The story of Herschel Grynszpan

Propaganda, the Reich Pogrom Night and the (planned) show trial

Meanwhile, in the German Reich, events were moving very fast. Already on the day of the attack, the top leadership of the National Socialist party, led by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, launched a nationwide antisemitic propaganda campaign. The key message of this campaign was that the assassination in Paris was an “attack by global Jewry” against the German Reich; “the Jews” were the real “criminals against peace in Europe”. On the evening of 7 November 1938, in an atmosphere of violence that had been exacerbated by such propaganda, the first anti-Jewish riots took place in several towns and villages in the counties of Kurhessen and Magdeburg-Anhalt. This unrest continued through into 8 November.[22] By pure chance, when Ernst vom Rath succumbed to his injuries on the late afternoon of 9 November, nearly the entire high-level Nazi leadership, as well as numerous “Reichsleiter” national leaders, “Gauleiter” regional leaders and SA and SS leaders, were gathered in Munich for a collegial meeting and to commemorate the Hitler putsch of 9 November 1923. During the festive dinner, Hitler was informed by Goebbels about vom Rath’s death and the individual pogroms in Kurhessen and Magdeburg-Anhalt. Hitler then ordered his propaganda minister to allow the unrest to continue and to withdraw the police presence. After this intense discussion with Goebbels, Hitler left the meeting without speaking before the gathering. Goebbels first passed on the order internally to the police and party leaders, before rising to give an incendiary antisemitic speech. Now, the National Socialist propaganda had a “German martyr” and a “murderous Jewish lout” to work with – welcome grounds for hitting out against the “Jewish global conspiracy” with acts of violence. When they heard his words, all the party functionaries present hurried to the telephones and telegraphs. Within just a few hours, the verbally given order had reached all the regional party offices throughout the country. The “spontaneous fury of the people” that was unleashed during the Reich Pogrom Night, and which is regarded as one of the darkest chapters in German history, had devastating consequences: 1,400 synagogues and prayer rooms, as well as thousands of shops and apartments owned by Jewish citizens were destroyed, plundered or set on fire. Around 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and deported to concentration camps, while hundreds more were maltreated and murdered in prison.

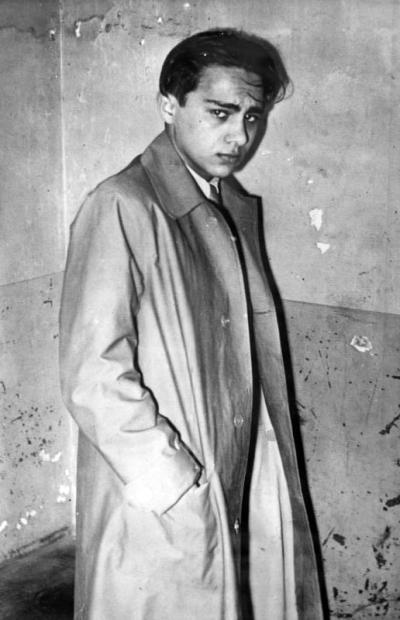

Herschel, who was horrified to hear the following day about what had happened from the French press, was now being held in custody in the youth prison in Fresnes. Now, following the death of Ernst vom Rath, he was facing trial for murder, which the National Socialist propagandists planned as a show trial to represent the “cardinal sin of global Jewry”. Although according to French law and the fundamental principles of international law, the German Reich was only authorised to participate in the forthcoming trial through vom Rath’s family as a civil party, the National Socialists immediately began with their own extensive inquiries and preparations for the trial. Hitler named the antisemitic, National Socialist lawyer Friedrich Grimm as the government’s representative in the proceedings. Grimm had already stood out for his achievements in combating resistance fighters and opponents of the Nazi regime. Extensive investigations began in cooperation with the Nazi propaganda ministry, which aimed (in vain) to present Herschel Grynszpan, who was just 1.54 m tall, as a “thuggish type” with a “criminal past”, as well as to uncover his alleged criminal backers. They planned to include only a sugar-coated version of the real circumstances of the “Polish Action” and the expulsion of Herschel’s family in the proceedings – if at all.

During the first weeks and months following the crime, Herschel became an “international star”, with reports about him in many newspapers in Europe and the US.[23] He was not least made aware of the high level of interest in him as an individual and the importance of the forthcoming trial by the presence of willing criminal attorneys and star lawyers who were sent by the leaders of the French Fédération des sociétés juives, and who were supported and funded by organised groups representing the interests of Jews.[24] He also received letters in prison – mostly from people who wished him well, but also from those who condemned him for what he had done. Herschel, who was likely concerned about the divided public opinion regarding the crime, and who therefore felt under strong pressure to justify his actions, wrote letters to his deported family in Poland and to relatives and friends in Germany and France. It was surely no coincidence that through his lawyers, these letters found their way into the international press and were made accessible to the general public.

“Everything is churning around in my head. My God! Do you really think that I’m the reason for the present catastrophe that has befallen the Jews? This thought drives me mad. [...] I live only to be able to tell the world at my trial that it must do something for us.”[25]

Herschel wrote these words in a letter to a friend, which was published at the start of December 1938 in the Jewish newspaper “Zeit” in London, and later in several French publications.

On 8 June 1939, the French investigative judge officially brought charges against Herschel. The proceedings against Herschel were postponed multiple times by the French authorities, despite pressure from the National Socialist government. However, soon afterwards, the pending trial was entirely eclipsed by events elsewhere. For Herschel’s parents, who had travelled on from the barracks camp in Zbąszyń to Radomsko, then on to Polish relatives in Łódź, and finally to Warsaw, the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 came as a shock.[26] Britain and France declared war against Germany on 3 September. The western campaign began on 10 May 1940. On the day Germany attacked France, Herschel was being held in the youth custody facility in Fresnes. On 12 June 1940, as the German Wehrmacht continued to advance through the country, he and 96 other prisoners were transported to Bourges in southern France under French guard. When they arrived in Bourges, they were met with chaotic scenes. The town was overfilled with refugees from the north of France. People were terrified of the German troops, who were already coming threateningly close to the town. Although he was aware that the Gestapo had their sights on the famous 17-year-old prisoner, and that they would probably have him summarily shot, the director of the prison in Bourges refused to take Herschel in. Herschel had no alternative but to continue to flee from the Germans alone on foot in the direction of Chateauroux. However, there, too, he was refused entry at the prison gates. On 10 July 1940, he finally reached Toulouse. There, on the following day, he fell into the hands of the Germans.[27]

On 14 July, he was handed over to the Gestapo and immediately taken to Berlin, where he was first held in police custody in Moabit. On 18 January 1941, he was taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was held in the “Zellenbau” isolation cells and given preferential treatment. On 16 October 1941, the German Reich pressed its own charges against Herschel, citing murder and high treason and without allowing him access to a defence lawyer. However, since the preparations for the trial did not go as planned by the National Socialist functionaries, the start of the trial was repeatedly postponed. During the unbearably long period of waiting for his trial, which was to be held in Nazi Germany and which he had no hope of winning, Herschel clearly attempted to take his own life and went on hunger strike multiple times.[28] As the planned trial date neared, his situation become significantly worse. He was kept in chains 24 hours a day. However, in the end, the trial never took place. Due to the high losses that were now being incurred by the German Wehrmacht on the eastern front and the rapid decline in support among the German population for initiating costly proceedings against Herschel, the show trial was postponed indefinitely on the orders of Adolf Hitler. Grynszpan is last mentioned in the German records in September 1942, shortly before a mass murder campaign in Sachsenhausen in which a large number of prisoners were killed. There, the trail goes cold.