Aleksander Gierymski

Mediathek Sorted

Aleksander Gierymski was born on 30th January 1850 in Warsaw, three years after his brother Maksymilian. Their father Józef Gierymski (1800-1875) worked in the military administrative building and was head of the military hospital in Ujazdów. By contrast with his brother who had previously been involved in technical studies and had taken part in the 1863 January uprising, Aleksander was able to follow his artistic leanings and talents directly. At first, like his brother before him, he took drawing lessons for a few months in 1867 under Rafał Hadziewicz (1803-1883) in the Warsaw drawing class (Klasa Rysunkowa), that had been set up in 1865 after the School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych) had been closed down on account of its students participation in the 1863 January uprising. In 1868 he followed his brother to Munich. Here he also trod in his footsteps. In order to improve his drawing skills he matriculated at the Academy of Pictorial Arts in the “antique class” given by Alexander Strähuber (1814-1882), after which he studied under the history painter Hermann Anschütz (1802-1880).

By contrast with Maksymilian, who then pursued his studies in battle and equestrian scenes at the private painting school belonging to Franz Adam (1815-1886), Aleksander remained at the Munich Academy. He took courses under the history painter Johann Georg Hiltensperger (1806-1890), who had made a name for himself with frescoes in the Munich Residenz and the Hofgartenarkaden, before moving on in 1870 to the masterclass of Carl von Piloty (1826-1886). Under Piloty, who had been a professor at the Academy since 1856, the art school had become an important centre for realistic history painting. Józef Brandt (1841-1915), the most important Polish painter in Munich, had studied there since 1863. In 1871 Aleksander travelled with his brother to Venice and Rome. In 1872, along with two other highly valued Polish painters, Władisław Czachórsky und Maurycy Gottlieb, he selected a literary theme for his diploma under Piloty: this was a motif from Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice”, which won him the prize for the best composition. In the following year he painted the court scene from Shakespeare’s comedy, which he displayed in the German art section at the Vienna World Exhibition in 1873. Alongside his brother Maksymilian five other Polish artists were also represented here.

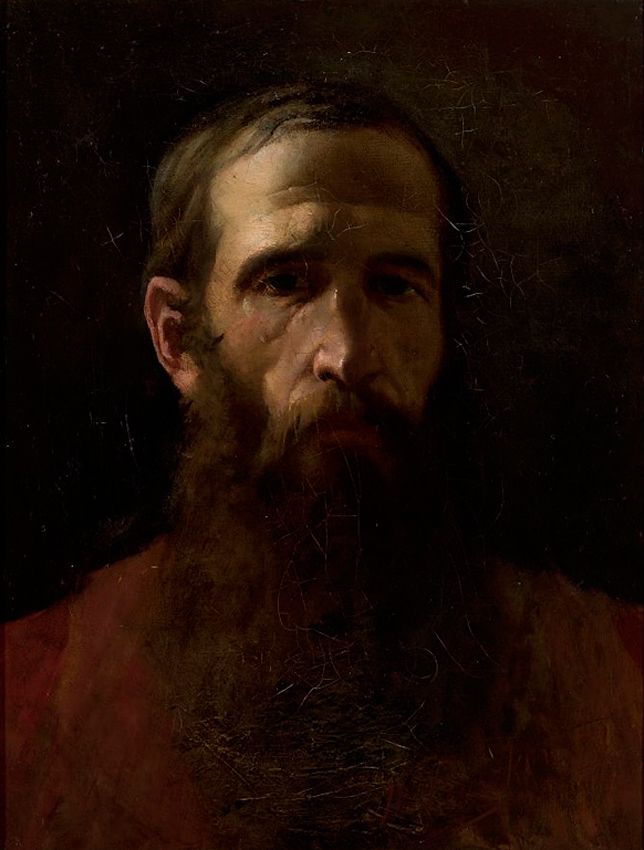

After Maksymilian fell ill with tuberculosis in 1872 and his stays at health resorts in Merano and Bad Reichenhall had brought no improvement to his health, Aleksander accompanied his brother to Rome in the following year in the hope that the climate there would provide him with a cure. Whereas Maksymilian completed his last painting in Rome in 1874, a Parforce Hunt in 18th-century costumes, Aleksander turned to genre motifs in Roman taverns like Playing Morra (Ill. 2). Seen from an academic point of view they are perfect. They show a balanced selection of colours and a particular interest in the use of light. Nonetheless he was reproved by contemporary Polish critics for choosing such trivial scenes. In summer 1874 Maksymilian (presumably accompanied by his brother), travelled to Munich to consult doctors there, after which he took a cure at Bad Reichenhall, where he died in September. Aleksander returned to Rome where he lived and worked until 1879. During this time, in order to counter the criticism of his “popular” motifs, he painted an Italian Siesta with Roman patricians in Renaissance costumes, inspired by masters of the Italian High Renaissance like Titian und Tintoretto.

Aleksander Gierymski travelled on several occasions to Warsaw during his time in Rome, and finally moved back home in spring 1880. Here he completed a painting in 1882 entitled In the Gazebo (Ill. 4). Since 1875 he had been working on a series of detailed studies for the painting in Italy, in which he had tried out arrangements and individual details from nature; above all he was trying to analyse light reflections and the phenomena of colours in the utterly Impressionist oil painting that eventually emerged. This painting remained an exception in Gierymski’s work for a long time, not only on account of its style but also because of the rococo costumes in which his protagonists were attired, as in a scene from a play. This is the sole occasion in which he followed his brother Maksymilian, who had previously become famous in Munich for his scenes of horsemen in 18th-century costume.

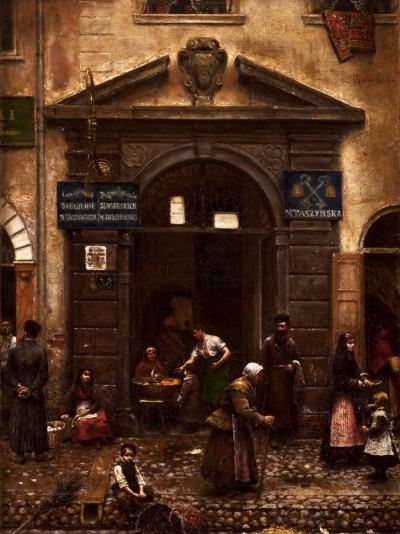

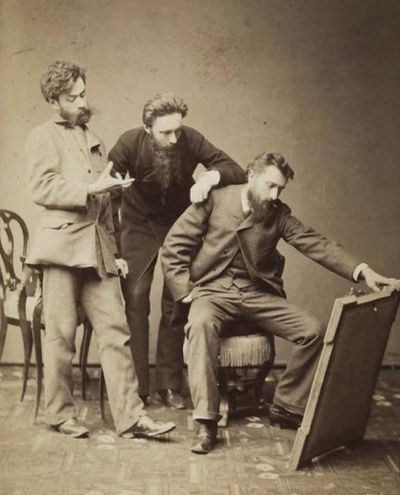

But in the long run the elegant genre of costume pictures in the style of the Renaissance and rococo failed to have any lasting attraction for Gierymski. Instead he turned to the style and content of Realism during his time in Warsaw. This had been propagated by the painter Stanisław Witkiewicz (1851-1915) and the literature, music and theatre critic Antoni Sygietyński (1850-1923) in the Warsaw geographic weekly Wędrowiec (engl. Wanderer). Both men had become acquainted with Gierymski many years before during a long stay in Warsaw (Ill. 7). Now his illustrations began to be published in this periodical. Gierymski mainly concentrated on urban landscapes from the poor quarters of Warsaw, the old city, Powiśle and Solec (Ill. 5, 6). They had an effect that was similar to picture reportages enlivened with everyday scenes. He pinned down portraits of simple folk like the Jewish Woman with Oranges (Ill. 3), religious rituals like the Jewish Trombone Party (Ill. 8) and working situations like the Sand Dredgers on the banks of the Vistula (Ill. 9) with precise observation devoid of any dramatic effects. In 1884 he set out for Vienna to search for a cure to a neurosis (that finally led to mental derangement at the end of his life), and also spent time painting on the Belgian North Sea coast during health cures. In 1885 he returned to Italy once more where he lived for periods in Padua, Venice, Florence and Rome.

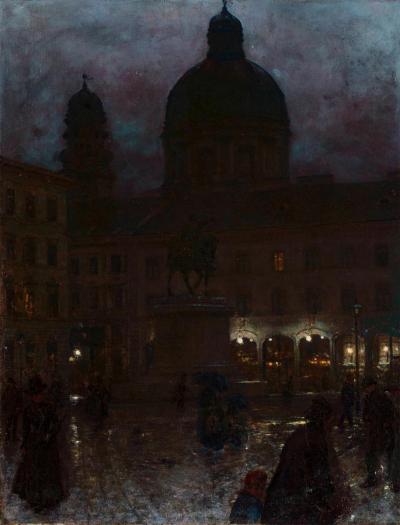

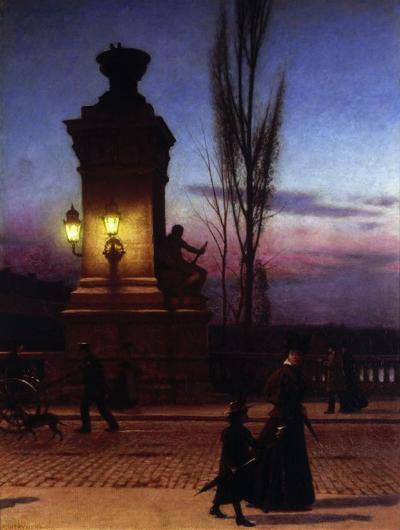

In 1888 Gierymski returned once more to Munich, where he stayed until 1890. Nonetheless he returned to the Bavarian capital on two occasions in 1895 and 1997. From there he occasionally travelled to study open air painting in Schleißheim, in the Bavarian Alps, Kufstein and Rattenberg in the Tyrol. Here he changed his painting style once again. In his early years he had been interested in the effects of light in painting, and now he concentrated on night-time views. By contrast with Warsaw he now concentrated on the representative quarters of Munich, Max-Joseph-Platz and Wittelsbacher Platz (Ill. 10, 11), both of which were situated not far from the Munich Residenz to the west and south of the Hofgarten; and the pylons and statues lining the Ludwigsbrücke (engl. Ludwigs Bridge), over the Isar (Ill. 17) that had been modernised in 1890/91. Now the people in his paintings tend to be rather elegant even when everyday motifs like a cart full of men with dogs also occur. His painting style is naturalistic and he attempts to catch light effects by using fine particles of colour as faithful to nature as possible. Thus Gierymski followed the contemporary upper middle-class tastes of the period both stylistically and in his motifs, when we think, say, of the simultaneous Berlin night-time views by Lesser Ury (Unter den Linden after the Rain, 1888) or the highly popular “Moonshine” paintings of the time.

The fact that the new Munich paintings corresponded to aristocratic tastes is also shown by the commission he was given by the Lithuanian Baron Ignacy Korwin-Milewski (1846-1926) to paint similar motifs of Paris. Milewski, an art collector, political writer and traveller, had clearly taken courses in painting at the Munich Academy in 1875 where he had joined the circle of Polish artists and become an enthusiastic follower of their paintings. In order to fulfil this commission Gierymski travelled to Paris in autumn 1890. Here he completed his night-time views of the Louvre and the Paris Opera House (Ill. 13, 14), in both of which he made even stronger contrasts between light and shade.

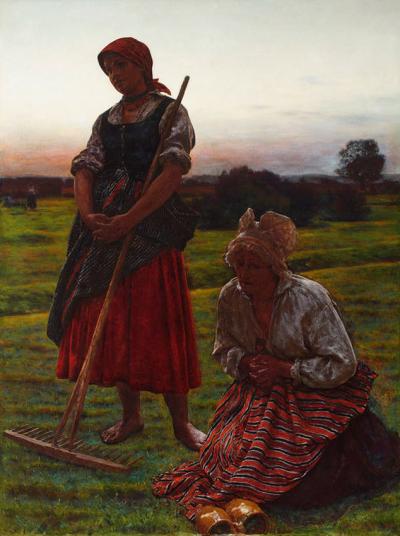

But Gierymski also used his stay in Paris in order to study French painting. He busied himself intensively with the realism of Jean-François Millet, as is shown in his version of the Angelus motif (Ill. 12), that he executed at a time when Millet’s painting L'Angelus (1859) was all the rage. In 1889 it was sold to America after heated bidding between the Parisian Sedelmeyer Gallery and the American Art Association. In 1890 the painting was resold to Paris at a huge profit to become part of the Alfred Chauchard’s collection. By contrast with Millet’s painting which shows a pair of peasants at prayer facing each other during the ringing of the evening angelus that marked the end of the working day, Gierymski shows two women at prayer, one standing and the other kneeling, in a diagonal front view that fills the picture. Millet’s pitchforks and baskets are replaced by a rake and pitchers, whereas the broad landscape and the furrows in the earth are treated in a similar fashion. But the greatest difference is in their use of colour. Whereas brown tones dominate in Millet’s painting, thereby emphasising the arduous nature of peasant’s work, Gierymski chooses bright colours that mainly reflect the clothing of the women in a folklore manner – a style that was mainly used by the Polish painters in Munich when they turned to themes related to Polish history and popular culture.

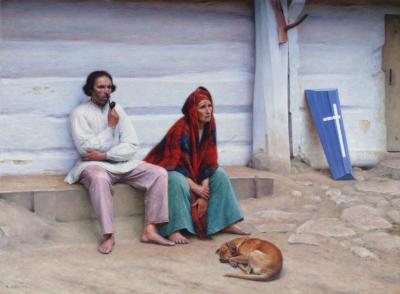

Gierymski mainly studied Impressionist painting in Paris where he changed his painting style once again. He prepared his large-scale painting Evening on the Seine (Ill. 15) by making a huge number of preliminary studies and chose the Divisionist painting style used by the Impressionists, where the colours and light reflections are divided into basic colours and complimentary contrasts in a similar manner to that used by Claude Monet in his series of pictures entitled Les Meules (engl. The Haystacks, 1888-90). Even after Gierymski returned to Poland at the end of 1893 he continued to adopt this style of painting. He moved for a while to Krakow, probably because he had been offered a leading position at the Academy of Visual Arts (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych). Here he painted impressionist pictures of sunny landscapes, streets and genre scenes, alongside portraits of the inhabitants of the Krakow suburb of Bronowice. The painting The Peasant’s Coffin (Ill. 16), also belongs to this series: it shows a peasant couple in quiet desperation in front of the coffin of their dead child with the coffin lid leaning against the side of the house. That said, the impressionist style has been smoothed out into a folklore quality.

A feeling of increasing loneliness and isolation in Polish art circles led to Gierymski setting off on his travels once again. After his years in Munich in 1895 and 1897 he was on the road, mostly in Italy (Venice, Palermo, Amalfi, Rome and Verona) and on repeated occasions in Paris once more. He changed his painting style as often as the places he stayed. He portrayed the Castle park in Schleißheim in an almost pointillist manner; by contrast he portrayed the town walls in the Corner of the Plönlein in the old town centre of Rothenburg ob der Tauber (Ill. 18) in a realistic manner flooded with light. He created views of Italian squares, church courtyards and cathedrals in a summary arrangement of bright colours and with lovingly intricate architectural details; and everyday scenes full of people as in his picture of the Cathedral at Amalfi. With his view of the Inside the Basilika San Marco in Venice (Ill. 19), he succeeded in combining an astonishing mixture of styles made up of an almost photorealistic approach, impressionist details and effective contrasts between light and shade, Aleksander Gierymski passed away at some time between the 6th and 8th March 1901 in Rome. In Polish art history he is regarded as one of the most celebrated representatives of realism and a pioneer of experiments in light and colour in Polish painting during the second half of the nineteenth century (Ewa Micke-Broniarek).

Axel Feuß, December 2016

Further reading :

Münchner Maler im 19. Jahrhundert = Bruckmanns Lexikon der Münchner Kunst in vier Bänden, vol. 2, Munich 1982, p. 25

Agnieszka Morawińska: Polnische Malerei von der Gotik bis zur Gegenwart, Warsaw 1984 (German edition), p. 37 f.

Ewa Micke-Broniarek (National Museum Warsaw) on www.culture.pl, 2004

H. Kubaszewska, in: Saur Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon (AKL), vol. 53, 2007

Maksymilian Gierymski. Dzieła, inspiracje, recepcja, exhibition catalogue Nationalmuseum Krakau / Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, Krakau 2014, p. 84

Aleksander Gierymski (1850-1901), edited by Zofia Jurkowlaniec and others, Exhibition catalogue, National Museum Warsaw / Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, Warsaw 2014

Piotr O. Scholz: Zur Ausstellungspraxis polnischer Kunst im europäischen Kontext. Aleksander Gierymski (1850-1901). National Museum Warsaw 20.3.-10.8.2014, in: Kunstchronik. Monatsschrift für Kunstwissenschaft, Museumswesen und Denkmalpflege, 68. Jahrgang, Heft 5, München Mai 2015, pp. 254-260