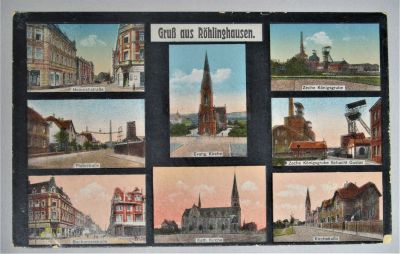

Adalbert and Elisabeth – A Ruhr Polish altarpiece in Herne-Röhlinghausen

Mediathek Sorted

The high altar in Röhlinghausen

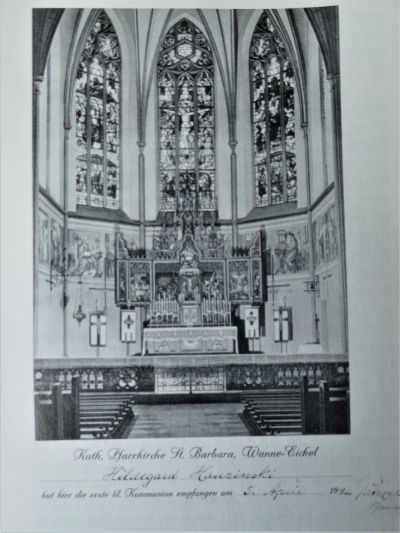

The high altar was commissioned in 1908 and completed in February 1911. The congregation paid the fee of 15,000 reichsmarks in four tranches. The altar was produced collectively by three workshops from the “Wiedenbrück school” in the small town of Wiedenbrück in the eastern Münsterland region, (today: Rheda-Wiedenbrück). There, from around 1845–1945, over 25 companies produced a large number of historical altars, sculptures, stations of the cross and other furnishings, predominantly for Catholic houses of worship. The art workshops, which specialised in different crafts, complemented each other in the production of pieces, and often, individual workshops would collaborate directly with each other.

Production of the high altar in Röhlinghausen was managed by the Becker-Brockhinke cabinet makers, whose owner, Anton Becker (1862–1945) was also responsible for the overall design. The sculptor Anton Mohrmann (1851–1940) worked as a sub-contractor to produce the figures on the front side. The painter Eduard Goldkuhle (1878–1953) completed the colour frame and the partial gilding. He also produced the paintings on the outer sides of the two altar wings, which also show the Holy Adalbert. Mayor Schmitz of Wiedenbrück praised the product of this collaboration in 1923 as one of the most beautiful pieces that had ever left the Becker-Brockhinke workshop. During the 1980s, after the altar was restored, the Paderborn-based company Ochsenfarth described the oil paintings by Goldkuhle as being of the “highest neo-Gothic standard”.

In 1943, during the Second World War, an allied bombing raid destroyed the choir window of St. Barbara in Röhlinghausen. From then on, it became necessary to protect the high altar against weather damage by covering it with a large flag cloth. After three more bombing raids, it was finally removed from the damaged church and taken to Vinsebeck in the Weserbergland region. The altar returned to its original place after the church had been rudimentarily restored from 1945–48. 15 years later, a structural inspection found severe damage to the building caused by the mines below. On 31 December 1963, the church was closed by the building inspectors, and in the autumn of 1965, it was demolished. In 1968/69, a modern church was built on the same site which, being made from concrete, was immune to mining damage. Officially, the new building was consecrated in the name of the Holy Ghost, rather than St. Barbara. By that time, the patron saint of miners had been deleted from the Roman holy calendar during the course of the liturgical reform conducted by the Second Vatican Council, since her existence could not be historically proven. However, parts of the Catholic community – including in Röhlinghausen – refused to accept this decision. The congregation there still refers to itself as “Saint Barbara”.

In the modern church in Röhlinghausen, a side chapel is dedicated to the popular patron saint of mining. The church also contains the high altar from the previous building, albeit in highly modified form. A new altar base has been created, into which a large piece of hard coal from the neighbouring pit known as “Our Fritz” (Unser Fritz) and a receptacle with a reliquary of St Barbara have been incorporated in order to keep the memory of the local mining tradition alive. In the central zone, two narrow panels are missing, which were originally added to the outer sides of the two altar wings. Higher up, it was necessary to remove the neo-Gothic superstructure, since the modern chapel was not high enough to accommodate it.

However, the central image panels have been retained! When folded out, the winged altarpiece shows carved scenes from the Bible. The central scene shows the crucifixion of Christ, and above it the appearance of the lamb from the apocalypse. On the left-hand side, the crucifixion scene is flanked by representations of the birth of Jesus and the wedding at Cana. The right flank shows the adoration of the Holy Three Kings and the transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor. The lower altar zone contains four half-figures of prophets from the Old Testament.

When folded closed, the winged altar shows two oil paintings, each with two holy figures: to the left, Cecilia and Bernhard, and to the right, Elisabeth and Adalbert. Adalbert wears a bishop’s mitre and mass robes. His right hand is raised in blessing. A bishop’s rod leans against his left shoulder. A club in his left hand is a reminder of the violent death suffered by the martyr.

To the left of Adalbert is the Holy Elisabeth, who lived from 1207–1231. In her right hand, she holds a loaf of bread, and in her left, a bowl with red roses. These two attributes stand for the “rose miracle”, a popular legend that tells of the selfless caritas of Countess Elisabeth of Thuringia: During a period of famine, Elisabeth had provided the poor of the town of Eisenach with bread from the Wartburg castle. She did not tell her husband, whom she unexpectedly met during one of her walks through the town, that she was offering help, saying instead that she was carrying roses with her, not bread. Before the count could check her baggage, God had miraculously turned the bread into roses.

There is a particularly charming element in the Röhlinghausen juxtaposition: Bishop Adalbert of Prague became an important national saint in Poland, and also in the Ruhr region, due to the particular circumstances of his burial – the pilgrimage of Emperor Otto III, the raising of the rank of Bolesław Chrobrys, and the establishment of the archbishopric of Gniezno. Countess Elisabeth – who although she was born in Hungary, later did good deeds in Thuringia (in the “green heart” of Germany) – is also regarded as a kind of national saint in Germany. When one looks at the altarpiece, one cannot but view the painting as a symbol of Polish-German history. In this context, it is important to remember that in around 1900, there was considerable tension between the German- and Polish-speaking inhabitants of the Ruhr region. At that time, the authorities adopted various measures in order to pressure the Poles into becoming more German, at a cost to their national identity. The Catholic church was also called upon to support this process, which led to resistance and disputes in many church congregations.

Considering this political and social background, the altarpiece in Röhlinghausen can be interpreted as an appeal for a peaceful coexistence between people and ethnic groups of different nationalities. This appeal still resonates today – and not just in the “melting pot” that is the Ruhr region.

Thomas Parent, July 2023

Selected Bibliography:

Aus der Geschichte der katholischen Kirchengemeinde St. Barbara in Röhlinghausen 1886-1902, Herne o.J. [2002].

Große-Hovest, Benedikt: Die Firma Becker-Brockhinke. Eine Altarbauwerkstatt des Historismus, Aachen 1998.

Haida, Sylvia: Die Ruhrpolen. Nationale und konfessionelle Identität im Bewusstsein und im Alltag 1871-1918, phil. Diss. Bonn [masch.] 2012.

Parent, Thomas: Appell für ein friedliches Zusammenleben von Deutschen und Ruhrpolen. Anmerkungen zu einem Altarbild in der katholischen Kirche von Herne-Röhlinghausen, in: Der Emscherbrücher, Vol. 13 (2005/06), Herne 2005, p. 19–25.

Peters-Schildgen, Susanne: „Schmelztiegel“ Ruhrgebiet. Die Geschichte der Zuwanderung am Beispiel Herne bis 1997, Essen 1997.

Royt, Jan: Hl. Adalbert, Regensburg 1997.

Spieker, Brigitte und Rolf-Jürgen Spieker: In unvergleichlicher Pracht auf Goldgrund gemalt. Die Wiedenbrücker Maler Georg und Eduard Goldkuhle, Bramsche 2019.