Andrzej Nowacki. Exploring the square

Mediathek Sorted

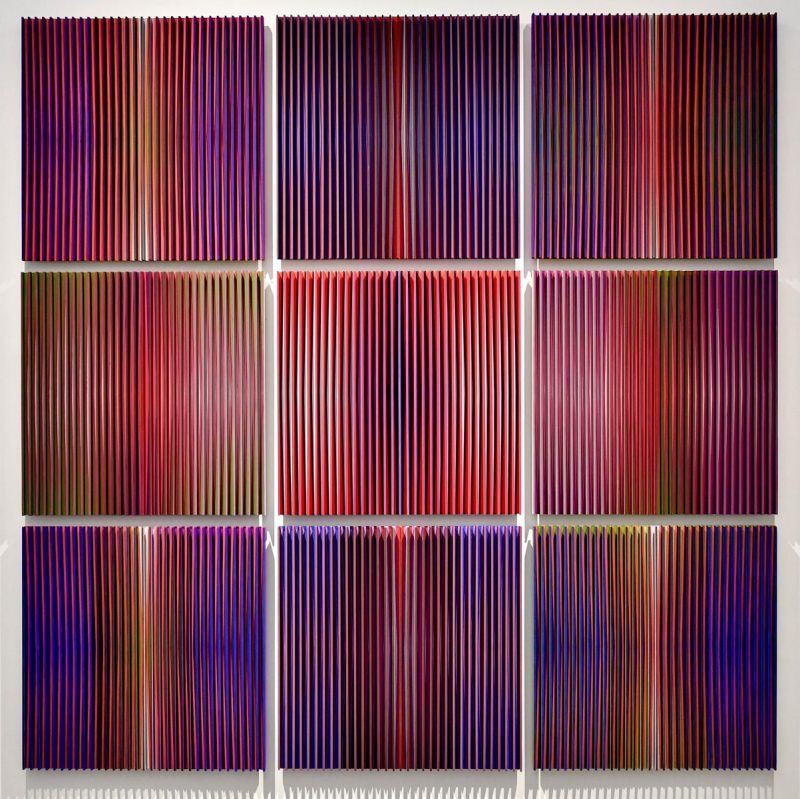

Room 3: Spar images

Slowly, the vertical lines come closer together, taking up more and more space, until finally, the base area, liberated from the earlier dynamic of colours and forms, is entirely consumed by the vertical straight lines. Shown through higher and lower wooden spars and the intervals between them, their colours alone create a radiant aura. The number of colours is limited; they are repeated in specific rhythms determined by the artist. Without being limited by any frame, not even by a background, the relief surface itself becomes the picture. There is also no axis of symmetry, even if this absence is only temporary. (Figs. 12, 13, 13a, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19)

Naturally, these images are reminiscent of a specific creative period of the British painter Bridget Riley, and the artist openly states that she was a source of inspiration. During the first decade of the new millennium, however, he clearly demonstrated his own development and his individual path. In the words of Hubertus Gaßner: “The spar images being produced during this period have liberated themselves entirely from the compositional principles of geometric abstraction, as was represented by the Polish artists Strzemiński and Stażewski, for example. They cross over into the rich tradition of striped images and reliefs, which have been created since the 1950s by Raphael Soto, François Morellet and Bridget Riley, Agnes Martin, Frank Stella and Jean Scully and others. In common with the spar images by these artists, the most recent reliefs by Nowacki have limited the composition to the most simple elements and forms in order to enhance the colours. Colour as the means of expressing feelings and emotions now has the upper hand over the previously complex, dominant compositions consisting of squares and lines.”[5]

The colours in Nowacki’s squares are wayward, moody, at times truculent. As the great master of colour compositions Josef Albers once said: “As with humans, colour behaves in two different ways: first self-realisation, then the creation of relationships to others.” If they participate in interplay, they live in contrasts and harmonies, in dispute and agreement. They lose their independence, become enmeshed into the coloured line structure. As the artist himself says: “The core value of my artistic works is colour. It supplements, indeed replaces, light. In dialogue with the observer, it forms the words of an unconscious language and becomes a source of energy.”

One key feature of these reliefs is their sensual, tangible, spatial quality, which is created through the wooden structure. First, the empty space of the square fibreboard is overlaid with wooden spars, creating a structure. The raw wood is light and warm, and is still imbued with the scent and memory of the living tree. Everything therefore begins with the engagement with the material, which must be tamed in such a way that it becomes a sensitive support for art. At times, a new dynamic is introduced to the parallel striped field of the relief: the wooden spars run in curves or are broken in a zigzag rhythm; on multiple levels, they suggest hidden geometric forms. From the start, the structure influences the future dialogue between the colours and co-creates the imaginary recessed spatiality.

An intimation of the form is revealed in the complex structure, like a cipher in the language of the linear wooden spars. Without colours, the rhythms still sound wooden, the contours of the figures remain vague and blurred; the horizontal courses of the spars become lost in the vertical order. It is through the colours alone that all the functions of slants, of diagonal lines, of higher and lower wooden spars and all their specific or perceived purposes in the image as a whole become clear. The vertical arrangement is dominant, and it is not yet clear whether it stands for the state of being grounded or whether it conversely promises the ability to overcome gravity. Perhaps the answer is both.

Not least for this reason, this first stage in the creation of a relief is of fundamental importance, even if the actions that relate to it are more reminiscent of handicraft than of art. Yet it is precisely the earth-bound, sensual result of this preliminary work that will characterise the quality of the future image for ever. This handicraft cannot therefore be excluded from the creative process; quite the opposite: already from the start, it is constitutive of the unique nature of Nowacki’s relief images and clearly sets them apart from the works of other artists in this genre.

[5] Ibid., p. 12.