the catalogue. The artist stretches out moist sheets of large-format handmade paper and paints the watery pigment solution in the respective colours in broad layers using a flat brush. A more and more intense and deep saturation is achieved by applying further layers of the transparent, that is to say translucent colours, onto the paper, which has to be wetted again and again, often in more than a hundred passes. The whole process requires an intensive knowledge of the papers, the paint solutions, the drying processes and the mechanical work processes because errors, such as rips in the paper or drops on the already dried layers, cannot be reversed. The result is image plates that have a high degree of radiance but are still translucent, as are otherwise known from the glazing technique used in the Old Master’s oil paintings which consist of multiple layers.

Often underrated in general observation, watercolour painting is one of the most complicated artistic techniques. In controlling the colour density, the wet progressions, the transparent colour overlaps and the drying of the paper that contracts and undulates at the end, the expressionists, particularly Emil Nolde, showed extreme mastery. Of course, we know of tours de force in this technique, from Albrecht Dürer, William Turner to Paul Cézanne and Paul Klee right up to Maria Lassnig. But still, in the last one hundred years, coloured-pencil drawing and watercolour painting are more likely to be found in academic art education. These techniques, which have recently been neglected in professional art at the highest level and in a large format, are brought to life by Elsner so that they can be experienced sensually again.

In his watercolours, sometimes in wall-filling formats, Elsner creates abstract colour spaces, which vary a shade or two (not necessarily complementary) colours in lightness, density and progressions (Fig. 16–18 ), thematise centred clouds of light or horizons (Fig. 19–20 ) or orient themselves on the spectrum of the colour wheel (Fig. 21–23 ). But the artist also brings other colour combinations and light constellations into the consciousness again. With clearly visible (or surprisingly also completely invisible ) footprints of the artistic processes, Elsner adds new insights values, “experienced reality”, to the experiences derived from nature. Whoever connects specific colours or their combinations, especially in the intensity presented by Elsner, with feelings and emotions, can invoke Goethe’s “theory of colours” and its repercussions in modern colour psychology.

Parallels with the colour-field painting of the American artists of the 1950s and 1960s, such as Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko or Ad Reinhardt, or the German painters Gotthard Graubner and Rupprecht Geiger, cannot be ignored. However, we can connect numerous differentiated, content-based approaches and other artistic techniques, which have only a peripheral link to those of Elsner, to all forerunners, which all dealt with oil painting and, like Geiger, with screen printing. If Elsner is compared with Geiger for example, in his large-format paintings we can also find colour and light displacements and dynamic colour spaces, which, however, in terms of content, correlate to mental implications, such as power, energy, love, warmth and strength. The print areas of Geiger’s serigraphies are so sensitive that touching them destroys their integrity. As far as the technique is concerned, Elsner’s watercolours here are more worldly, more haptic and gripping without losing their aesthetic differentiation, radiance and intellectuality. The sixteen pieces displayed in the exhibition belong to one of his most extensive groups of works, which has been developed since 2015, and, according to the catalogue raisonné, currently comprises over ninety works of different formats.

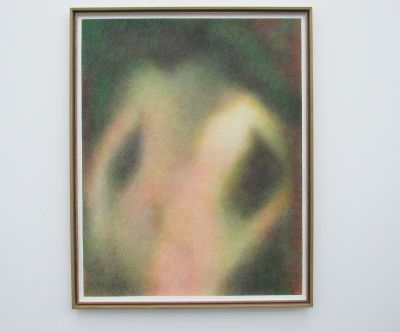

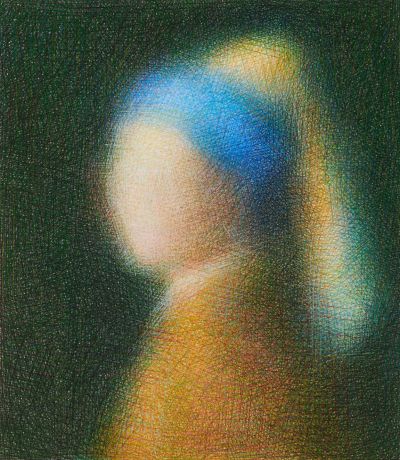

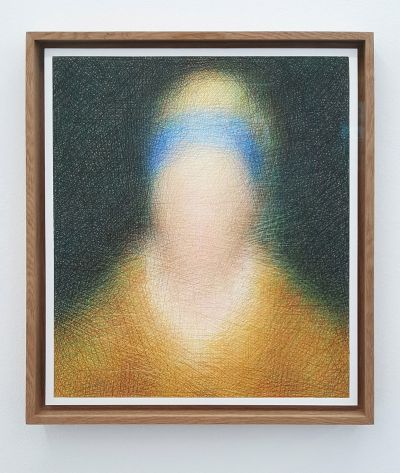

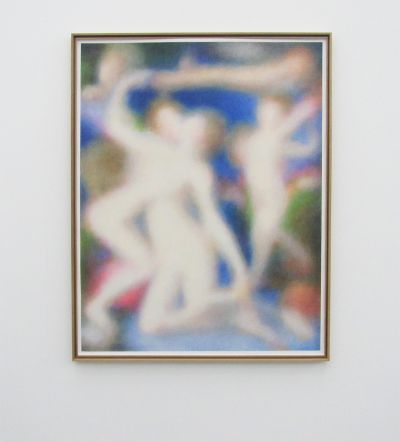

In 2014 and based on older studies, Elsner began to carry out artistic analyses of famous paintings from European and American museums in the form of coloured-pencil drawings, which had the same format as the corresponding oil paintings (Fig. 24–33 ). He does not, however, copy the respective subject and the narrative details, but instead conveys the colour distribution and the light direction of the originals to exceptionally blurred looking fabric comprising fine coloured lines. It is this group of works which the exhibition “Precision and Chance” has to thank for its name and about which Anne-Marie Bonnet ,in her catalogue article “Paradoxien der Schönheit” [Paradoxes of Beauty], quite rightly asks what actually is exact or “precise” about them: “It is more like a mesh, a grid, a thick fabric of strokes in which there are no individual, characteristic or contouring lines, as we are used to in drawings. Although each stroke is sharp, it does not signify anything on its own, only unfolding its effect in interaction with other strokes, with a different colour, placed differently; this is how diffuse colour moods, changing nuances arise. No colour is used, instead colour and light zones are created.”

This series, which has the overall title “Imaginary Memory” and which most recently comprised 144 works, seventeen of which are shown in the exhibition, is the most comprehensive of Elsner’s works to date. This series of works had already been the impetus for previous exhibitions. In 2015, in the Protestant training centre Hospitalhof in Stuttgart under the title “Nichts ist wie es scheint” [Nothing is as it seems], Elsner exhibited works which dealt with works of art in the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart: the coloured-pencil drawing “Portrait of Agnes von Hayn, née von Rabenstein” (2015) after the painting by Lucas Cranach the Younger and a monumental wall mural comprising wall paints and paper after the four-part “Herrenberg Altarpiece” by Jerg Ratgeb. As a summer guest for a thirty-piece exhibition in the Museen Böttcherstraße in Bremen, which also included drawings about the World Trade Center, he worked on six Cranach paintings (of the Elder and of the Younger) from the collection in the Ludwig-Roselius-Museums under the title “Cranach²”. His drawing, “Der Turm der blauen Pferde” [The Tower of the Blue Horses] (2016) after Franz Marc, could be seen in the exhibition “Vermisst. Der Turm der blauen Pferde von Franz Marc. Zeitgenössische Künstler auf der Suche nach einem verschollenen Meisterwerk” in the Staatlichen Graphischen Sammlung Munich, in which collection it can still be found today. In the exhibition “Comeback. Kunsthistorische Renaissancen“ at the Kunsthalle Tübingen in 2019, Elsner was represented by his work “Madonna im Grünen” [Madonna of the Meadow] after the original by Raffael in the Kunsthistorischen Museum Vienna. In 2020, the Lenbachhaus in Munich invited the artist to tackle the two central paintings from the field of the Expressionist group of artists in the Blauer Reiter Collection, namely with the portraits of the dancer Alexander Sacharoff by Marianne von Werefkin and by Alexej von Jawlensky.

Even the Museum Wiesbaden, on the occasion of Elsner’s latest exhibition, requested that he work with the paintings from the exhibition collection: “Spanish Woman (Head of a Woman with Grey Background)” (cover picture , Fig. 24–25 ) and “Lady with a Fan” by Jawlensky and his self-portrait of 1912 (Fig. 26 ), then with the “Lovers” by Otto Mueller (Fig. 27–28 ) and “The Butterfly Catcher” by Carl Spitzweg (Fig. 29 ), with it being left to the artist to make the final selection. Almost all of the paintings selected by Elsner over the years for the “Imaginary Memory” series are popular worldwide, have been depicted hundreds of times and are without doubt part of mankind’s cultural heritage. Elsner’s renderings, drawn from illustrations or photographs, appeal in their entirety to the cultural memory and test what we have preserved in our memory. The titles do, of course, provide a helpful hint and that definitely succeeds with Bronzino’s “Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time” (Fig. 32 ), Mueller’s “Lovers” (Fig. 27 ) and especially Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring” (Fig. 30 ). But it can also go wrong, as Anne-Marie Bonnet wrote upon seeing Elsner’s drawing “Der Turm der blauen Pferde” after Franz Marc “initially [I] took [it] to be a picture of the Madonna” (Fig. 28 ) and who “after becoming aware of the title (had) many ‘lightbulb moments’ of seeing-knowledge-recognition which had their own appeal”.

The artist himself fuels such “lightbulb moments” by contriving, for a small series entitled “Imaginary Present”, a “Girl with Pearl Earrings (2018, Fig. 31 ), this time in a view from the front. Of course, she should now wear two pieces of jewellery – but only in the title because, as we know, his works lack details. In 2020, he added the “Bildnis einer bekannten Dame” [Portrait of a Well Known Lady] to the “Portrait of an Unknown Young Gentleman” (2017, after Ludger tom Ring the Younger) (not shown in the exhibition) and almost casually hung the drawing, which was based on a private photo, next to his works based on famous artworks in the exhibition in Wiesbaden (Fig. 25 ). According to Bonnet, “If the subject remains ambiguous even after the title is known, then the toxicity, so to speak, on/in Elsner’s graphic pictorial strategy unfolds”.

Bonnet analyses Elsner’s evocations and believes that his graphical works in the early catastrophe subjects “remind us that each picture is a challenge to visualise an image, an image of one’s own expectations and willingness to have a visual experience and insight. How much do we project and how much do we recognise? How do we look at a poster and how do we look at a Rubens? How much is cultural convention and how much is our own authentic experience?” The previous museum stops and the Wiesbaden exhibition have gone along with Elsner’s strategy of appealing to the collective memory by keeping a substantial spatial distance between the historical originals and his works. It goes without saying though that, during the exhibition in the Hospitalhof in Stuttgart, the historical role models continued to hang in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart. Following an earlier exhibition in the Lenbachhaus, Marianne von Werefkin’s “Tänzer Alexander Sacharoff” had long found itself back in its true home in Ascona and, in Wiesbaden too, there is quite a distance between Elsner’s exhibition and the museum’s collection.

Several series of coloured-pencil drawings, which the artist worked on from 2006 after Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills” and entitled “Populaires”, “Displaced”, “Odyssee” and “Selfshots” and which are based on photographs and have different conceptual implications, have not been considered for the Wiesbaden exhibition. They were shown in 2012 to mark the awarding of the Falkenrot Prize to the artist in the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin and have been documented in the accompanying catalogue. In 2006, the Galerie Gebr. Lehmann in Dresden showed Elsner’s oil paintings from the “Panorama” series, for which no less than 130 pictures in various sizes, from cabinet pieces to wall-filling formats, were produced in the same year; two years later an extensive catalogue was published as well. In this series, the artist turned magazine photos from the year of his birth 1976 and taken from the popular Kattowice magazine “Panorama”, into oil paintings. What was special about the magazine images was that they had been cut out and reprinted from Western press products by the editors to contrast the socialist reality in Poland with a certain cosmopolitan outlook, which peaked with the pin-up girls, the “Girls of the week”, which were also reproduced. As the Warsaw art historian, publicist and gallery owner Łukasz Gorczyca writes in the catalogue, in his paintings Elsner did not just document the graphic and colour imperfections of these reprints; above all he captured “the roots and political conditions of contemporary visual culture” in an image. Elsner analysed “how to this day graphical and political deformations make their mark on our consciousness, our sensibility and our historical memory”.

The Wiesbaden exhibition goes hand in hand with the awarding of the Otto Ritschl Prize to Sławomir Elsner in 2020. The prize is awarded by the Museumsverein Ritschl e.V. in collaboration with the museum and also includes prize money and the exhibition organised by the museum. The prize is awarded in memory of the author and painter Otto Ritschl (1885–1976), who was based in Wiesbaden and was an excellent exponent of abstract art. It is given to notable artists nationwide whose work “has as its subject matter colour and colour space” and was previous awarded to Gotthard Graubner in 2001, to Ulrich Erben in 2003, to Kazuo Katase in 2009 and to Katharina Grosse in 2015. On the occasion of the award ceremony, Andreas Henning, Director of the Museums Wiesbaden and jury member, stated: I have been observing the high level of artistic talent and the impressive consistency with which Elsner turns his attention to the basic artistic phenomena and, at the same time, develops a very independent position in the contemporary art scene.”

Axel Feuß, February 2022

Literature:

Slawomir Elsner. Präzision und Unschärfe / Precision and Chance, published by Andreas Henning and Lea Schäfer, Exhibition catalogue of Museum Wiesbaden and Dr. Cantz’sche Verlagsgesellschaft, Berlin, 2021 (with essays by Lea Schäfer: Zur Aneignung des visuellen Gedächtnisses – Bilddiskurse im Frühwerk von Slawomir Elsner; Anne-Marie Bonnet: Paradoxien der Schönheit – Slawomir Elsners zeichnerisch-malerische Evokationen; Nils Ohlsen: Lichtatem – Slawomir Elsners abstrakte Aquarelle; 144 pages, German/English)

Sławomir Elsner. Coloured Pencil Drawings. Falkenrot Prize 2012, Exhibition catalogue of the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin 2012 (with text by Raimar Stange: Windows on the World. Kunst nach Nine-Eleven; Natalie de Ligt: Populaires. Bilder entstehen im Kopf; Esther Ruelfs: Stills. An den Rändern des Mediums; Chris Lünsmann: Phantome. Die im Dunkeln sieht man doch; Karin Pernegger: Selfshots. Die Löschung des Selbstbildnisses; 96 pages, German/English)

Sławomir Elsner. Panorama, Exhibition catalogue of the Galerie Gebr. Lehmann, Dresden/Berlin, Cologne: Dumont-Buchverlag, 2008 (with text by Łukasz Gorczyca: Panorama, 1976; 158 pages, Polish/German/English)

Internet:

Sławomir Elsner’s Curriculum Vitae on the Galerie Gebr. Lehmann website, Dresden/Berlin, last completed up to 2021, https://www.galerie-gebr-lehmann.de/artists/slawomir-elsner/cv/

Exhibition in the Hospitalhof Stuttgart, 2015, https://www.hospitalhof.de/kunst/ausstellungen-archiv/slawomir-elsner-nichts-ist-wie-es-scheint/

Exhibition as a summer guest in Museen Böttcherstraße in Bremen in 2017, https://www.museen-boettcherstrasse.de/ausstellungen/sommergast-2017-slawomir-elsner/

Exhibition in the Blauer Reiter Collection at the Lenbachhaus Munich 2020, https://www.lenbachhaus.de/entdecken/ausstellungen/detail/slawomir-elsner

Exhibition “Precision and Chance” in the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021/22, https://museum-wiesbaden.de/slawomir-elsner

Interview with Ritschl prize winner Sławomir Elsner on the website of the Freunde des Museums Wiesbaden, 2021, https://www.freunde-museum-wiesbaden.de/news/interview-mit-slawomir-elsner/

(All links were last accessed in February 2021.)

![Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913) Sławomir Elsner at the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden, 2021 (Alexej von Jawlensky in the background: Spanierin [Spanish Lady], 1913)](/sites/default/files/styles/width_800px/public/Titelbild_23.jpg?itok=31IcSIIx)