Mariusz Hoffmann – from a village in Silesia to Werne and then Berlin

Mariusz Hoffmann was born in 1986, in the hospital in Strzelce Opolskie. His family lived in the nearby village of Zalesie. There, the Hoffmanns lived in a residential estate consisting of just four low-rise apartment blocks. All around them were fields, meadows, the odd house, and a great deal of farmland. The village had pretty much everything that its residents needed: a school, a kindergarten, a farm, which at that time was still operational, a cemetery, of course a chapel, a voluntary fire brigade and, opposite the fire station, the village tavern. Hoffmann’s childhood in Poland was limited to this small world. He recalls that at that time, it still felt quite large and exciting. However, looking back, he can already see a tendency to want to up and leave, even as a little kid. He recounts one of his earliest memories: “I wasn’t even four, and my friend Mirek was five. We tried to walk to the next village on foot, where Mirek’s mother lived at that time. We tried to get there all by ourselves by following the ditch that ran alongside the country road. However, a neighbour passed us by on his tractor, and from where he was sitting high up, he noticed us and put an end to our adventure.”

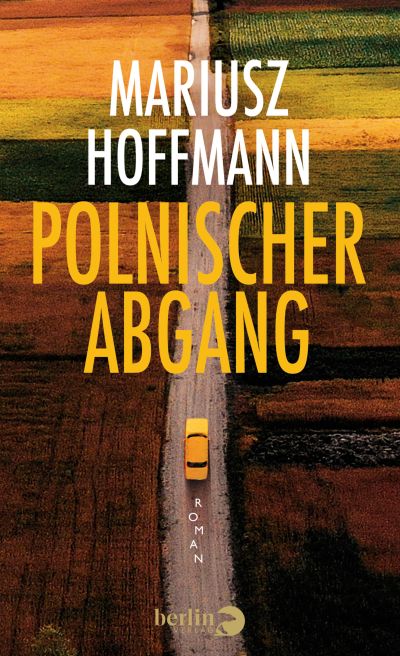

In 1990, the young Mariusz set out on a much longer journey. At the invitation of his grandmother, he and his parents left the small village for Germany. Officially, they should have submitted an application to the Polish authorities for permission to travel on holiday – a long, drawn-out process. In reality, however, the Hoffmanns simply gave up their home in Zalesie and arranged for acquaintances from Germany to come and collect them. They then travelled to North Rhine-Westphalia with just a few belongings, intending to remain there. In Poland, Mariusz’ mother had worked as an accountant in the local agricultural operation; his father was a miner. In Germany, they sought to create a better life for themselves and their son. As Mariusz Hoffmann explains: “The 1970s and 1980s were hard times in Poland. Economically, politically. When the opportunity arose to leave Poland and try their luck in Germany, my parents seized it.” At that time, Hoffmann says, Germany was considered by many people living in Poland to be the land of milk and honey. Especially in a small village in Silesia, the name of which means “behind the forest”, the faraway neighbouring country was thought to be a magical place where anything was possible.

“There was this joke”, Mariusz Hoffmann recalls, “where an old man receives a package from Germany. It contains a glasses frame without the lenses. He puts on the glasses and says: ‘Wonderful. Thanks to the German frame, I can already see much better!’”

The Hoffmanns were more realistic in their expectations. They already had experience of financial hardship and had made preparations to build a new life, even under difficult conditions. Finally, after multiple retraining and further education courses, his mother succeeded in finding a foothold as an office administrator. His father found employment as a technician with a coating company. Their path to an ordered civilian life in Germany followed the typical route: a night in Hamm, then to the camp in Unna-Massen, from there to the sports hall of the Barbaraschule school in Werne, to temporary shared accommodation on the edge of town, and finally, after over two years, they were able to move to a real flat of their own, with their own bathroom and kitchen. At first, young Mariusz wasn’t at all happy in this strange country. In kindergarten, he played by himself, since the other children didn’t understand a word he said. While he was able to pick up German quite quickly, the period of isolation and exclusion lasted a sufficiently long time to leave a lasting impression on him. It was of little use that he had inherited his father’s German surname and that his two grandmothers both spoke German, albeit a very old-fashioned variant. And anyway, his grandparents’ generation, who had memories of the Second World War, preferred to speak Polish whenever they could.