Mariusz Hoffmann. From a village in Silesia to Werne and then Berlin

Mariusz Hoffmann was born in 1986, in the hospital in Strzelce Opolskie. His family lived in the nearby village of Zalesie. There, the Hoffmanns lived in a residential estate consisting of just four low-rise apartment blocks. All around them were fields, meadows, the odd house, and a great deal of farmland. The village had pretty much everything that its residents needed: a school, a kindergarten, a farm, which at that time was still operational, a cemetery, of course a chapel, a voluntary fire brigade and, opposite the fire station, the village tavern. Hoffmann’s childhood in Poland was limited to this small world. He recalls that at that time, it still felt quite large and exciting. However, looking back, he can already see a tendency to want to up and leave, even as a little kid. He recounts one of his earliest memories: “I wasn’t even four, and my friend Mirek was five. We tried to walk to the next village on foot, where Mirek’s mother lived at that time. We tried to get there all by ourselves by following the ditch that ran alongside the country road. However, a neighbour passed us by on his tractor, and from where he was sitting high up, he noticed us and put an end to our adventure.”

In 1990, the young Mariusz set out on a much longer journey. At the invitation of his grandmother, he and his parents left the small village for Germany. Officially, they should have submitted an application to the Polish authorities for permission to travel on holiday – a long, drawn-out process. In reality, however, the Hoffmanns simply gave up their home in Zalesie and arranged for acquaintances from Germany to come and collect them. They then travelled to North Rhine-Westphalia with just a few belongings, intending to remain there. In Poland, Mariusz’ mother had worked as an accountant in the local agricultural operation; his father was a miner. In Germany, they sought to create a better life for themselves and their son. As Mariusz Hoffmann explains: “The 1970s and 1980s were hard times in Poland. Economically, politically. When the opportunity arose to leave Poland and try their luck in Germany, my parents seized it.” At that time, Hoffmann says, Germany was considered by many people living in Poland to be the land of milk and honey. Especially in a small village in Silesia, the name of which means “behind the forest”, the faraway neighbouring country was thought to be a magical place where anything was possible.

“There was this joke”, Mariusz Hoffmann recalls, “where an old man receives a package from Germany. It contains a glasses frame without the lenses. He puts on the glasses and says: ‘Wonderful. Thanks to the German frame, I can already see much better!’”

The Hoffmanns were more realistic in their expectations. They already had experience of financial hardship and had made preparations to build a new life, even under difficult conditions. Finally, after multiple retraining and further education courses, his mother succeeded in finding a foothold as an office administrator. His father found employment as a technician with a coating company. Their path to an ordered civilian life in Germany followed the typical route: a night in Hamm, then to the camp in Unna-Massen, from there to the sports hall of the Barbaraschule school in Werne, to temporary shared accommodation on the edge of town, and finally, after over two years, they were able to move to a real flat of their own, with their own bathroom and kitchen. At first, young Mariusz wasn’t at all happy in this strange country. In kindergarten, he played by himself, since the other children didn’t understand a word he said. While he was able to pick up German quite quickly, the period of isolation and exclusion lasted a sufficiently long time to leave a lasting impression on him. It was of little use that he had inherited his father’s German surname and that his two grandmothers both spoke German, albeit a very old-fashioned variant. And anyway, his grandparents’ generation, who had memories of the Second World War, preferred to speak Polish whenever they could.

Mariusz Hoffmann began writing when he was eleven. It started with a diary, then long letters, which he sent to various penpals in the post. At 20, he used narrative passages from his letters as starting material for short stories. “Even then”, he recalls, “I nurtured a secret hope that I would reach a larger readership.”

He has his grandmother Agnieszka to thank for his fascination for short stories. In his eyes, she was the best storyteller during his childhood. He loved it when she put everything she had into recounting memories, or telling fairytales or gruesome real-life stories. “Her voice sounded different when she was telling stories”, he says. “I was enthralled every time.” In this way, he developed his love of reading at a young age. When he read particularly gripping books, he thought: “I want to do this, too. Write in an exciting, pointed, humorous way. Not just for me, but for other people.”

In his youth, there were numerous authors whose books he loved. However, one key moment for him came in 2006, when he bought Irvine Welsh’s novel “Trainspotting” for one Euro at a flea market in Hamburg. He recalls: “I was familiar with the film of the same name. I didn’t know that it was based on a novel. Without knowing what to expect, I started reading the book, and was blown away. This style of writing, the characters, the moods, the critical jibes against Scottish society... For me, it was a revelation in terms of all the possibilities that literature has to offer.”

But how to become an author? Especially when for your family, “literature” is an exotic hobby for wealthy people. Like many other writers, Mariusz Hoffmann’s life took on several interesting twists and turns prior to his becoming a writer. After taking his “Abitur” school-leaving exams, he first spent a period of time as a civilian volunteer in Hamburg (in lieu of mandatory military service – translator’s note). He then enrolled as a student of philosophy in Hamburg, although he soon realised that this was not for him. He decided to do something “normal” and took a job with an institution for young adults with behavioural problems. Since he wasn’t entirely happy working there, he applied to study in Leipzig and Hildesheim, the only places in Germany offering a degree in creative writing. When his application was accepted by the University of Hildesheim, he was euphoric. He remembers that the other students in his year had similar feelings. “However, by the third semester at the latest, the euphoria had vanished”, he explains. “Now there were periods when everything that we wrote suddenly sounded banal and bad, and the doubts grew as to whether we had what it took to become an author in the first place.”

The many meetings, during which the students talked about their own texts and those written by others, only served to exacerbate this self-doubt. On the other hand, Hoffmann regards these discussions particularly as being the most important aspect of the degree course. In his mind, the comments that were made, including the ones that hurt, helped a great deal when it came to improving his own writing and sharpening his sense of when a text worked well and sounded good.

In Hildesheim, the would-be authors not only learned how to critically discuss their writing, but also that there are far more opportunities to work in the cultural sector than purely as a writer. Hoffmann names several examples: organising cultural events, editing, writing contributions for radio, blogging, and formats such as “Litradio” or the literary journal “Bella triste”, where he worked as a co-publisher. During periods of self-doubt, it was this perspective that prevented him from becoming too discouraged. In the event, Hoffmann applied for numerous literary grants during his time as a student in Hildesheim. Often, he was turned down, and patience and the ability to deal with his sense of frustration were required. Finally, however, his perseverance paid off, and he was awarded writing residencies in Broumov in the Czech Republic and Ahrenshoop on the Baltic coast.

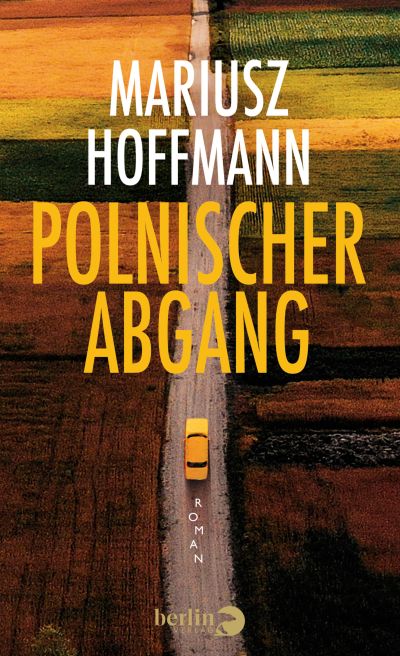

During these residencies, he wrote the short story “Dorfköter” (“Village Mongrel”). The narrative is told in the first person, and follows the story of a boy who leaves his Silesian village of Zalesie with his parents and comes to Germany. Originally, Hoffmann hadn’t planned on writing autobiographically, and hadn’t wanted to use his own family history as a starting point. During the process of writing, however, it became impossible to ignore the material. The story centres around the loss of a friendship. However, the text was imbued with Hoffmann’s childhood memories, and with descriptions of the rural village where he grew up. In the prestigious open mike writing competition, Hoffmann won first prize in the “prose” category with “Dorfköter” in 2017. The award, as well as the positive reception of the story, encouraged him to expand on the material. He conducted interviews with his parents and grandmother, and tried to retrace his family history. Finally, he had more than enough material to send the Sobota family in the novel off on their journey. However, before the book, entitled “Polnischer Abgang” (“Polish Departure”) was published by the berlin Verlag, Mariusz Hoffmann first completed his studies in Hildesheim, moved to Berlin, took up employment as a care assistant and honed his manuscript after the end of the working day. Finally, he found his publisher through an agent. He recalls his parents’ reaction: “At first, they were sceptical when I told them I was writing a book. But when things got serious with the publisher, they were delighted that their son had become something so unusual like an author.”

“Polnischer Abgang” is a tragi-comic family road trip novel. In 2023, it was nominated for the Ruhr literary prize and was praised by Nico Bleutge on Deutschlandfunk radio as being “magically strange” and “highly perceptive”. However, in an article for the Deutsches Polen Institut, the Silesian specialist in German language and literature Andrzej Kaluza criticises Hoffmann’s novel, saying that it follows in the tradition of other accounts of Polish emigration that mix fact and fiction and which are ultimately not credible. As Mariusz Hoffmann explains: “This is a novel, not a non-fiction book. The first-person narrator is young and unreliable, and is not interested in ‘identities’. My claim to truth has nothing to do with the correct rendition of the history of Upper Silesia, but rather with the truthful rendition of a subjective perspective. When I developed the character of Jarek, I based him on the young people I met in Zalesie and Strzelce when I travelled there myself as a young man. They’re boys from simple backgrounds. It’s possible that Mr. Kaluza is not very familiar with them.”

Today, Hoffmann works as a freelance author and creative writing teacher. He also has a regular job teaching language courses. Additionally, he is working on a new novel, although he is reluctant to say much about it at this stage. He is willing to reveal one thing, though: in the new novel, the main character is also searching for a place to call home.

He travels to Poland two or three times a year. This summer, he will visit Warsaw for the first time, and is looking forward to speaking Polish in public again without making himself conspicuous.

Anselm Neft, August 2024