Poles in Breslau (until 1939)

Mediathek Sorted

Sellers, craftsmen, domestic employees

In the 19th century, Poles began to arrive in Wrocław from the overpopulated regions of Wielkopolska and Upper Silesia. At first, they took on various types of casual work as long as they were earning their keep. They worked in industry, craft trades and services.

“Service in inns and shoppers in stores – wrote Wincenty Pol in his travel diary of 1847 – at first glance and everywhere there will be at least one person in a local or commercial store who speaks good Polish. All inscriptions on shops were written in two languages. Even the Germans, the owners of estates, whose goods are near to where the locals speak Polish, are learning the language to meet the needs of the people”. (Pol, Dzieła ..., p. 179).

Some of the rules set out by the city authority, such as firefighting, were also published in the Polish and German language.

“But”, as Teresa Kulak, an expert in the history of Silesia, commented “the overall image of the town was dominated by the German language and culture to which to the Jewish population adapted more and more”. (Kulak, Historia Wrocławia…, p. 47).

Many representatives of the Polish intelligentsia, mainly doctors, solicitors and members of land owner’s families from Wielkopolska and Pomerania, also lived in Wrocław.

Over time, the Poles also made their presence felt among the ranks of the wealthy bourgeoisie. The Poles opened businesses, workshops, hotels, pharmacies and chemists, some even had small factories. It is estimated that around 20,000 Poles were living in Wrocław at the turn of the 20th century (the official German statistics gave the number as 7,000-8,000 people).

Polish community life was played out in various rented halls. National holidays were organised and important personalities from Polish history and culture were remembered. Charity events (such as presents for poor children before Christmas) attracted a lot of attention. Popular dance evenings were held in Vinzenzhaus (today Frycza Modrzewskiego street). Even the German population got involved.

Nucleus of the Polish intelligentsia

The Friedrich Wilhelm University in Silesia played an important role in the process of creating a Polish intelligentsia. It was founded in 1811 and, for several generations, attracted young Poles from Wielkopolska, Upper Silesia and Pomerania (at some point they even accounted for a third of all matriculated students). Wrocław University was closer to their family homes that the one in the capital Berlin. They began their studies with the aim of gaining a diploma that would offer them the chance of a career in administration, in education or in the liberal professions (they counted the most bourgeois and representatives of the lower nobility amongst their number). This is reflected in the areas of study they chose: medicine, law and economics were very popular, followed by philology and theology.

From the outset, Polish students, just like other students, established various organisations. 1818 saw the founding of the “Polonia” organisation whose members made it their goal to fight for an independent Poland, true to the motto “Freedom and Fatherland”. The youths later took part in the November Uprising of 1830/31, without any form of repression. Polish students could also be found in the rebellion parties of 1863. Adam Asnyk, Jan Kasprowicz and Wojciech Korfanty were just some of the students at the university at the end of the 19th century.

Other organisations that brought together young people of Polish heritage were founded at Wrocław University in the first half of the 19th century. The Literary and Slavic Society was founded in 1836. The Czech philologist and anatomist Johannes Evangelist Purkine (1787-1869) was elected President. Membership required an interest in Polish history and culture and the preparation of talks. These talks formed the basis for discussion within the forum of the society.

The Chair for Slavic Language and Literature was established in Wrocław in 1841 as a result of the liberal policies of King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Polish language courses have been taught at the University since 1812. The royal decree declared that it had been established to

"give young people of Polish heritage studying at the local university the opportunity to improve their abilities in their mother tongue" (cited from Teresa Kulak, Historia Wrocławia ..., p. 188).

In the 1860s, Wojciech Cybulski, who had taken part in the November Uprising (his successor, Władysław Nehring, headed up the courses on Polish Literature until 1907), held the chair.

Polish students from various partitioned territories were also active and founded their own organisations in the second half of the 19th century. In 1863, students from Upper Silesia founded the Association of Polish Upper Silesians. Its aim was to improve the knowledge of the Polish language, history and culture. In 1868, students from Wielkopolska and Pomerania founded the Circle or Wrocław Academics of Polish Nationality.

The period of anti-Polish German policies in the second half of the 1880s also had an impact on the Polish organisations. Despite all the prohibitions, Polish organisations were reborn. In the end, after yet another anti-Polish decree, it was decided to establish secret organisations.

The city of migrants

In the 19th century, the paths of Polish migrants crossed from East to West via Wrocław. Amongst the migrants were people who had been involved in national uprisings and members of other conspiracy organisations directed against the partitioning powers. Demonstrations were organised and held in Wrocław and arms transfers were prepared. Many of these Poles stayed in the city for longer periods.

During the Spring of Nations, the Poles in Wrocław supported the democratic forces and the Polish flag hung on the university building at the time. In May 1848, a large Polish political congress was held in Wrocław in which Poles from the three partitioned territories participated. Wrocław was selected to host the event because of its good rail connection and emergency precautions were taken by the police. Around 300 “born revolutionaries” were driven out of the city and deported to neighbouring Saxony. In the years that followed, the police continued to monitor the Polish environment.

The German inhabitants of Wrocław did not always welcome the Polish political activities. They were increasingly perceived as a threat to German unity, the state and the nation. This negative attitude had already been demonstrated during the uprising in Wielkopolska in 1848. At the beginning of the 1860s, demonstrations were held again and, during the January Uprising of 1863, Wrocław once again became a central figure in the conspiracy. Polish craftsmen and students from Wrocław took part in the uprising, which was also reported on by the Wrocław media. A representative of the insurgent national government remained in the city.

Polish travellers and tourists

Many representative of the Polish intelligentsia were represented in the metropolis on the banks of the Oder. They were motivated by contact with Korn publishing house (it offered over 180 Polish literature titles). Korn published their own books and bought new publications. The Ferdinand Hirt bookshop specialised in the sale of Polish books. It is estimated that Wrocław was the sixth biggest Polish publishing town behind Warsaw, Vilnius, Kraków, Lviv and Poznań. In total, 2,000 titles were published in the city in the 19th century.

Polish landowners came to Wrocław from Wielkopolska and Pomerania to attend trade fairs. They stayed in hotels and visited restaurants in the city. The theatre, the opera and concerts drew a great deal of attention. Polish artists from Poznań or Kraków performed on the stages of Wrocław. In 1830, Fryderyk Chopin, who was enjoying a short stay in Wrocław, gave a piano concert for a select audience.

Just how important Polish guests were to hoteliers and restaurateurs can be evidenced by the fact that adverts for their services were also printed in the Warsaw press. One of the owners of the famous guest house “Unter der Goldenen Gans”, whose guests also included Fryderyk Chopin, informed their visitors:

“Polish and French are spoken in this hotel and we offer newspapers in these languages”.

Restaurants went to the effort of putting on Polish menus and even the wait staff spoke Polish. Access to the restaurant was encouraged by signs in the Polish language. Such a proliferation of the Polish language was neither surprising not did it meet with opposition. The personalities from Polish culture in Wrocław included Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Wincenty Pol, Klementyna Tańska Hoffmanowa and Józef Ignacy Kraszewski.

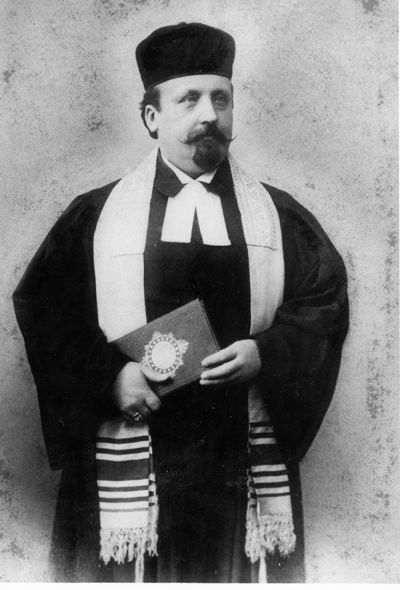

Spiritual life in the 19th century

Taking part in church services was not just of a strictly religious dimension, it was an important manifestation of spiritual life. Poles were already taking part in church services in Polish around the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. They were organised on a regular basis for the worshippers of the Evangelical and Catholic churches. Evangelical services were held in the church of St. Christopher, whilst catholic services were held in the churches of St. Kreuz and St. Adalbert.

“(….) The German and Polish languages”, wrote Hugo Kołłątaj at the beginning of the 19th century, “are so familiar to the residents that church services for all religions are even held in both languages”.

After 1820, an order passed by church authorities restricted services in Polish in churches belonging to both confessions. This was an extremely serious turn of events. As there were no Polish organisations at the time, using the Polish language in religious practice offered the only possibility to maintain the language. This new situation meant that Polish was soon no longer on an equal footing with German.

“Wrocław’s residents”, wrote Friedrich Nösselt, the author of a city guide from 1825, “are predominantly of German heritage. There are only a few Poles and so it is not easy to hear any language other than German being spoken. Many may perhaps be of Slavic origin but the residents have intermixed for so long now that it is not possible to differentiate between those who are of Old German origin and those who are Slavs”. (F. Nösselt, Breslau ..., Breslau 1825, p. 225).

In the middle of the 19th century, sermons and songs in Polish could only be heard in the collegiate church of the Holy Cross.

The development of organisational life

In the second half of the 19th century, the Poles’ social activity in Wrocław increased. Different types of organisation were established. The Association of Polish Industrialists was founded in 1868. Its members were craftsmen, merchants and other people associated with providing services. As well as aiming to achieve a better exchange of information between industry representatives, national challenges were also faced. Lectures and academies were organised. The association had 70 members and formed its own welfare fund.

“The Association of Polish Industrialists in Wrocław is a real blessing for our fellow countrymen", wrote the popular Beuthen newspaper ‘Der Katholik’ in 1881. “The society has a beautiful reading room, holds pedagogical talks, Polish theatre performances and others.”

Ludwik Adamczewski (1863-1952), a tailor from Poznań, came to the city as president..

A choral society called “Harmonia” and a fund for mutual aid were set up in the city. The Polish Catholic Society (1890), the “Lutnia" choral society, the Trading Company and the St. Anna Women’s Association were founded at the end of the 19th century. The latter was established by Aurelia Żychlińska, Jadwiga Kamińska and Jadwiga Jarochowska. They organised social gatherings and talks as well as Polish courses. J. Kaminska also founded the Society of Popular Readers. It had a library containing around 6,000 volumes.

The gymnastics club “Sokół” was established in 1894 and the Volksbank in 1904.

Many events were held in the restaurant at Neue Gasse / Nowa 18; the nearby restaurant “Eldorado and Casino” was also used. The owner of the former was Jan Kwaczewski, also a Pole.

The interwar period

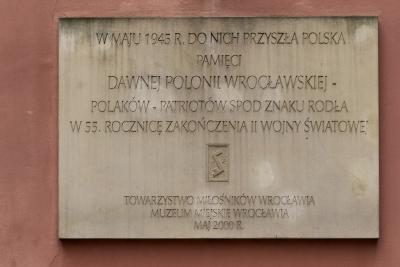

The situation for Poles in Wrocław changed after the end of the First World War thanks to the restoration of the Polish state and the resolutions of the Treaty of Versailles. The entry into force of the Treaty led to the founding of the Consulate of the Republic of Poland on 22 May 1920 (the first consulate was housed in an apartment building at Neue Gasse / Nowa 18, then in the house at Am Ohlauufer 2, today Słowackiego Street. This house is no longer standing.) The first consul was Eustachy Lorenowich. The status of ‘Polonia’, or Polish diaspora, was endowed upon the Polish citizens of Wrocław. Their rights, just like those of the entire Polish minority, were guaranteed in the German state by the constitution of the Weimar Republic.

The lack of acceptance of the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, particularly those concerning the German-Polish border, led to conflicts between Poles and Germans. The Poles began to organise support for the people’s referendum in Upper Silesia. However, the meeting to appoint the plebiscite committee was broken up and its participants were beaten by the German militia.

Other incidents were also associated with the referendum. On 26 August 1920, following the demonstration against the referendum, which was held on the Schlossplatz, German demonstrators went to Neue Gasse / Nowa 18 (as well as the Polish Consulate, the “Polish school” and the library had also been located there since May of that year). They then entered the premises and destroyed them. Windows were broken, furniture destroyed, books thrown out of the window onto the street (a similar fate befell the French Consulate, which was held responsible for the provisions in the Treaty of Versailles that were unfavourable for Germany). The perpetrators were given mild sentences. The Republic of Poland demanded damages which it was not paid until several years later.

The year 1922 and the partitioning of Silesia were an important milestone in the history of Poles in Wrocław. Thousands of people left the city, including the most influential group of Polish intelligentsia. Only craftsmen and smaller merchants remained. It is estimated that there were still around 3,000 Poles in the city at this time.

Despite the hostility of some of the German residents and the fact that a large number of Poles were leaving the city, the remaining Poles tried to continue organisational life and ensure that the poor and needy were supported.

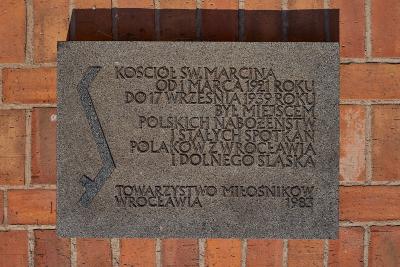

The meetings continued to be held during church services and on the premises of various organisations. In 1919, the church of St. Anna in St. Jadwiga Street, which replaced the church of St. Martin on the Dominsel in 1921 (the last service for the Polish congregation was held there on 17 September 1939), was tasked by the German church authorities with reading Polish mass. The first priest of the Polish congregation was Father Józef Matuszek.

On 14 January 1923, a branch of the Union of Poles in Germany, the leading Polish organisation, was founded in Wrocław. Franciszek Juszczak, a tailor by profession, became its president (he held this position for the whole of the period between the two wars). In 1924, a new student organisation, the Association of Academics from Upper Silesia, was established to bring young people from Upper Silesia together.

Polish community life was organised in the “Polish House” at Henryka Pobożnego Street 21/23, which met weekly. National holidays and anniversaries were organised and Polish students played an active role in the work involved. Amongst other things, they founded a choir, gave Polish courses, and organised theatre and scout activities.

After the assumption of power by the National Socialists in 1933 in conjunction with a change in the political relations between Poland and Germany, the Wrocław Polonia was given full rights of disposal over the building in Neue Gasse, which had been acquired in 1922. A student hall of residence was opened there. The editorial offices of both the magazines published by the Union of Poles in Germany “Mały Polak w Niemczech” and “Młody Polak w Niemczech” also found their new home there. in March 1938, delegates from Wrocław took part in the Congress of Poles in Germany, a large-scale meeting of the Polish minority, but a few months later the German authorities made political demands of Warsaw that were unacceptable for Poland. Berlin had returned to a policy of discriminating against Poles in Germany. The building in Henryka Pobożnego Street was taken away from them. Polish organisations bought the building at Schweidnitzer Stadtgraben 16a (Podwale). All Polish organisations, such as the kindergarten and the library, found their new home there.

The German authorities’ anti-Polish policy intensified in the months before the outbreak of the Second World War. More and more restrictions were placed on the potential to carry out organisational activities and repressions were initiated. The Poles were even asked to change their Polish-sounding names to German ones. In June 1939, Polish students were prohibited from entering the university buildings and police searches were carried out in the Polish house in Podwale. Several books were confiscated. Police officers photographed worshippers leaving mass at the church of St. Martin. On 13 September after the outbreak of the Second World War, Polish activists were arrested and deported to a concentration camp. All Polish organisations were dissolved and their assets taken by the German state.

Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, June 2018

References:

Friedrich Nösselt, Breslau und dessen Umgebungen, Breslau 1825; Wincenty Pol, Dzieła wierszem i prozą, Vol. 10, Lwów 1878; Teresa Kulak, Historia Wrocławia. Od twierdzy fryderycjańskiej do twierdzy hitlerowskiej, Vol. 2, Wrocław 2001.