Józef Brandt

Mediathek Sorted

Józef Brandt – A Polish painter prince in Munich

In earlier centuries, the studios of artists were a one-to-one reflection of their social status. Anyone who who was still young or artistically and financially unsuccessful, like Marcello and Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini's opera "La Bohème", had to settle for a freezing attic above the city roofs. Artists who had no heating had to be prepared for the worst, in this case according to the outline of the opera (which takes place around the year 1830 and premiered in 1896), with the death from consumption of their great love, Mimi. For successful artists, however, their studio was not only their daily workplace, but also the place where they received students, fellow artists, collectors, high-ranking personalities and travellers from all over the world. One famous example is the studio of the Viennese history painter Hans Makart (1840-1884), who after his return from Rome in 1872 set up a new painting studio in Vienna and furnished it lavishly with heavy wall hangings, tall, elaborately carved furniture, carpets, brass objects, antiques, weapons and huge bouquets of dried flowers and palm fronds. Here he welcomed the Austrian Empress Elisabeth, threw parties and greeted groups of tourists during the afternoon.

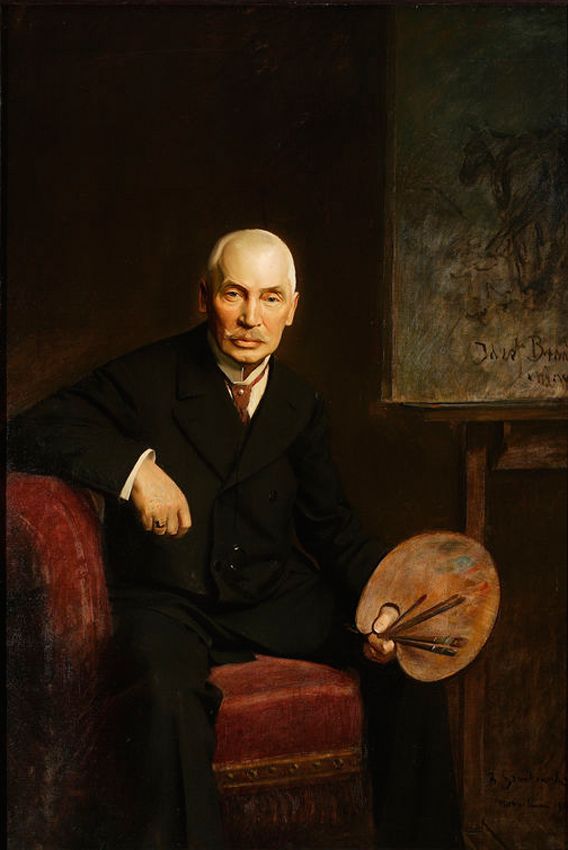

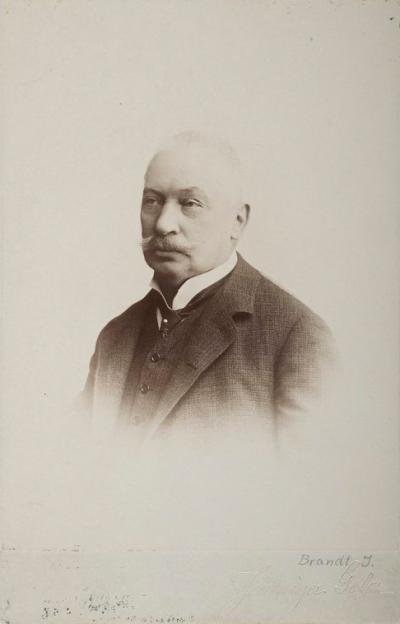

It is therefore no coincidence that three years later a Polish painter in Munich, Józef Brandt (fig. 1), who called himself Josef (occasionally Joseph), von Brandt on account of his Polish aristocratic background, set up a very similar studio after working for twelve years on dramatic equestrian, battle and Cossack paintings, and achieved a prestigious social position in the capital of the Kingdom of Bavaria. He and Makart were almost the same age and studied under the same professor: Makart was born in Salzburg in 1840 and, after initial semesters at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, moved to the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1860 to join the history painter Carl Theodor von Piloty (1826-1886). Brandt was born in 1841 and enrolled in the Munich Academy in 1863 after studying engineering in Paris. Somewhat later he studied under Piloty, but mostly in Franz Adam's private studios (1815-1886) and in Theodor Horschelt's (1829-1871) watercolour painting courses.

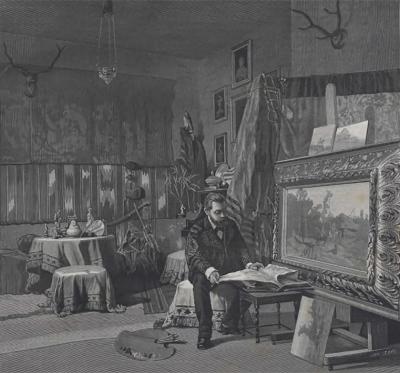

Brandt's studio also became a public attraction. In the years before, he had collected props and antiques needed as models for his paintings, on journeys through Poland and the Ukraine. He acquired them from other artists or impoverished aristocratic families and occasionally paid for them with paintings.[1] This resulted in an extensive collection of Turkish tents, Persian carpets, antique curtains and fabrics, oriental seating and tables, Renaissance and Baroque furniture, weapons used by Polish hussars, sabres, pistols, horse saddles and harnesses, pieces of armour, helmets and shields as well as musical instruments and costumes with their corresponding figures. In 1874/75 he moved into a spacious studio at Schwanthalerstraße 19 in the Ludwigsvorstadt,[2] a suburb not far from Karlsplatz and the old part of Munich, which he decorated with these artefacts, used them as models for his painting and stored them there. The space was originally a five-room apartment on the third floor of a newly built apartment building, which he rebuilt and in which he was to work for the next forty years.

Thanks to contemporary reports, including letters from Brandt himself, we know a great deal about the furnishings, the function of the individual rooms and what took place there. When he was nine years old Andrzej Daszewski, one of his grandsons, saw the studio and wrote about it later.[3] On one side of the corridor there were two painting studios. The larger one was equipped with oriental sofas, a table with inlays and furniture from the 16th and 17th centuries. It was decorated with numerous weapons and armour. The walls were covered with a Turkish tent and there was a Persian rug on the floor. Easels and shelves for the paint and the brushes served as painting utensils. The painter Władysław Szerner (1836-1915), a friend of Brandt, worked for many years in the second studio, where Brandt stored his armour and musical instruments. When Brandt was away - and this was mostly the case as the Polish painter Anna Bilińska (1857-1893) wrote about a trip to Munich in 1882 - Szerner admitted visitors and acted as an official curator of the collection.[4] Opposite there was a room for storing costumes, graphics and books, while another room housed an exemplary arsenal of historical weapons, armour and regimental banners from various European countries. The walls there were also covered with a Turkish tent.

Like Makart, Brandt also used his studio for celebrations and welcoming members of the royal family. In a letter to his mother in Poland in 1876, he wrote that he had celebrated his name day in the studio with pupils and artist friends (especially from the Polish colony), like Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz and Szerner. On the following Monday Prince Luitpold had visited him personally to offer him his best wishes. At the carnival celebration of the Munich artists under the motto "A Court Festivity for Charles V.", in which Makart and members of the royal family were also involved, he caused a great sensation by equipping a Turkish troupe with props from his studio.[5]

Prince Luitpold of Bavaria (1821-1912), who had been Prince Regent since 1886, was known for his love of paintings. His unexpected visits to the studios, including those of young artists, through whom he got to know a large part of the Munich artists' community, were an early passion that he retained for decades and which became legendary during the years of his reign.[6] As Prince Regent he promoted the arts by creating foundations, and constructing numerous cultural buildings like the new building for the Academy of Arts (1886) and the Bavarian National Museum (1893-1900). He was also an important art collector. In an almost inflationary manner he appointed artists as professors and elevated them to the rank of nobility by awarding them the Bavarian Order of Merit. Two-thirds of the newly appointed academy professors held nobility titles.[7]

On the one hand Brandt's artistic success, his lavishly furnished studio, the collection associated with it, and his proximity to the royal family, enabled him to claim a social position similar to that of Makart, the so-called "artists' prince" of the era; and on the other, to the classical Munich "painter-prince" Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904), also a student of Piloty, Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920) and Franz von Stuck (1863-1928). While Brandt had an aristocratic background, Makart, Lenbach and Stuck all came from simple families. Makart was the son of a room keeper at Salzburg's Mirabell Castle, Lenbach was the son of a master builder from Schrobenhausen, Stuck was a miller's son from Tettenweis in the district of Passau. Kaulbach's father was the history painter Friedrich Kaulbach, a cousin of the director of the Munich Art Academy, Wilhelm von Kaulbach. But it was neither an inherited nor a conferred aristocratic title that made the painters "artist princes", but the visit of the Prince Regent to their studios,[8] where the sovereign and the "aristocrat of genius", as the art writer Friedrich Pecht (1814-1903) described the painter Wilhelm von Kaulbach,[9] could meet on equal terms. The "painter prince" cultivated "contacts with the greats of this world", writes Pecht about Piloty.[10]

Brandt, Lenbach, Kaulbach, Stuck and many other Munich artists of the time orientated themselves around Makart and designed their studios as meeting points for high society.[11] Lenbach opened his studio tor the nobility and passing aristocracy, Kaulbach displayed his art treasures from Tintoretto to Tiepolo during fixed opening hours, and Stuck arranged his painting studio to look like an architectural consecration area. From the 1860s onwards Munich travel guides began to feature the addresses and, in some cases, the opening hours of the artist's studios in order to guide the streams of tourists to the right places. English-speaking guides highlighted Brandt's studio and described its owner as an example of "a particularly successful master of the exotic genre and owner of an out-of-the-ordinary showroom".[12]

In contrast to Brandt, the Germans in Munich lived in representative villas where the studio was the centre of attention. During this time Lenbach 1885, Kaulbach 1887 and Stuck 1898,[13] were given personal aristocratic titles and overwhelmed with orders and offices. However, Brandt did not have to hide behind his colleagues. As early as 1877 he married Helena von Woyciechowski Pruszak/z Woyciechowskich Pruszakowa, owner of the Orońsko estate and a representative manor house [14] fifteen kilometres south-west of the Mazovian town of Radom in the Russian-ruled Poland Congress. From then on he worked there in a painting academy that he organised during the summer months along with other painters from the Polish artists' colony. In 1878 he was appointed honorary professor at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, and in 1898 he was awarded the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art.

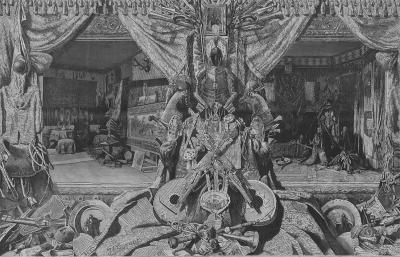

Soon after its opening Brandt's atelier also caused a sensation in Poland. Apparently on the basis of a photograph, Szerner drew a view of the larger studio, with Brandt sitting in front of his easel leafing through an illustrated book, with a palette of paint at his feet. It was published in June 1876 in the Warsaw magazine Kłosy (Engl: Ears, as in wheat) as a wood engraving by the woodcutter Jan Styfi (1841-1921) (fig. 2). In his "Letters from Munich" in the same magazine that October, the Polish writer Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812-1887), who was based in Dresden, described Brandt's studio in detail, as a "truly historical museum".[15] In December the Warsaw magazine Tygodnik Illustrowany (Engl: Illustrated Weekly) published a view of the two larger studio rooms, again drawn by Szerner, but this time without the painter. It was accompanied by an extensive article on Brandt's work.[16] Placed on a double-page spread, Paweł Boczkowski's (1860-1905) engraved wooden sheet showed a splendid frame decorated with objects from the collection, crowned by a picture of the Black Madonna with a halo of sabres and pistols.[17] (fig. 3)

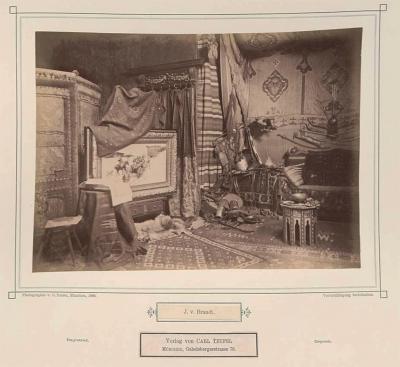

In 1889, the Munich photographer Carl Teufel (1845-1912), - a specialist in interior photography and photo templates for painters of landscapes, animals, horse-drawn carriages, farms and scenes from the working world - photographed around 240 "Studios of Munich artists" and published them in an alphabetically arranged three-volume work: Brandt's studio was also included.[18] (fig. 4) In 1890 one of the three photos taken at Brant's studio appeared in the Krakow periodical Świat (Engl. World),[19] another in 1899 in the periodical Tygodnik Illustrowany.[20] (fig. 5) In 1903 in his article published in the magazine Życie i Sztuka (Engl. Life and Art) and entitled "A visit to Józef Brandt in Munich", the Polish painter and art critic Władysław Wankie (1860-1925) - he came to Munich to study in 1882 and was a member of the Polish artists' circle around Brandt for twenty years [21] - wrote that "few people in Poland possess such a wealth of historical objects as he does".[22] In 1920, five years after Brandt's death, all the pieces of equipment in his studio (there were more than 330), were taken to the National Museum in Warsaw, according to his wishes.[23]

Józef Stanisław Brandt grew up in a wealthy aristocratic Polish family, where academic studies, cultural education in the form of music, literature and fine arts and the possession of agricultural goods were taken for granted. He was born on 11th February 1841 in the small town of Szczebrzeszyn, fifty kilometres south-east of Lublin, where his father worked as chief physician in a hospital. His grandfather, Franciszek Antoni (1777-1837), a physician and professor of anatomy, had earned an extremely distinguished record in Warsaw's health care system, and been elevated to the nobility. During his high school and university years, his father Alfons Jan (1812-1846), belonged to a circle of young aristocrats around the composer Frédéric Chopin. He also became a doctor of medicine and surgery, but died at the age of 34 during a typhoid epidemic when Józef was five years old. His mother, Anna Krystyna (1811-1878), raised her son in Warsaw, supported by her brother Stanisław Lessel, the owner of the estate and a horse lover, her brother-in-law, the doctor Adam Bogumił Helbich, and Józef's godfather, Count Andrzej Zamoyski. His mother was already a talented amateur painter; and his uncle Lessel also painted, kept up close contacts with artists and owned an art collection. Helbich, who leased his Konary estate at Radom to Lessel, was also an art collector. The grandfather on his mother's side, Friedrich/Fryderyk Albert Lessel (1767-1822), an architect from Dresden, was a master builder in Warsaw who designed aristocratic residences and blocks of apartments for the upper-classes.[24]

Józef spent his summer holidays with the Lessels on the Konary estate[25] or on the Orońsko estate with his school friend Aleksander Pruszak (1837-1873), whose father was also a member of the circle around Chopin. Even as a boy he was a passionate rider. He completed his secondary school studies with distinction at the Warsaw Aristocracy Institute (Instytut Szlachecki) in 1858. The following year, Zamoyski sent him to study engineering at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées in Paris, but he abandoned this after one year in order to to study painting. Armed with a letter of recommendation from Lessel he contacted the painter of hunting, battle and horse scenes, Juliusz Kossak (1842-1899), who had studied in Lemberg at the painting school of Jan Maszkowski (1793-1865) and lived in Paris between 1855 and 1860. Together with Kossak he visited the Paris museums and probably received his first painting lessons. He also studied under the historical painter Léon Cogniet (1794-1880) and under his pupil, Henryk Rodakowski (1823-1894) from Lemberg. Together with Kossak he travelled on several occasions to study painting in Wolhynia, Podolia and Bessarabia. In Paris and Warsaw he met the portrait painter Józef Simmler (1823-1868), who was eighteen years his senior, and studied in Munich from 1840 onwards with Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872), among others. Simmler, Kossak and Lessel encouraged Brandt to continue his studies in Munich. The capital of the Kingdom of Bavaria was known for the high quality of its artistic education at the Academy of Fine Arts, for its important art collections and the liberal attitudes of the population. This explains why numerous Poles were studying art in Munich.[26]

In 1862/63 Brandt moved to Munich to study painting in the private studio of the history painter Alexander Strähuber (1814-1882), a pupil of Schnorr von Carolsfeld. On 17th February 1863 he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and like most of the academy's students began his studies in the antiquity class[27], after which he studied under Carl von Piloty, who mainly painted history scenes.[28] But he also found pictures of battles and horses similar to those by Kossak, painted outside the academy by Franz Adam (1815-1886),[29] who arrived in 1860 from Italy to Munich and in whose private studio Brandt received further instruction. He also attended watercolour painting courses given by Theodor Horschelt (1829-1871), who was known for war scenes from Caucasia and Algeria.

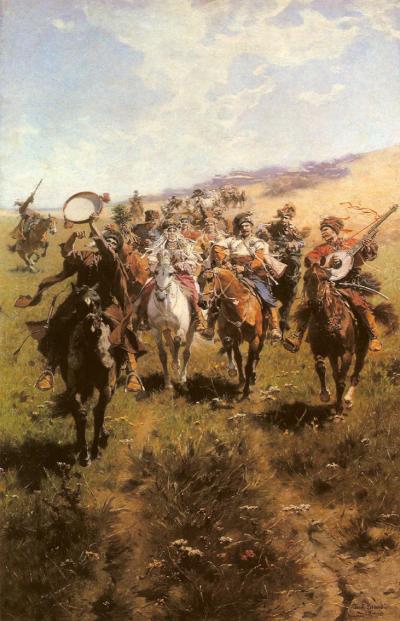

Even at this early stage, Brandt was showing his own works in public. In 1863 he presented his painting “The March of the Lisowskis“ (Pochód Lisowczyków, fig. 6), at the Society of Friends of the Fine Arts in Krakow/Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie. It received so much approval and recognition that the society's board of directors commissioned the Berlin engraver Hermann Droehmer (1820-1890) to reproduce it as an annual gift for the members. The scene shows the Lisowski Cossacks, originally recruited and trained by the Lithuanian nobleman Aleksander Lisowski (around 1580-1616) in operation during the Polish-Ottoman War of 1620-21, a subject which Brandt was to deal with in future paintings. The picture shows that he was already a virtuoso in this genre and had long since outstripped his teacher, Adam, with his concise colourfulness, skilful perspective, the vivid scene and the elegance of the horses.

He also produced genre motifs like “Jews taking their Horses to Market” (ca.1865, fig. 7) and “Polish Peasant's Horse and Carriage” (1865, fig. 8), where the composition and perspective, the characteristics of the horses and the gestures of the characters involved are similar to the previous Cossack painting.[30] Nor is this a battle painting, because the main pictorial elements, apart from its studies of animals, the picturesque costumes and carriages, are really genre motifs. Brandt's continued interest in 17th century themes, the era of the Polish wars, as well as the landscape and folk culture of the Polish border areas, can be attributed to the early influence of Kossak and their joint travels, from which Brandt certainly brought sketches to use in his paintings.

In 1867 he painted his first wall-sized battle painting,"The Battle of Chocim" (fig. 9), which also shows a scene from the Polish-Ottoman War, namely the defence of the Polish fortress against the Turks with the support of the Cossack army in September 1621. At the centre of the scene is the Lithuanian commander Jan Karol Chodkiewicz (1560-1621), who, from his white horse, gives the signal for the attack with a raised staff. The coloured costumes of the cavalry soldiers are once more important motifs in the middle of the detailed depiction of the steppe, the turmoil of battle and the gun smoke.The monumental painting was shown at the Paris World Exhibition in the year it was created and moved Friedrich Pecht to compare it with Theodor Horschelt's paintings of a battle in Caucasia: "Brandt's beautiful painterly talent, (he was a pupil of Adam's), was not so completely successful in portraying the physical aspects of the battle of Choczin. On the other hand, there is a rich and captivating imagination in the composition which equally shows his talent for colour".[32]

In1867 Brandt wrote a letter to Helbich describing his first own painting studio at 23 Schillerstraße in Ludwigsvorstadt, which would become one of the most beautiful in Munich.[32] However, in reality the address was that of Adam's studio, where Brandt apparently rented a room. Kossak, who studied with Adam for another year in Munich in 1868/69, described the situation there in a letter to the Warsaw painter Marcin Olszyński (1829-1904). In the first of the three interconnected studios Adam would teach his students, including Aleksander Gierymski (1850-1901), Kossak himself worked in the second with Aleksander's brother, Maksymilian Gierymski (1646-1874), with Brandt in the third.[33] In 1870 Brandt moved to an apartment in the nearby Landwehrstraße, where he used one room as his studio.[34] In 1871 he registered his address in the next street at 13 Schillerstrasse.[35] This was not far from Schwanthalerstrasse, where he moved into a splendid studio three or four years later: this was to be his final studio. In 1869 he exhibited two paintings at the I. International Art Exhibition in the Royal Glass Palace in Munich.[36] There he was awarded a gold medal for the paintings "A Fair in a Small Town in the region of Krakow" and "Episode from the Thirty Years' War: General-in-Chief Strojnowski presents Archduke Leopold I. with the horses of the Palatine Count on the Rhine, captured by the Polish volunteer forces”.[37] In this exhibition Adam exhibited, among other, a "Retreat from Moscow in 1812" and the painting "During the Battle of Solferino 1859".

During the summer holidays Brandt regularly travelled to Poland to visit his family in Warsaw and Konary, where Helbich and his family had settled in 1867. He first visited his friend Aleksander Pruszak in Galicia, where he had fled after the January uprising in 1863 and met his future wife, Helena von Woyciechowski. Helena and Pruszak were married in 1866 and settled at the estate in Orońsko. Brandt is said to have told friends that If he ever married a woman, it would be Helena. Pruszak's mother, Amelia, loved the presence of artists and ran an artistic and literary salon in Orońsko, where plays and concerts were held alongside discussions. The uncles, Helbich and Lesser, were not the only regular guests here. Brandt also stayed for several days. He is alleged to have set up his first studio for students of painting in Orońsko in 1866. Amelia Pruszak died in 1867, and in 1873 Aleksander passed away at the tender age of 36. After a discreet period of mourning, Brandt married Helena, his friend's widow and owner of the Orońsko estate, in June 1877.[38]

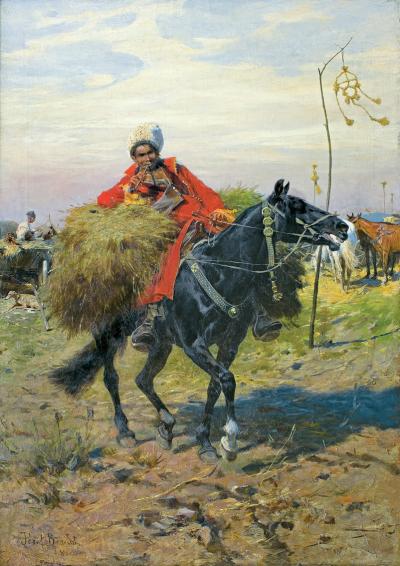

Genre motifs seem to have been by far the main themes in Brandt's work “Parting” (1867),[39] which shows a Cossack saying farewell to his wife on the edge of a village; “Grazing Horses” (1869, fig. 10) with a boy playing music to his sister; “A Break in a Small Town” (circa 1870, fig. 12) and “In the Tavern” (fig. 13), where both scenes portray horses at a streetside inn; “Waiting for the Boat” (1871, fig. 15), which shows peasants and traders resting with their waggons and horses before crosssing a river; “A Break in the Steppe” (undated, fig. 20); and “Cossack with a Girl at the Fountain” (1875),[40] “The Market in Balta” (1875),[41] “Horse Breeding” (1876, fig. 22) and “A Polish Horseman with his Horse at the Toll House” (1877, fig. 23) reveal the different themes. The existing paintings and sketches are, however, only a selection of numerous similar and varied motifs, as can be seen in contemporary photographs and reproductions. There are horses in every picture. Most scenes show a departure, a journey through the steppe, to the market place, to the next town or a stop on the way. It is not always clear whether the subjects are farmers, soldiers returning home or scattered soldiers, Cossacks in peacetime or during military operations.

Nor was Brandt interested in heroic acts or the glorification of historical events, as is the case with other German history painters. In addition to the detailed depiction of the landscape (fig. 21), he was particularly interested in the everyday life of the soldiers: the arduous journey of a cavalry on the return from the battle of Vienna (1869, fig. 11), a break by the campfire (1873, fig. 16), or a patrol by the river (1873)[42]; a Cossack's lonely night watch (1878, fig. 24), a small skirmish with the Swedes in a dramatic forest landscape (1878)[43], and also picturesque scenes like that in “A Raid by the River” (1874, fig. 18), which featured uniforms and head coverings. They include all kinds of horses, a packed wagon stuck in a river bed that needs to be set free, and breathtaking perspectives. Flags, lances and wildly beaten musical instruments enliven a welcoming procession of Cossacks on the steppe (1874, fig. 19). Brandt's interest in picturesque details went far beyond the folkloristic genre cultivated by his fellow German painters.

Brandt not only painted small and medium format works. In the follow-up to the "Battle of Chocim" (fig. 8), he also created monumental wall-filling paintings at lengthy intervals. These included the battle scenes "Czarniecki in the Battle of Kolding" (1870), the "Battle of Vienna" (1873) and the "Liberation of the Prisoners" (1878), as well as the - now lost - wall-filling painting "Market in Balta" (1875). Here it must be added that the artist occasionally changed the width of his canvases by one metre to four metres. The "Battle of Kolding" (fig. 14) depicts an event from the Second Nordic War, during which Polish troops under the leadership of the commander Stefan Czarniecki (1599-1665) came to the aid of the Danes who were under attack from Sweden. In December 1658 the Polish forces conquered the island of Alsen and finally Kolding Castle. Here too, Brandt does not depict a heroic victory. Instead, he portrays the efforts of the soldiers, who are trying to reach the snow-covered shore from their ships in the Koldingfjord.and from there to get to the top of the castle hill with their horses. The picture is dominated by red uniforms, flags and horse blankets against an atmospheric background consisting of the castle and a snowy fjord landscape on a freezing, misty winter morning.

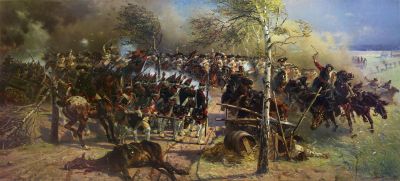

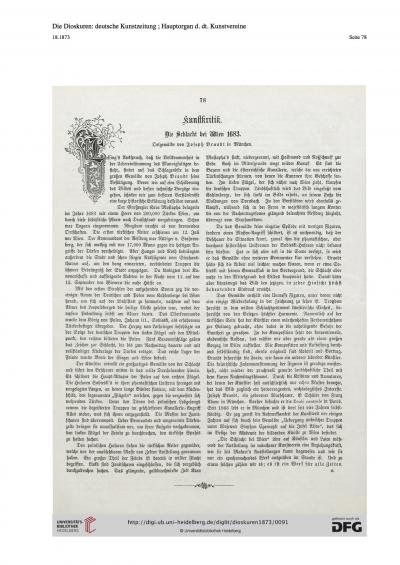

The "Battle of Vienna" (1873, fig. 17) shows the allied German-Polish army led by the Polish King Jan III Sobieski (1629-1696) attacking the Turks on 12th September 1683, after the Austrian capital had been under siege for months and faced capitulation. The painter dramatically illuminates the right half of the scene, with Turks in colourful uniforms fleeing from the attacking Polish hussars who have overrun their tents. The painting was shown in its year of origin at the Vienna World Exhibition 1873[44] and subsequently in the rooms of the Munich Art Society, where it was greeted with extensive, enthusiastic reviews. The newsletter of the German art associations, "Die Dioskuren", wrote that the painter had earlier drawn attention to himself with his painting "Polish troops under Vojewod Stephan Czarnetzki crossing to the island of Alsen", which has now passed into the possession of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. "The Battle of Vienna" now exerts an attraction on both artists and laymen[...] the like of which has been virtually unheard of since Makart's exhibitions. This is something of which only an epoch-making work is capable. And we count it as such; it is a work for all time.“[45] (see PDF)

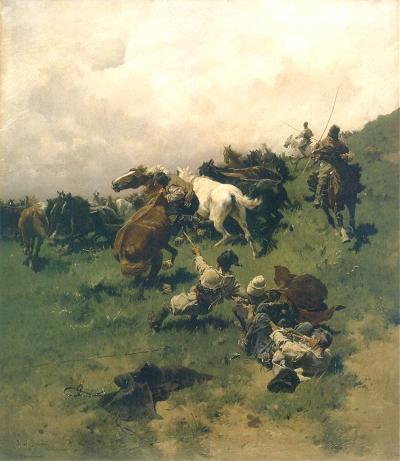

The painting entitled the "Liberation of Prisoners" (1878, fig. 25), depicts an event dating back to the time of the invasion of the Crimean Tatars in Poland-Lithuania in the spring of 1624. This was the battle of Martynów, during which General Stanisław Koniecpolski (1590/94-1646) liberated Polish prisoners of war from the threat of slavery by the Tatars in the Ottoman Empire. Brandt's painting places the battle at the centre of the painting and gives it a further accent with the addition of gun smoke. This time, however, he is also interested in the many motifs in the foreground. They show Tatars in oriental dress fleeing from the picture, with their primitive wagons and tents to the right of them. This time not only horses but also packed camels are standing nearby. The painting "Market in Balta" - it is also three metres wide and is only known from photographs - shows a scene from the Ukrainian town founded in the 16th century by Tatars and inhabited by numerous ethnic groups, in a similar, but mirror-inverted, composition. The main motifs on the bare earth in front of a landscape of mills emerging from the morning mist, are busy figures, riders, resting horses and tents covered with colourful carpets; this time on the left edge of the picture.

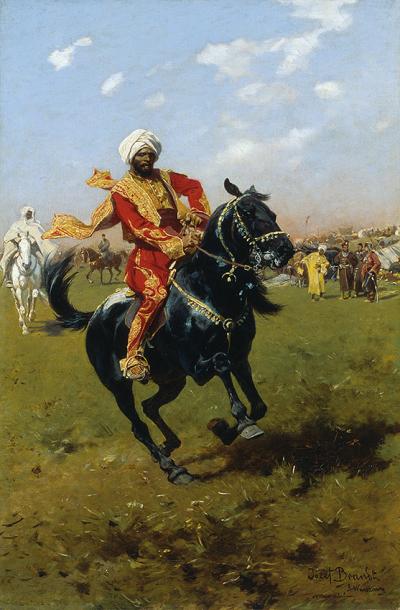

Motifs such as these tempt us to move Brandt nearer to the Orientalists, i. e. Orient painters in France since Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863), in particular Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904); and in Germany, artists like Adolf Schreyer (1828-1899) and Gustav Bauernfeind (1848-1904). Contemporary collectors in Germany, England and the USA valued Brandt's oriental-influenced scenes for their "exoticism”[46] For Brandt and numerous other Polish painters who dealt with the theme of battle and equestrian scenes from the Polish history of the 17th century and the battles of the Poles with Tatars, Turks and the Cossacks, these motifs are a contribution to works of art intended to give the Polish people a sense of identity and pride in their nation. The recollection of the former Polish Aristocratic Republic, which existed between 1569 and 1795 and whose territorial dominion extended to the multi-ethnic border areas with the Ottoman Empire, was intended to point to the goal of establishing a new Polish nation-state during the period of the partitions of Poland.[47]

It is the monumental paintings that justify Brandt's reputation. During the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873 he was awarded an art medal for his "Battle of Vienna". The city of Vienna purchased the painting and presented it to Archduchess Gisela, the daughter of Emperor Franz Joseph I.[48] In 1875, the Berlin National Gallery acquired a small-format oil painting with the title "Podolian Village", "to order", i. e. this was possibly a commissioned work, along with a painting entitled "Tartar Struggle", which, according to its description and size, must be the "Liberation of the Prisoners" (fig. 25).[49] In 1877 Brandt was elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin,[50] and in 1878, as already mentioned, he was made an honorary Professor at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. The small and medium-format paintings that he created in the years between the monumental paintings enabled wealthy buyers to purchase motifs from the major themes of the celebrated painter, which had become well-known to the general public, and display them in their homes.

As a result of his artistic success, his social status and not least the opening of his splendid studio in Schwanthalerstraße, Brandt became the main focus of attraction in the Munich “Poland colony”.[51] By this I mean those Polish artists who emigrated to Munich from 1828 onwards (but above all since the January Uprising in 1863), to study at the Academy of Fine Arts and under private teachers in the city. Between 1863 and 1875, more than eighty Poles were admitted to the Munich Academy. Brandt proved to be not only sociable, but also hospitable and helpful to younger students arriving from Poland. Since he also had a talent for teaching, he soon established an unofficial painting school in his studio. For a time his students included Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz, Jan Chełmiński, Józef Chełmoński, Michał Gorstkin-Wywiórski, Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski and Franz Roubaud, a native of Odessa, who moved to Munich in 1877 from the drawing school there and later travelled to Caucasia and Uzbekistan. Brandt took special care of Szerner, who had also taken part in the January uprising and arrived in Munich completely impoverished in 1865. Indeed he even went so far as to put him up in his studio.

When young Polish painting students visited the Neue Pinakothek (i. e. the collection of contemporary paintings), they discovered with a touch of patriotism that paintings by three Polish artists, Brandt, Maksymilian Gierymski and Wierusz-Kowalski, were also displayed there. Marian Trzebiński, who matriculated in the Munich Academy in 1893, wrote the following in a letter: “As Poles, we were very pleased to see two paintings by Brandt, which also had Polish language signatures '‚z Warszawy‘ und ‚Monachium‘, not Munich, in a prominent place:. […] Such tolerance gave us an idea of the sensitivity and highly developed culture of the Bavarian people”.[52] The Neue Pinakothek probably purchased one of Brandt's pictures in 1885, the year he painted it. This was a one by two metre, large format painting entitled “Cossack horses in a Snowstorm. A second, smaller picture,"Defence", is undated and like the first, it bears the signature "Józef Brandt z Warszawy, Monachium" (English: from Warsaw, Munich).[53]

Over the years the following artists were a part of Brandt's inner circle of acquaintances: Ludomir Benedyktowicz, Olga Boznańska, Szymon Buchbinder, Franciszek Ejsmond, Julian Fałat, die Brüder Gierymski, Bohdan Kleczyński, Ludwik Kurella, Władysław Malecki, Jan Rosen, Stanisław Szembek etc.etc. Under his influence some of them, like Maksymilian Gierymski, Roubaud and Wierusz-Kowalski were also inspired by Polish folk culture and history. They spent a lot of time together, discussing art, singing to the accompaniment of a piano, celebrating parties and going to cafés with Adam. From time to time (like Brandt from 1874 onwards, alone or in the company of Wierusz-Kowalski, Rosen and Władysław Czachórski), they were also invited to dine with Luitpold of Bavaria and the Royal Family.[54] Artists even lived in the same streets: Maksymilian Gierymski, Benedyktowicz, Wierusz-Kowalski and Kossak like Brandt in Schillerstrasse, Landwehr and Schwanthalerstrasse; others like Fałat and Lucjan Kochanowski in the neighbouring Maxvorstadt and Schwabing.[55] Anton Braith (1836-1905) and Christian Mali (1832-1906) were also closely associated with this circle. Mali's studio was located at 46 Landwehrstrasse, and his legacy contained small-format paintings by Brandt, Maksymilian Gierymski and Czachórski, possibly as reciprocal gifts.[56]

From the outside, too, this group would soon be perceived as a closed "school". In 1888 Pecht wrote the following in his "History of Munich Art in the Nineteenth Century":"Thus the Poles, who were fundamentally different from all other artists, but who shared certain common characteristics closely related to their national character, soon made up a very special category. They were increasingly present in Munich to such an extent that they finally made up a formal “school.”[57] The year before, the Munich magazine “Kunst für Alle” had published an illustration of a palette painted by Polish artists, in which Brandt immortalized himself with a Cossack resting in the steppe. It was also signed "Józef Brandt z Warszawy"[58] (fig. 40) Works by six Polish artists were also found in the collection belonging to Prince Regent Luitpold after his death in 1912: Brandt, Chełmiński, Czachórski, Gorstkin-Wywiórski, Stanisław Grocholski and Wierusz-Kowalski.[59]

Following the marriage of Brandt and Helena Pruszak in 1877, the couple spent the summer months from June to October in Orońsko, and the rest of the year in Munich. Helena brought two children from her first marriage, Maria Magdalena (*1868) and Władysław Aleksander (*1871), whom Brandt lovingly cared for. Two children of their own, Maria Krystyna and Maria Aniela, were born in Orońsko in 1878 and 1880. Maria Aniela was baptized in Munich where her godfather was Prince Luitpold of Bavaria.[60] In Munich, the family lived on the first floor of a block of flats in Barerstrasse in sight of the Neue Pinakothek.[61] The couple took part in the social life of the city and the Polish colony and regularly received friends and acquaintances on Sundays. In Orońsko Brandt led the life of a landlord. He managed his estate in an exemplary manner, built up a cattle and horse breeding business with which he won prizes at agricultural exhibitions, built stables and a smithy, and rode out every afternoon. Brandt's studio was located in the estate orangery where Helena had once played piano.[62] Here he set up courses in open-air painting for his Munich students, painter friends and their pupils. It was not long before it bore an unofficial name: the Free Academy of Orońsko. Its regular guests included Ajdukiewicz, Kazimierz Alchimowicz, Chełmiński, Czachórski, Ejsmond, Józef Kania, Kossak, Apoloniusz Kędzierski (who came here for nine years), Artur Potocki, Rosen, Roubaud, Szerner, Wankie, Wierusz-Kowalski and Marian Zarembski. They did not restrict their activities simply to painting but also went out riding and hunting.[63]

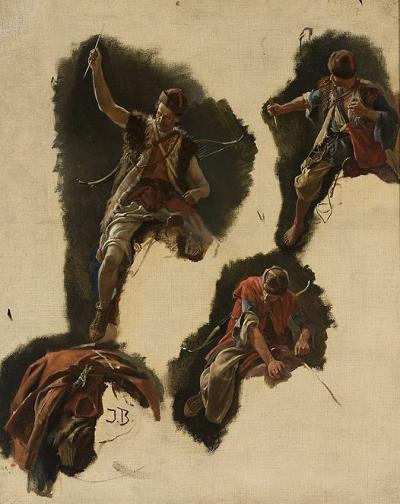

Brandt radically changed his painting style around 1880. The motifs in his military pictures that were primarily dedicated to depicting Zaporozhian cossacks at the lower course of the Dnieper River were now much denser and hence more dramatic (fig. 26, 28, 30, 42). With regard to his more tranquil motifs, this closer view created a narrative style with detailed insights into the wagons and tents, a more precise depiction of costumes and a more intensive characterization of the horses (fig. 27, 29). A study of different Cossack postures (1880, fig. 33) documented the effort to reproduce narrative drama in an anatomically precise manner. Such motifs were replicated in the studio by the painter himself or by models on a wooden horse. The "March with War Booty" (circa 1880, fig. 31) depicts a scene after the Battle of Vienna in 1683, in which Polish hussars lead off colourful and highly picturesquely dressed soldiers in the Ottoman army, including Africans. The detailed portrayal of a camel and an ox-cart, laden with colourful carpets and showing women wearing oriental headdress, illustrates Brandt's closeness to Orientalist painting. His "Cavalry Parade" (fig. 32) and a single "Royal Ensign" (1889, fig. 41) also show Polish hussars after their victory over the Turks at Vienna. This theme also included a later painting: a "Cavalry Attack" on fleeing Ottomans (1898, fig. 53). During the 1890s, he created many pictures of "victorious Cossacks" (1893, fig. 47-49) in the Polish-Ottoman War.

In his genre pictures, Brandt reintroduced into his repertoire hunting scenes which also reflected folk life in the Ukraine (fig. 35,39), but in which he also incorporated his own experiences (fig. 56). In his "Market in Białka" (1885, fig. 36), which might refer to different places in Ukraine (Belka, Bilka, Belika), the viewer is confronted with a rural market in the steppe, where an Oriental trader is offering a saddle selected from a number of colourful carpets, shoes, musical instruments and bowls lying on the ground. Two tradesmen who have arrived on horseback are scrutinising his tableware with interest. A narrative and simultaneously dramatic motif that reoccurs on several occasions is the confrontation between two teams of horses on a bridge (1886, fig. 37) or a dyke (1890, fig. 43), whereby a carriage with several horses driving at speed in the opposite direction is recklessly forcing a peasant's wagon carriage into an embankment beside the river. These also include individual studies (fig. 38) and pictures with only a single “Horse and Cart in Flight” (circa 1900, fig. 55). A large-format "Cossack wedding" on horseback with singing and riders making music (1893, fig. 46) has a folklore character. It was painted at the same time as the corresponding military pictures.

In the 1890s Brandt started to paint wall-filling historical paintings once again. At the beginning of the decade, he painted a picture of "Our Lady of Poczajów" (circa 1890, fig. 44, 45), formerly also known as "The Prayer" or "Our Lady of Armenia". It depicted the faithful in the Ukrainian steppe engaged in evening or morning prayer in front of an image of Our Lady hung on a wagon and illuminated by a lantern. It is said that the icon of the Blessed Mother from the monastery of the Assumption in Poczajów - it originated at the end of the 16th century – was temporarily located in the Armenian cathedral at Kamieniec Podolski, to which it was later returned. Legend has it that it saved the monastery at Poczajów from a siege by Ottoman troops. Here Brandt proves to be an important colourist, who not only characterises the figures and the scene with his sophisticated lighting, but also the natural surroundings. This is also the case with his monumental painting "The Departure of John III. and Marysieńka Sobieska from Wilanów" (1897, fig. 50), which shows the Polish royal couple John III Sobieski (1629-1696) and Maria Kazimiera Sobieska (née de la Grange d' Arquien, 1641-1716), called Marysieńka, illuminated by torches and lanterns, on their departure in a horse-drawn sleigh from the Warsaw Palace in Wilanów. The painting was exhibited at the VII. International Art Exhibition in the Munich Glaspalast in the year it was created, and received favourable reviews from the critics: “J. v. Brandt's magnificent "royal sleigh journey' looks all the more credible because all the characters from King Sobieski to the least significant satellite are so genuinely Polish that one cannot fail to believe in them".[64] A further four-meter-wide version of this motif (fig. 51), for which there is a preliminary study in the Munich Lenbachhaus (fig. 52), was painted in a more summary fashion and lacks the dramatic lighting effects.

Brandt was also widely honoured in the 1880s and 90s. In 1885 the Munich "Polish Colony" celebrated the 25th anniversary of his work as an artist. A committee, including Czachórski and Wierusz-Kowalski, organized the celebrations and prepared a gift of a folder containing drawings and watercolours made by his colleagues. It was reported that Prince Luitpold sent a violet bouquet of gigantic proportions with the numbers designed with flowers " [65] From 1889 onwards, Brandt was a regular exhibitor at the newly established Munich Annual Exhibition, which regarded itself as a competitor to the Paris Salon. On the first of the exhibitions arranged according to nations, Pecht writes: "The Polish contributions are much richer: the majority have admittedly to be attributed to our school, although they all retain their individual character with great energy. Brandt, their leader, offers us a “Departure for the Hunt” in a snow-covered Polish village lane with his usual sparkling animation..."[66]

In the same year, according to the magazine Die Kunst für Alle, a "Joseph v. Brandt album[...] was published by the Photographische Union in Munich. It contained a dozen photographs based on the master's more recent paintings and showing hunting scenes and Cossack life in his homeland and in the Ukraine. The way he reflects their pictorial allure is incomparable.”[67] At the second Munich Annual Exhibition in 1890, Brandt showed “a group of 17th century Cossacks returning home and singing victory songs. Here he displays his usual mastery in the use of splendid colours that are utterly uncorrupted by modern fashions. Even better, because the painting contains more dramatic tension its defence of Polish ihomesteads is full of sparkling liveliness.”[68] In 1891 Brandt turned down an invitation to succeed the first director, Jan Matejko (1838-1893), as the head of the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow.[69] In 1893 he received an award for services to the Bavarian Crown[70], and an award from the Spanish “Order of Isabel the Catholic” for services to science and art. In 1898 he was awarded the Order of Maximilian by Prince Regent Luitpold. “This is a major and rare distinction, given to ten artists at the most”, wrote Czachórski in a letter: “Brandt had not expected it and for this reason he was absolutely astonished. The Order of Maximilian gives him open access to all Court balls and at all receptions there is a table reserved for those who have been decorated thus.”[71] In 1900 Brandt was made an honorary member of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague.

During these years Brandt's paintings were as coveted as they were expensive. Until the turn of the century the Munich gallery Wimmer which represented him, sold most of his works to the USA. After 1900 he switched to Galerie Heinemann. The Georges Petit gallery dealt in his paintings in Paris.[72] From the turn of the century, however, Brandt (fig. 64), who had been painting mainly for the art market for the past twenty years, seemed burnt out. He continued to work as an artist, but for the most part his paintings were repetitions of motifs related to the Battle of Vienna, such as the “Battle for the Turkish Flag”[73] (circa 1905, National Museum in Krakow/Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie) or the wall-filling depiction of “The Bogurodzica Anthem”[74] (1909, National Museum in Breslau/Muzeum Narodowe w Wrocławiu). In doing so he made individual studies of victorious Hussars and Cossacks (fig. 57-59, 62-63). Brandt was now living on the estate at Orońsko amid a large family of children and grandchildren. In 1913 his health began to deteriorate. At the start of the First World War, German soldiers confiscated his horses, requisitioned food and rations and finally plundered all his works of art and everyday objects. In 1915 Russian soldiers forced him to leave the estate and he moved with his family to Radom. Brandt died of pneumonia on 12th June 1915.

Axel Feuß, November 2017

Further reading:

Adolf Rosenberg: Die Münchener Malerschule in ihrer Entwicklung seit 1871, Leipzig 1887, pages 46-48

Friedrich Pecht: Geschichte der Münchener Kunst im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, München 1888, pp. 420-424 („Die Polen, Magyaren und sonstigen Ausländer“), Digitale Sammlungen der Universitätsbibliothek Weimar, Digital version: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:wim2-g-591521 (called up on 21.11.2017)

Janusz Derwojed: Józef Brandt, Warsaw 1969

Münchner Maler im 19. Jahrhundert, Band 1, München 1981, p. 129 f.

Halina Ste̜pień: Artyści polscy w środowisku monachijskim. W latach 1828-1855 (Studia z historii sztuki / Instytut Sztuki, Polska Akademia Nauk, 44), Breslau/Wrocław 1990

Hans-Peter Bühler: Jäger, Kosaken und polnische Reiter. Josef von Brandt, Alfred von Wierusz-Kowalski, Franz Roubaud und der Münchner Polenkreis, Hildesheim/New York, 1993

Halina Ste̜pień / Maria Liczbińska: Artyści polscy w środowisku monachijskim. W latach 1828-1914. Materiały źródłowe (Studia z historii sztuki / Instytut Sztuki, Polska Akademia Nauk, 47), Warschau 1994

Irena Olchowska-Schmidt: Józef Brandt, Krakau 1996

J. Derwojed: Brandt, Józef, in: Saur Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon, Band 13, München/Leipzig 1996, page 641

Halina Ste̜pień: Artyści polscy w środowisku monachijskim. W latach 1856-1914 (Studia z historii sztuki / Instytut Sztuki, Polska Akademia Nauk, 50), Warsaw 2003

Ewa Micke-Broniarek: Józef Brandt (2004), in: culture.pl (Polish/English), http://culture.pl/en/artist/jozef-brandt (called up on 24.11.2017)

Ewa Micke-Broniarek: Józef Brandt, Breslau/Wrocław 2005

Anna Bernat: Józef Brandt (1841-1915), Warsaw 2007

Halina Stępień : Die polnische Künstlerenklave in München (1828-1914), in: zeitenblicke 5 (2006), No. 2, http://www.zeitenblicke.de/2006/2/Stepien/index_html (called up on 24.11.2017)

Eliza Ptaszyńska (ed.): Ateny nad Izarą. Malarstwo monachijskie. Studia i szkice, Suwałki 2012

Jednodniówka – Eintagszeitung. Neuausgabe, herausgegeben von Zbigniew Fałtynowicz / Eliza Ptaszyńska, Muzeum Okręgowe w Suwałkach, Suwałki 2008; simultaneous with the exhibition catalogue “Signatur - anders geschrieben. Anwesenheit polnischer Künstler im Lichte von Archivalien”, Polnisches Kulturzentrum, München 2008

Monika Bartoszek (ed.): Józef Brandt (1841-1915). Między Monachium a Orońskiem/Between Munich and Orońsko, exhibition catalogue Orońsko 2015

Egzotyczna Europa. Kraj urodzenia na płótnach polskich monachijczyków/Das exotische Europa. Heimatvisionen auf den Gemälden der polnischen Künstler in München, Exhibition catalogue Suwałki 2015