Tales from the hills. The fate of Polish forced labourers at Porta Westfalica 1944/45

Mediathek Sorted

“The work continued day and night without interruption”[26] – the working conditions of the forced labourers

Multiple armament production sites and underground relocations were planned for the area around Porta Westfalica. In the “Dachs I” underground site, in the lower system of mining tunnels in the Jakobsberg hill, a lubricant oil refinery for the Hanover-based company Deurag-Neurag was planned, with the production area of around 6,500 m².[27] Meanwhile, the “Stöhr I” underground site in the upper tunnel system of the Jakobsberg was selected as the site for a tube production facility for Philips from Eindhoven in the Netherlands, the Philips subsidiary Valvo from Horneburg and Telefunken from Berlin, as well as for the production of wire coils for Rentrop from Stadthagen. The facility overall was to extend over several storeys and cover an area of around 9,000 m².[28] On the opposite side of the Weser, in the Wiehengebirge hills, in the “Stöhr II” underground site, also known as the “monument tunnel”, a four-storey site covering a total area of 5,320 m² was planned for the production of ball bearings for fighter planes for the company Dr. Ing. Böhme GmbH & Co. KG from Minden, as well as the production of parts for tank defence weapons for the Veltrup KG company.[29] The armament production complex at the Porta also included the local concrete production company, Betonwerk Weber in Lerbeck, which initially received an order from the SS in March 1944 for the production and delivery of concrete panels and supports for the construction of the concrete halls in the mining tunnels. In September 1944, the factory complex belonging to Betonwerk Weber was seized and made available for armaments producer Klöckner Flugmotorenbau GmbH for repair works for the Luftwaffe. The company was moved to the Porta from the Netherlands due to the critical situation at the front.[30]

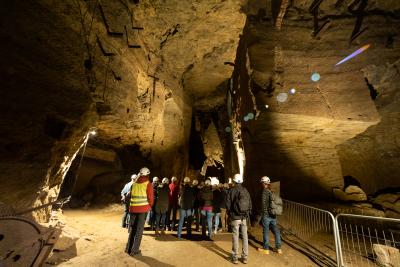

The forced underground labour occurred in two phases. During the first phase, from March 1944, concentration camp prisoners were mainly used to extend the mining tunnels for the production relocation in the Jakobsberg and Wiehengebirge hills to enable the armament production sites to be set up there in the first place. Only then did it become possible to move the production complex that was necessary for the war into the extended tunnels, and in some cases to begin production even before the end of the war.[31]

Wiesław Kielar recalled the following in relation to the people who made up the labour force and their place of origin: “The work continued day and night, without interruption. There were people of all nationalities here – those who were subjugated and those who were from the Axis powers”.[32]

The wide range of tasks involved in construction the armament production sites in the area around the Weser river demanded a huge amount of labour, which was provided by various groups of forced labourers[33] as well as by civilian workers – including from the German population. However, there were fundamental differences in the way in which foreign forced labourers and German labourers were regarded, and in terms of the tasks they were made to perform and the way they were treated. Concentration camp inmates, prisoners of war, and also civilian workers who had been brought from abroad, were made to perform particularly physically demanding tasks, and in many cases suffered from inhumane working and living conditions. In the main, for example, workers from the concentration camps were made to toil on the expansion of the tunnel systems.

[26] Kielar, Wiesław, p. 375.

[27] See Blanke-Bohne, Reinhold: Die unterirdische Verlagerung von Rüstungsbetrieben und die Außenlager des KZ Neuengamme in Porta-Westfalica bei Minden, pp. 37

[28] See ibid., p. 37, pp. 46

[29] See ibid., p. 50 f.

[30] See ibid., pp. 67; see Schulte, Jan Erik, p. 141.

[31] See Blanke-Bohne, Reinhold, p. 50.

[32] Kielar, Wiesław, p. 375.

[33] They included male and female concentration camp inmates, prisoners of war and civilian labourers who were brought specifically to work at the Porta. In some cases, the companies producing in the underground facilities also brought their own workers to the Porta. Some of them came voluntarily, while others were forced to work against their will.