Stefan Szczygieł. His photographic and film work

Mediathek Sorted

![“Feuerzeug” [Cigarette lighter] “Feuerzeug” [Cigarette lighter] - From the series “Blow Ups”, photogram, 200 x 300 cm.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/07_feuerzeug.jpg?itok=lVUakM66)

![“Telefon” [Telephone] “Telefon” [Telephone] - From the series “Blow Ups”, photogram, 200 x 260 cm](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/09_telefon.jpg?itok=McBWeT4z)

![“Taschenuhr” [Pocket watch] “Taschenuhr” [Pocket watch] - From the series “Blow Ups”, photogram, 250 x 200 cm.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/10_taschenuhr.jpg?itok=yuY8kMzC)

![“Warsaw, Bridge” [Warschau, Brücke] “Warsaw, Bridge” [Warschau, Brücke] - From the series “Urban Spaces”, 2005-2009, Inkjet photo print, 60 x 170 cm (Edition: 10).](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12_warschau_bruecke.jpg?itok=_mrZqMgU)

ZEITFLUG - Hamburg

ZEITFLUG - Warsaw

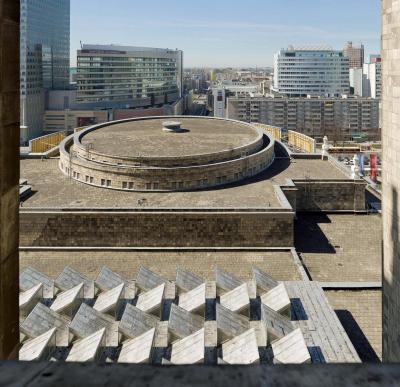

Urban Panoramas

Finally Urban Spaces led to a subgroup: to huge photos designated by Szczygieł as Urban Panoramas, and presented in outside spaces, often near or exactly on the place where the photos were taken.

His overall concept foresaw changing the photographs of urban scenes at regular intervals. He would start by installing a photo of a local place in the place itself, but after a few weeks this would be replaced by a new photograph from another city in the same format and in a weather resistant manner. In this way there was not only a past image of the place itself but also of a place in another city in another country – a city within the city. The over-dimensional photographs, initially a confrontation between chronological, spatial and urban links with his own city, were later given another counterpart. Comparable to the Blow Ups, Szczygieł was also provoking us to reconsider the given situation and question the interrelation between perception and usage. The Urban Panoramas are an even more brazen confrontation when another city is brought into play. Thanks to their gigantic size the panorama photos are an adequate counterweight to the passers-by in the city and cannot be interpreted as models or miniature representations.

In this way Szczygieł constructs a learnt identification: 17th century European landscape painting and landscapes in 20th century Cinemascope films recalled these and other iconographic associations and this led to viewers projecting themselves into the landscape. According to their perspective and size they place themselves within the “landscape”, or to put it more precisely, enter the urban landscape, thereby identifying themselves with the city per se and with all the imagery in the photograph. The only difference is that the viewers are not moving through the photo on foot or with a vehicle, but with their eyes. Nonetheless it was extremely important for Stefan Szczygieł to point out – and this functioned particularly accurately with the selection of the photographic excerpts and the exchange of photos from another city like Paris, for example – that landscape painting and artistic photography, as well as documentary photos of urban spaces should be interpreted as revelations of manipulations. In his view the geometry of a city was always a manipulation. This was not only true of the use of the formal language of nature: from a quarry, via Jugendstil to the present day when next-door buildings, parks, the sky and the clouds are reflected in glass palaces and try to fool us that material simulation is the same as the natural product. For him, this is all about manipulating communication. Szczygieł’s work leads viewers to ask questions like: what is the highest building, who built it, in what direction are the streets running and what buildings stand there, at what point do the bridges cross the river and which monuments are dedicated to what or to whom? How long and wide must a street, an avenue or a boulevard be, what were their original functions and which of them have changed in the course of centuries? What is the meaning behind the individualisation of architectural styles and monolithic detached buildings? What effect do huge commercial images have on the city and the people living in it, and what effect does urban illumination have on light pollution?