Poland’s path to freedom on SPIEGEL covers 1980 to 1990

Mediathek Sorted

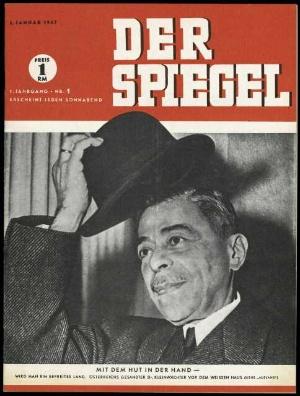

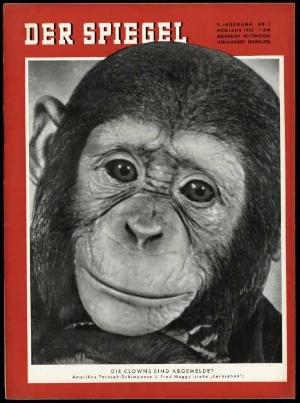

The first issue of the magazine appeared at the beginning of January 1947 and had only 28 pages. From the outset, the SPIEGEL[2] was created as an illustrated magazine and the influence of the weekly American news magazine “Time” and the British magazine “News Review” cannot be denied. Both magazines were given as sample copies to young SPIEGEL editors by British officers who oversaw the creation process of the magazine.[3] (Fig. 1-3) The publishers had articles from “Time” and “News Review” translated into German so that the editors could learn how to adapt the journalistic style that was unknown in Germany at that time. The graphic design also drew on the visual samples of the English-speaking opinion sheets. What Rudolf Augstein, the co-founder and long-time publisher, remembers about the layout is encapsulated in his laconic statement that the characteristic “eye-catching” dominant red colour of the cover is purely declaratory.[4] In actual fact, in the first few years it ranged between red and orange.

The cover of an illustrated magazine is its calling card. And this was true of the SPIEGEL too, whose cover gained almost cult status and became an integral part of the visual cultural heritage in Germany. At that time, the colourful covers of the new media in the kiosk windows, in which they vied for the attention of passers-by, became a kind of stage on which photographers and graphic designers shone. A turning point in the SPIEGEL’s ability to be recognised came in 1955 when the first issue was published with the reddy orange cover which is still a feature today and which was created by the long-standing head of the graphic design department, Eberhard Wachsmuth. (Fig. 4) The colourful frame on the cover has been a fixed element of the magazine ever since. The earlier layout from 1947 to 1954 still split the space into a red header, which took up the top third of the page, and a field underneath it with the actual cover image.

The SPIEGEL cover announced the theme of the week and illustrated it with a photograph, a photomontage or a cartoon. For every one of the 52 cover pages in a year, there were ten times as many drafts from which the editorial staff then chose the cover.[5] The cover design was also created by freelance graphic designers. Some of the most well known unquestionably included artists who, like Boris Artzybasheff, Jean Sole, Tilman Michalski, Ursula Arriens and the Pole Rafał Olbiński, had also worked for the weekly magazine “Time”.[6] Dieter Just’s research shows that cover pages with male likenesses were over represented until the middle of the 1960s. In 1956, 88 % of the cover pages showed images of men and 4 % showed women. The other covers featured inanimate scenes and objects.[7] For many years, these ratios did not really change much. But the visual design of the cover did. The proportion of photomontages or cartoons depicting scenes and personalities increased and the use of portraits declined. In all this, the covers of the SPIEGEL quickly became an institution in the German media landscape. In 1972, they were even exhibited at one of the most important art events in the world Documenta, which is held in Kassel every five years. This was not just due to their artistic value but also, in particular, to their relevance as a social iconography of everyday life which Harald Szeemann, the curator of Documenta 5, attributed to them. He selected 40 cover pages which were put together to form a series of prominent political events which, in his opinion, threw up topics of enormous importance not just to Germany society but also to world politics of the time.[8]

At a very early stage, the SPIEGEL showed its interest in topics relating to Poland by including them in its first issues even though they were still having to make do with relatively few pages. Two articles in the first issue of 4 January 1947 were already devoted to Polish themes and are mentioned here because of their slogan-like headings which were still embroiled in war rhetoric. One text appeared under the title “Lebensraum – rot lackiert” (“Habitat – painted red”), the other was entitled “Noch nicht verloren – polnische Wirtschaft hinter der Oder” (“Not yet a lost cause – Polish economy behind the Oder”). The first article refers to a word from General Władysław Anders to the Zurich newspaper “Die Tat” and states that: “Poland [today] is not in a position to digest the German territories up to the Oder [economically].”[9] The second article, which takes the same line in both its phrasing and content, highlights the fact that, because of the migration of Germans from the former Reich territories and because of its labour shortage, Poland will not be in a position to deal with these upheavals. Barely twelve months later, the SPIEGEL, as the first media organ in the British occupied zone, began to print the diaries of Stanisław Mikołajczyk, the Prime Minister of the Polish exile government who had already stepped down at that time.[10]

In the 1980s, which were plagued by enormous political crises, Polish topics also appeared more frequently and, similar to the turbulent 1940s, were represented by personalities who were critical of the political system in the country beyond the Oder in the post-war years. Straight after the war it was Stanisław Mikołajczyk and now, almost half a century later, it was members of the opposition, such as Lech Wałęsa, Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik, who were turning against the communist government. It should be noted at this juncture that a constitutive feature of the magazine, but also of other opinion-forming media, is that topics are examined in a multivoice discourse from at least two perspectives. Accordingly, the SPIEGEL reported about events in Poland from the perspective of the widely understood opposition and from the perspective of the ruling powers, as is shown by the presence in the magazine of the people mentioned above, but also of Mieczysław F. Rakowski and other important representatives of the Polish United Workers’ party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza).

The texts about Poland from the 1980s contain a typical historical philosophical narrative which chooses to use the words “Polish drama” to represent the complicated history of the country. According to Stanisław Mikołajczyk writing in his diaries, “Poland, which is first conquered by Adolf Hitler and later left in the lurch by its allies, might seem to the readers like a faraway land. (…) and its tragedy may perhaps be touted by some as the normal state of Europeans and particularly of Poles. But what happens in Poland today also affects them [the German readers – author’s comment].” – This passage is quoted again by the magazine’s editors in the second issue in January 1982, this time in connection with the quotation from the American author William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”[11] – This passage is quoted again by the magazine’s editors in the second issue in January 1982, this time in connection with the quotation from the American author William Faulkner: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”[12] At the beginning of the 1980s, as the SPIEGEL writes, the “Polish drama” returns and overshadows the past which resulted from the Yalta Conference.[13]

In the last few weeks of the 1980s, a series of five extensive articles were published offering a detailed introduction to the Polish issue. To some extent, the articles constitute an historical philosophical filter through which the editors saw the situation in Poland at that time. From today’s perspective, the series of articles, which was published in five consecutive issues under the general heading “Wie Polen verraten wurde” (“How Poland was betrayed”)[14], seems to be an almost prophetic anticipation of the explosiveness of the change processes which started with the events in Gdańsk in August 1980. The magazine offered a comprehensive analysis of the Polish political system in the recent history of the country, from regaining its independence in 1918 to the invasion by Hitler in 1939 right up to the restructuring which evolved during the meetings of the “Big Three” [victorious allies – Translator’s comment]. Apart from this reconstruction of the history of the Polish state after the First World War up to the outbreak of the Second World War, the articles also offer an equally apt geopolitical summary in which the tragic fate of the Polish state emerges as a consequence of the conflicting interests of the superpowers. The meta level of the historical process and of the geopolitical conditions, which are made accessible to the reader in this series of articles, set the interpretative framework for the current, almost weekly reporting from Poland. The causes and consequence of the events of the time could no longer be reduced to internal crises in society, in the party machine or in the political opposition, instead it was caught up in a greater superstructure of political interdependences of the superpowers. But the editors’ interest in Polish issues was also a consequence of the magazine’s structure. The SPIEGEL did not have any permanent columns that dealt with Poland. This meant that the frequency of reporting took its cue from the relevance of sociopolitical events. Naturally, the inclusion of Polish issues was also dependent on the competition for good news so that in times of tension and unrest there was a lot to be read about Poland and less when nothing out of the ordinary was happening. This trend applied to both editorial considerations and the cover pages.

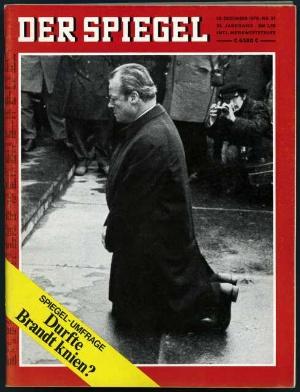

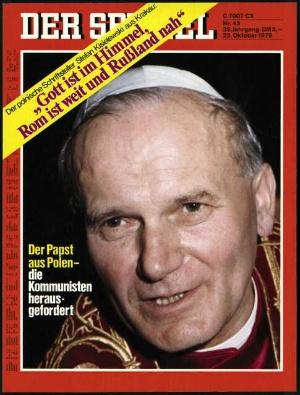

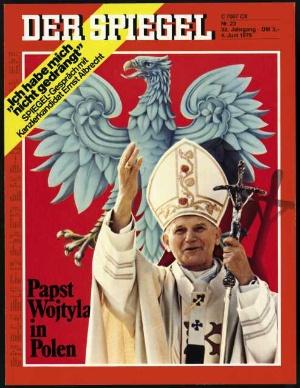

Against this background, a search for articles and covers dealing directly and only with Polish issues in the twenty years since the magazine was founded is futile. In the collective memory of the Germans, one cover in particular lives on – that of the Chancellor of the Federal Republic symbolically on bended knee. The black and white photograph of Willy Brandt’s grand gesture in Warsaw in 1970 is one of the most printed press photographs of all time and to this day is one of the most well known images of the German Chancellor. (Fig. 5) The SPIEGEL also acknowledged the election of a Pole to the office of Pope on their cover. The portrait of Karol Wojtyła on the cover of the 43/1978 issue introduced the cardinal to German readers directly after his election as the head of the Catholic Church. The heading chosen at the time: “Der Papst aus Polen – die Kommunisten herausgefordert” (“The Pope from Poland – communists challenged”) left readers in no doubt that the magazine’s editors recognised the political significance of the conclave’s outcome for Poland and the whole of the Eastern Bloc. (Fig. 6) Several covers were devoted to the Polish Pope. Another opportunity presented itself on the occasion of John Paul II’s pilgrimage to Poland from 2 to 10 June 1979. This was the first time in the history of the Holy See that its guardian had entered a communist country. The Hamburg magazine did not miss the symbolic religious aspect and the political dimension of the visit and this was reflected on the cover of issue 23/1979 of 4 June. (Fig. 7)

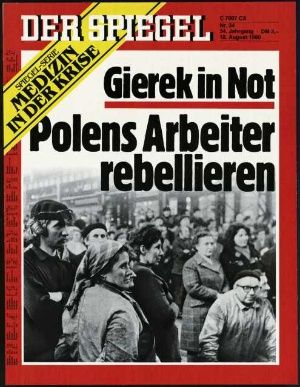

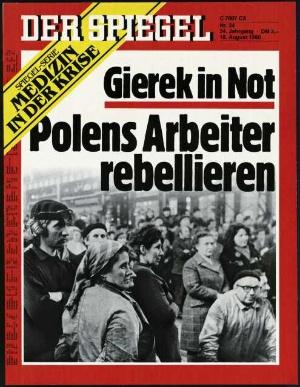

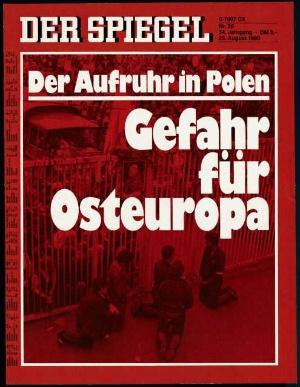

At the beginning of the 1980s, the interest in Polish issues grew. Between 1980 and 1990, the magazine devoted almost thirteen covers to the sociopolitical situation in Poland or to Polish personalities. In 1980 alone, the SPIEGEL referred to Polish issues on its covers around five times. The events on the Polish coast in August 1980 meant that the Western press and the Western media started to direct their attention to the striking workers in the state-owned enterprises in the north of the country, in particular at the Lenin shipyard in Danzig (Stocznia im. Lenina w Gdańsku). The cover story in the 34/1980 issue was a rapid reaction of the magazine to the striking Danzig shipyard workers and to the social crisis in Poland, which was intensifying from day to day. The cover image showed a section of a photo of the shipyard workers at a demonstration. Above the image was printed in bold lettering the proclamation of the issue’s cover story: “Gierek in Not – Polens Arbeiter rebellieren“ (Gierik in crisis – Poland’s worker’s rebel”) with “Gierek in crisis” being underlined in red to stand out even more. (Fig. 8)

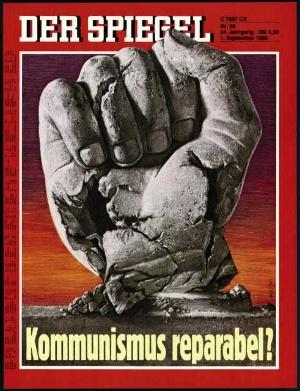

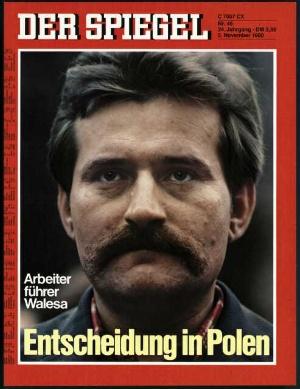

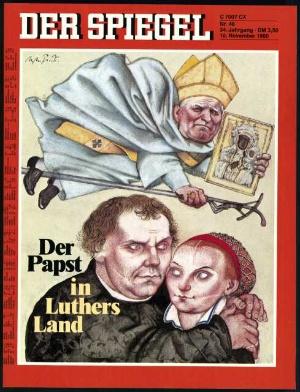

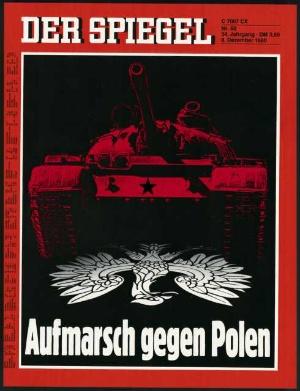

A week later, on 25 August 1980, the next issue was published and that cover was also devoted to an event in Poland. The cover of issue 35/1980 was created using a touched-up photo that had been taken in front of the gate to the shipyard in Danzig and which showed workers praying before an image of John Paul II hung on the gateway. (Fig. 9) The touch-up of the black and white photo involved it being coloured blood red so that in a chromatically consistent composition it blended into the whole cover page on which the cover story was announced in bold white letters “Der Aufruhr in Polen – Gefahr für Osteuropa” (“Unrest in Poland – Danger for Eastern Europe”). The first part of the title, “Unrest in Poland”, was also underlined in white. At the same time, the red colouring of the cover clearly depicted just what danger was being hypothesised: Red is the symbol of blood that could flow down on to the workers at prayer. The next issue, number 36/1980, was also dedicated to the crisis in Poland and its cover also took up the Polish issue, although the visual reference to the situation in the country was not as clear as in the two previous printed covers. (Fig. 10) It shows a stylised crumbling fist made of stone. At the time, the caption worded as a leading question read “Kommunismus reparabel?” (“Communism repairable?”)[15]. This cover was created by Ursula Arriens, a very successful artist, who created covers exclusively for the SPIEGEL from 1978 to 1988. With this motif, its creator concisely addressed the progressive erosion of the communist ideology, which was accelerated significantly by the emergence of the trade union movement Solidarność (Solidarity) as a new force. The next cover to feature Poland was the 45/1980 issue of 3 November. (Fig . 11) It was adorned by a colour portrait of Lech Wałęsa, which was given the caption “Arbeiterführer Walesa” (“Workers’ leader”). Under this, in a much larger font, was the title of the cover story “Entscheidung in Polen” (“Decision in Poland”). This issue was published the day before the legalisation of the trade union movement. Shortly afterwards, on 10 November 1980, the government agreed to the registration of the Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy „Solidarność” (Independent Self-governing Trade Union Confederation “Solidarity”). In doing so, the legal activity of the new organisation began. The cover of the next issue of the magazine did not reveal any direct connection to the political unrest in Poland but it did show the Polish Pope John Paul II almost as a caricature hovering symbolically above the head of Martin Luther. The drawing was created by the German graphic artist and painter Michael M. Prechtl. With this image, the cover addressed the issue of the Pope’s apostolic journey to Germany. (Fig. 12) At the end of 1980, yet another issue of the SPIEGEL appeared with Poland on its cover; the last of five covers within one year that were dedicated to Poland. That period in which Solidarność was operating legally, which is occasionally referred to as the “The Solidarity Carnival”, stirred up hope in the Polish community that at least the monopoly of the State party as the sole representative of society would be broken. From the Federal Republic’s perspective, there was a real fear that the social and political unrest could escalate so badly that there could be an armed intervention by the USSR in Poland. This is the context in which the cover of the 50/1980 issue, which arrived in kiosks on 8 December, is to be understood. (Fig. 13) The black and red colouring showing a Russian tank rolling over a white eagle, the central element of the national emblem of Poland, creates a menacing tension and is designed to make the reader concerned. With this in mind, the cover is worded as a warning. It says “Aufmarsch gegen Polen” (“Deployment against Poland”).

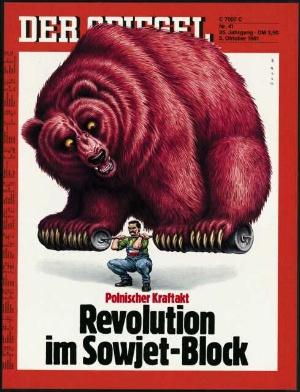

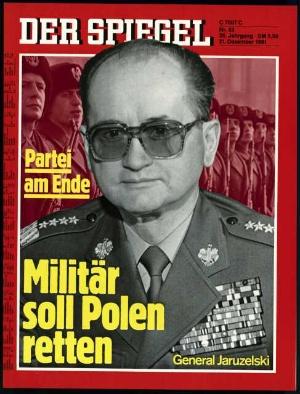

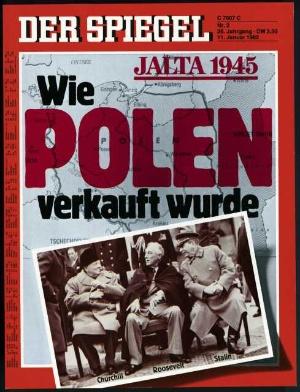

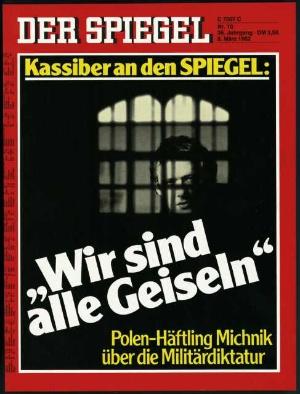

A few weeks before the proclamation of the state of emergency in Poland, also known colloquially as martial law, the Polish issue was back on the cover of the magazine. The October issue 41/1981 appeared with a cover which received a lot of attention at the time because it showed the very curious scene of a crouching Lech Wałęsa as a weight lifter. (Fig. 14) An enormous red bear is sitting on the already heavy weight that the leader of the Polish worker movement has to lift. The symbolism captured by the artist clearly makes one think of the “Russian predator” that the power athlete is wrestling. The weight, the size of the predator and its angry countenance create a threatening atmosphere through the aggression, presumably of the USSR. At the same time, the enormous responsibility resting on his shoulders does not appear to affect Wałęsa. This very popular cover was created by the French graphic artist and cartoonist Jean Sole. The penultimate issue in 1981 was also devoted to Polish subject matters. The cover of issue 52/1981 referred directly to the state of emergency proclaimed on 13 December. (Fig. 15) The photomontage shows General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who was at the head of the State after martial law was introduced. In the background you can see soldiers of the Polish People’s Army (Ludowe Wojsko Polskie). The cover story of this issue is called “Partei am Ende – Militär soll Polen retten” (“Party finished – Military to rescue Poland”). In this context, the cover of issue 2/1982 in the January of that year can be seen as a continuation of the theme. (Fig. 16) It takes up the previously mentioned historical and geopolitical developments in Poland after 1945. The cover story of this issue explained the significance of Poland to the USSR and the system of the Eastern Bloc states to the West German reader. The photo, with a map shown in the background, portrays the protagonists of the conference of the “Big Three”: Winston Churchill, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin. On the cover is the headline “Jalta 1945 – Wie Polen verkauft wurde” (“Yalta 1945 – How Poland was sold”). The decisive months for Poland between August 1980 and 13 December 1981, when resistance by the opposition was suppressed by the imposition of martial law, were reflected in the magazine’s almost weekly reporting on the current situation, as well as in the covers of the weekly magazine, which were devoted to Poland and its popular representatives. The final cover during this turbulent period related to the situation with the members of the opposition who had been interned by the military dictatorship. (Fig. 17) A photomontage was chosen for the cover of issue 10/1982 from 8 March on which Adam Michnik, one of the most important members of the opposition, can be seen behind a barred cell window. The cover announces “Kassiber an den Spiegel: ‚Wir sind alle Geiseln‘ – Polen-Häftling Michnik über die Militärdiktatur“ (“Secret message to the Spiegel: ‘We are all hostages’ – Poland prisoner Michnik on the military dictatorship”).

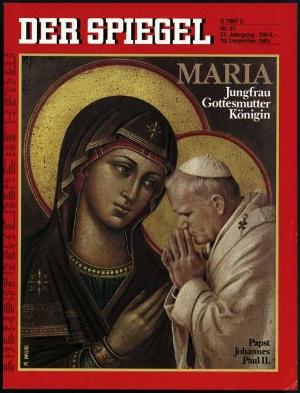

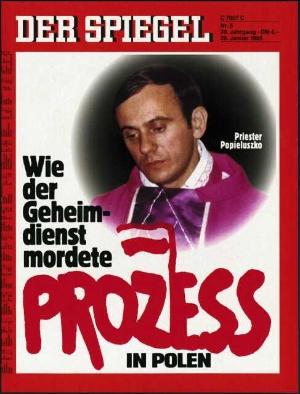

The next three years did not feature any Polish themes on the covers of the magazine. Even when Pope John Paul II was shown on the cover of issue 51/1983, it was without any conscious reference to the social and political situation in Poland. (Fig. 18) As the main story of this issue, the editors dealt with the significance of the adoration of the Virgin Mary in the Catholic Church. On the issue’s cover is Maria, the mother of God to whom John Paul II is praying. Their portrayal is down to the German painter Mathias Waske. The relative stabilisation of the situation in Poland enforced by the military dictatorship was also based on the control of information, only some of which seeping through to Western media was uncensored. Since the official lifting of martial law on 23 July 1983, the Polish authorities were certain in the knowledge that there would be no rapid return to the old dualism, with the party officially representing the interests of society whilst the latter pursued its own grassroots democratic forms of representation of interests. From 1983 to 1987 and 1988, the Hamburg weekly magazine disseminated virtually no communications about Poland or “Polish” covers. During this time, there was only one single cover that addressed a Polish theme by putting the murder of the Solidarność priest Jerzy Popiełuszko from 1984 on the cover. (Fig. 19) Issue 5/1985 of 28 January published a section of a photo of Popiełuszko with the headline “Wie der Geheimdienst mordete – Prozess in Polen” (“How the secret service murdered – Proceedings in Poland”) on the cover, with the word “Prozess” clearly mirroring the font and colour of the word mark Solidarność. The cover story dealt with the proceedings against the Popiełuszko murderers and with the impact of the political murder on the internal affairs of the People’s Republic of Poland.

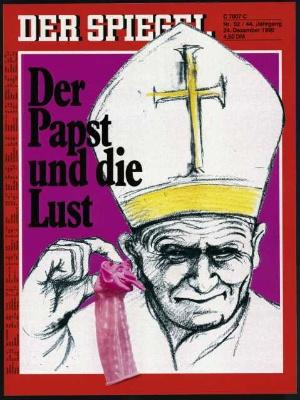

The so-called “Round Table” consisting of the political opposition and the communist government, which began on 6 February 1989 and which ultimately led to a breakthrough giving rise to successive changes to the political system, was not enough to pique the interest of the picture editors at the SPIEGEL. The Western public and the Western media were obviously just as surprised by the establishment and development of Solidarność as they had largely predicted and also expected the process of the decline of the communist system in the Central and Eastern European states. Since 1987, the interest in the changes, which were happening not just in Poland but across the whole Eastern Bloc, has again become a clear priority of the Hamburg magazine. The democratic transformation in Central and Eastern Europe has progressed in many places and spread out widely. In this context, the last cover, which has only a general connection to a Polish theme, can be seen as significant. Pope John Paul II is once more in the centre of the image which was created by the well known French author and illustrator Jean-Thomas “Tomi” Ungerer. (Fig. 20) His cover image shows a caricature of the head of the church at the time. The Pope is holding a pink condom in his hand, the top of which is styled like a gargoyle. The cover story, which deals critically with the prevailing teaching of the Church and of Pope John Paul II on human sexuality, is entitled “Der Papst und die Lust” (“The Pope and the Lust”). All in all, it seems that the political and social situation in Poland at the beginning of the nineties was not so worrying that it needed to feature on the magazine’s cover. In 1989 and 1990, the picture editors at the Spiegel focused on the ever more imminent reunification of the divided Germany, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and in its wake the disintegration of the USSR.

Aleksander Gowin, July 2018

Literature:

Stefan Aust (Hrsg.), Die Kunst Des Spiegel. Titel-Illustrationen aus fünf Jahrzenten, teNeues Publishing Group 2004.

Jochen Bölsche, Rudolf Augstein. Schreiben, was ist. Kommentare, Gespräche, Vorträge, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 2003.

Hans Dieter Jaene, Der Spiegel. Ein deutsches Nachrichten-Magazin, Fischer Bücherei 1968.

Dieter Just, Der Spiegel. Arbeitsweise – Inhalt – Wirkung, Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen 1967.

Peter Merseburger, Rudolf Augstein. Der Mann, der den Spiegel machte, Pantheon Verlag 2009.

Hans-Dieter Schütt, Oliver Schwarzkopf, Die Spiegel-Titelbilder 1947-1999, Schwarzkopf &Schwarzkopf Verlag 2000.

“Der Spiegel”, Special edition 1947-1997, Issue 0/1997.