The story of Herschel Grynszpan

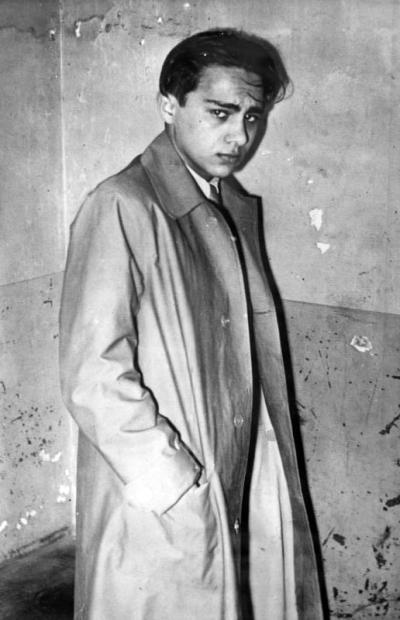

The Reich Pogrom Night from 9 to 10 November 1938 is rightly accorded an important and separate place in history books and in the public discourse surrounding National Socialism. It marks a turning point in National Socialist policy, in which the party’s anti-Jewish strategy suddenly shifted from the exclusion and disenfranchisement of Jews to their systematic divestment, persecution and expulsion. In the interim, a large number of historical studies have been published about the Reich Pogrom Night and the events that preceded the appalling exclusion from everyday life of fellow Jewish citizens in many parts of the German Reich. Less well known is the story of the 17-year-old Grynszpan, whose assassination of the Second Secretary at the German Embassy was used by the Nazi leadership as a pretext for the brutal violence that followed, and who tragically became a key figure in world history. Even as late as the 1980s, he was merely referred to in school textbooks as a nameless “Jewish boy”.[1] It was only during the course of more recent historical research that both the assassination itself and the motives for his actions and his family history became the focus of several less scientific analyses. He was also finally referred to by his name: Herschel Feibel Grynszpan.

Pogroms, migration and a new start in Germany

The fates and life stories of Jews in Germany and Europe are varied and tragic. They act as a warning, filling several hundred metres of bookshelves in historical archives all around the world. From antiquity to the modern era, a Christian-western enmity of Judaism became firmly established that was fed by anti-Jewish myths, nationalism and social Darwinism. In the 20th century, these attitudes would take on a hitherto unknown, horrific dimension. Just one example of the scale of European antisemitism during the 20th century is the (migration) story of the Grynszpan family, which began in 1911, in the small village of Dmenin near Radomsko, in the Russian-occupied region of Poland[2]. In addition to their financial hardship and the political tensions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews in eastern Europe were confronted with numerous restrictions and increasing incidences of violence. For many people of the Jewish faith, the decision to emigrate from their homeland to the west in the decades that followed was first sparked by the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire in 1881. By the early 1920s, nearly three million Jews had fled eastern Europe. In 1911, the Jewish-Polish couple Ryfka (née Silberberg, *1887) and Sendel Grynszpan (*1886), who were still childless at that time, fled from Russian-controlled Poland to Germany. Like many others of the Jewish faith, they hoped to escape from poverty, as well as from the increasing number of antisemitic laws and attacks on the Jewish community. It was a hopeful new beginning.

The young couple settled in Hanover. The Prussian provincial capital had flourished as a result of the economic boom that occurred in the 19th century during the Gründerzeit period, and continued to enjoy the economic growth brought by industrialisation. While the population totalled just under 100,000 in 1874, by 1911, it had grown to over 308,000.[3] Already in 1870, the Jewish community in Hanover, which was also growing, consecrated a new, larger synagogue in Bergstrasse in the old town quarter, right next door to the main Christian churches there. The Grynszpans’ new home was one of the main economic, cultural and industrial centres in Germany, with a vibrant Jewish community.

Sendel Grynszpan earned his living as a master tailor, with his own shop in Knochenhauerstrasse 5 in the old town district of Hanover. In 1914, Ryfka’s and Sendel’s oldest child, Sophia Helena, was born. The following year, Sendel moved his tailor’s business to the neighbouring Burgstrasse 36 and the young family relocated to a modest apartment of just 40 square metres on the second floor above the shop. By 1920, this cramped space had become home to three more children[4]: Esther Beile, known as Berta (*1916), Mordechai Eliezer, known as Markus (*1919) and Salomon (*1920). Ryfka and Sendel brought their children up in the Jewish faith. They were highly respected members of the Jewish congregation and observed the traditional religious customs in their daily lives. However, at the same time, they were also open to the modern way of thinking of the western European Jews, who wanted to adapt to the culture and way of life in Germany. The Grynszpans educated their children in German and called them by German names. At home, however, the family mainly spoke Yiddish. The parents did not teach their children Polish, their language of origin.

They were certain they would never be able to return to Poland. However, suddenly and unexpectedly, the Grynszpan family, now six people in all, were granted Polish citizenship. After having being partitioned for 123 years, Poland had regained its independent statehood after the end of the First World War. The first legal regulation relating to Polish citizenship was the Polish Citizenship Act of 20 January 1920, which granted Polish citizenship not only to all those living in Polish territory, but also to people who were born in Poland and who were not eligible to become citizens of another country.[5] Since Sendel and Ryfka’s place of birth, Radomsko, was in Polish state territory, and since they had neglected to submit an application for naturalisation in Germany, they received Polish citizenship, which was also conferred on their children born in Germany.[6] Their youngest son, Herschel Feibel, known as Hermann, who was born on 28 March 1921, therefore came into the world as a Polish Jew in Germany.

[1] https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-euv/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/766/file/Fuhrer-2014-Herschel.pdf (last accessed on 24/11/2020).

[2] Following the three gradual partitions of Poland by the neighbouring powers of Prussia, Austria and Russia, Poland was divided up into three separate regions, and vanished from the map of Europe as a sovereign state from 1795 until the end of the First World War.

[3] See: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einwohnerentwicklung_von_Hannover (last accessed on 23/4/2021).

[4] Records show that Ryfka Grynszpan gave birth to seven children overall. Three of them died during birth or in infancy: no name (*/†1912), Ida (*/†1918) and Charlotte (*/†1922).

[5] https://web.archive.org/web/20140220045204/http://de.yourpoland.pl/userfiles/pdfs/ustawa-1920-de.pdf (last accessed on 23/4/2021).

[6] Armin Fuhrer, p. 28.

Economic crisis, antisemitism and an (illegal) departure for France

Herschel Grynszpan’s family were not only directly affected by the new borders that had been drawn in the wake of the First World War, but also by far reaching economic, political and personal events. Like everywhere else in the young Weimar Republic, the currency debasement that occurred between 1918 and 1923, coupled with the global economic crisis from 1929/1930, had a noticeable impact on the economy and on everyday life among the population at large in Germany. Social decline, unemployment and homelessness threatened many millions of people, and the sense of catastrophe that dominated among the population in general also brought about a change in political attitudes. The Grynszpan’s business began to struggle financially, until finally, Sendel was forced to abandon his tailor’s shop from 1930 to 1933 and open a store selling second-hand goods in Burgstrasse 19. The family lived in impoverished circumstances, and also suffered personal tragedies as well as increasing discrimination. In 1928, the oldest daughter Sophia Helena died aged about 14; in 1931, the second-youngest son, Salomon, died aged 11. When the National Socialists came to power on 30 January 1933, hatred of Jews became state doctrine. Attacks against Jewish fellow citizens in broad daylight, anti-Jewish boycotts, blockades and looting of Jewish shops were now part of the standard repertoire of National Socialist policy and those who implemented it. The second-oldest daughter Beile (Berta) felt the impact of the anti-Jewish sentiment very clearly when she was unable to find a job after passing her school leaving exams. The youngest child, Herschel, who was physically very delicate and noticeably too small for his age, left secondary school in 1935 without any qualifications and moved to the rabbinical academy in Frankfurt/Main for training in the Hebrew language. Although the rabbis and teachers attested to his great sense of justice, vivaciousness and impulsiveness, as well as his above-average intelligence and interest in politics, he did not do so well when it came to hard work, attention to detail and enthusiasm. He abandoned the training after just a few months. For the 15-year-old boy, with his Jewish faith and Polish citizenship, there appeared to be no realistic prospect of being offered either a traineeship or a job in Nazi Germany.

As a result of the increasingly aggressive antisemitism in Germany, Herschel and his family considered leaving the country. Herschel hoped to be able to emigrate to Palestine, the most important country of exile for Jewish refugees from Europe since the National Socialists came to power in 1933. In July 1936, hopeful of travelling to the “promised land” and glad to be rid of the humiliation of living under the National Socialist regime, the 15-year-old Herschel first decided to turn his back on the country alone and to travel on a Belgian visa to his uncle, Wolff Grynszpan, who lived in Brussels. There, he waited to obtain the certificate needed from the British mandate government allowing him to travel to Palestine. However, the increasingly restrictive immigration policy pursued by the British mandate government meant that Herschel, like many other Jews at that time, was denied permission to do so.[7] Since Herschel, who had no source of income, was not welcome to stay with his uncle Wolff in Brussels in the long term, he took up an invitation from his uncle Abraham and his wife Chawa, who lived in Paris, to come and live with them. In August/September 1936, Herschel illegally crossed the Belgian-French border and travelled to Paris – in contravention of the passport and outward travel regulations. This would later prove to be his downfall.

In Paris, Herschel occasionally helped his uncle Abraham out with his work, but did not take on regular employment. Although he certainly struggled with the French language, he pursued a wide range of activities typical of boys of his age. He trained at the “Aurore” Jewish sports club with friends from the local Jewish community, as well as dances in the 10th arrondissement and the Paris “demi-monde” around the Boulevard St. Martin.[8] He sent reports of his life in Paris in frequent letters to his family, who had remained in Hanover and who had originally planned to follow him to France. However, as a result of the entry bans for Jews travelling from Germany to France, all attempts by Ryfka and Sendel Grynszpan to join their son came to nothing.[9]

At the same time, the teenage Herschel found himself in the midst of a frustrating paper chase, involving application forms, official letters and games of hide and seek – as well as omissions for which he only had himself to blame. In April 1937, Herschel’s application to obtain indefinite permission to stay in France failed because he had previously entered France illegally and therefore had no stamp in his passport marking his arrival in the country.[10] The prospect of obtaining an entry visa overseas – to Palestine or the US – also remained elusive. In desperation, and against the background of the continued escalation in antisemitic violence, Herschel even wrote a letter to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt, asking him to grant him and his family asylum. However, by this time, the US had also closed its doors to Jewish refugees.[11]

On 1 April 1937 – most likely due to his own negligence in solving the problems with his passport on time – the validity of his return visa to Germany expired without his having applied for an extension. When his Polish passport also expired on 1 February 1938, Herschel approached the Polish consulate in Paris to apply for a new one, which he soon received. However, the German authorities were unwilling to issue him a new return visa to Germany on the basis of his new Polish passport. For them, Herschel officially became a foreign Jew intending to enter Germany for the first time following the expiry of his old passport and visa.[12] Why should the Germans allow him to re-enter the country when they were glad to be rid of every Jew who found themselves outside German territory? Herschel was therefore banned from entering Germany, and returning to his family. In the summer of 1938, his already difficult situation became even worse: on 8 June of that year, Herschel received an injunction from the French Ministry of the Interior requiring him to leave France by 15 August, due to the expiry of his residence permit.[13] Threatened with deportation from France, but without the possibility of returning to Germany, Herschel turned to hiding in a small attic room with relatives, never daring to leave the house during the day. Finally, on 15 October 1938, the Polish state issued a decree stating that Poles who had lived abroad for five years without interruption would lose their citizenship on 29 October. At the end of October 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, now 17 years old, became a stateless person.[14]

[7] https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/gerettete-geschichten/149158/palaestina-als-zufluchtsort-der-europaeischen-juden (last accessed on 23/3/2021); Armin Fuhrer, p. 49.

[8] Armin Fuhrer, p. 36.

[9] Armin Fuhrer, p. 37.

[10] Armin Fuhrer, p. 45.

[11] Armin Fuhrer, p. 39.

[12] Armin Fuhrer, p. 46 ff.

[13] Armin Fuhrer, p. 49.

[14] https://www.fritz-bauer-institut.de/fileadmin/editorial/download/publikationen/PM-03_Novemberpogrome-1938.pdf , p. 49 (last accessed on 24/11/2020).

The “Polish Action”, a postcard, and the assassination

At the same time, as a result of the Polish decree of 15 October 1938, Herschel’s family met with the same tragic fate as thousands of other Jews living in the German Reich who had emigrated from Poland. On 28 and 29 October, after the Polish state announced its decision to withdraw Polish citizenship from Poles who had been living outside Poland without interruption for more than five years, the National Socialist regime arrested around 17,000 Jews with Polish citizenship who were living in the German Reich, forcibly brought them to the Polish border, and expelled them from the country. Records show that the 484 people were expelled from Hanover, including the Grynszpan family. They were deported by train to Bentschen (Zbąszyń) near the German-Polish border on 28 October, where they were forced to cross the border on foot by German police and guards.[15] The relentless forced deportation of thousands of Jews from Germany came as a complete surprise to the Polish border officials, who were entirely unprepared for what happened. The Polish authorities and population on the other side of the border had no means of providing sufficient food and shelter for such a large number of people. On 29 October 1938, father Sendel, mother Ryfka and Herschel’s siblings Berta and Markus found themselves in the small Polish village of Zbąszyń along with around 12,000 other deportees, where they were hurriedly placed in emergency shelter in barracks in catastrophic conditions.[16]

On 3 November 1938, Herschel received a postcard in Paris from his sister, who described the dramatic fate of his family during the “Polish Action” (“Polenaktion”):

Dear Hermann!

You will surely have heard of our great misfortune. Let me describe what happened. On Thursday evening, rumours were circulating that all Polish Jews were to be expelled from a city. Even so, we found them difficult to believe. On Thursday evening at 9, a policeman came to us and told us that we should go to the police station with our passports. All together, as we were, we went to the police station accompanied by the policeman. We found almost our entire district gathered there. A police car immediately took us to the city hall. Everyone was taken there. No-one told us what was going on. However, we could see what they had in mind.

Each one of us was handed an expulsion order. We were told we had to leave Germany before the 29th. We were no longer allowed to return home. I begged them to allow me to go home to at least collect a few things. I then left for home, accompanied by a policeman, and packed the most important items of clothing in a suitcase. That’s all that I was able to save.

We don’t have a single penny on us. [...] I’ll tell you more next time.

Love and kisses from us all

Berta

Zbąszyń, 2nd barracks, Grynszpan[17]

Several days after receiving this upsetting news, Herschel, in his desperation and helplessness, was overcome with impulsive, erratic thoughts of sending all his savings to his family. However, he was persuaded not to do so following an argument with his uncle Abraham.[18] Indeed, there was no guarantee that the money really would reach his family in Poland. After the dispute with his uncle, Herschel left the apartment where his uncle and aunt lived on 6 November 1938 with some money that his uncle had given him, announcing that he wouldn’t be coming back. He spent the night at the hotel “Suez” on Boulevard Strassbourg 17, registering under a false name.

The next morning, on 7 November 1938, Herschel left the hotel at around 8:30 am. In the general store “A la Fine Lame” in the Rue du Fauburg St. Martin 61 in the 10th arrondissement, he bought a calibre 6.25 double-action revolver and 25 cartridges for 235 francs. When asked by the salesman why he was purchasing the weapon, he said that it was for self-defence. He then took the metro to the German Embassy in the Rue de Lille, arriving there at 9:30 am. After asking to speak to an embassy secretary, allegedly in order to hand over an important document, he was taken by the embassy assistant to the room where the Second Secretary, Ernst vom Rath, had his office. Herschel suddenly pulled out the revolver after entering the room, shooting five times at Ernst vom Rath, who had jumped up from his chair in alarm. “You’re a dirty German [sale boche]”, he shouted, “and now, in the name of 12,000 persecuted Jews, I’m handing you the document.”

Herschel was arrested without any resistance and taken to the nearby police station. That same day, the 17-year-old was questioned twice by the French police without a legal adviser being present. According to the police record of Herschel’s statement, his decision to shoot an employee of the German Embassy in Paris was made after reading the postcard sent by his sister.[19] During questioning, he gave various different background information, details and motives for the attack. The following day, he was presented before a French examining judge, who again subjected him to questioning. Here, Herschel stressed the following:

“It is important to me to explain to you that my actions did not stem from hatred or vengeance, but from love for my father and my people, who are enduring unimaginable suffering. I regret having injured another person, but I had no other means of expressing my intention.” [20]

After the attack, vom Rath, who was seriously injured by two of the shots, was immediately taken to the Clinique d’Alma close by. He was in a critical condition, but there was still hope that he would survive.[21] Directly following the announcement of the attack, the French doctors treating vom Rath received assistance from Hitler’s personal doctor, Dr Karl Brandt, who flew to Paris on the night of 8 November, accompanied by Prof. Dr Georg Magnus.

On 9 November, the 29-year-old Ernst vom Rath died of his injuries. There is no clear evidence to prove whether or not the National Socialists had intentionally helped vom Rath’s death along in order to instrumentalise him as a “blood witness” for propaganda purposes.

[15] Armin Fuhrer, p. 98.

[16] Armin Fuhrer, p. 98 (translator’s translation).

[17] Source: Federal Archives, Berlin, R 55/20991, letters to and from Herschel Grynszpan

[18] Armin Fuhrer, p. 42.

[19] Armin Fuhrer, p. 41.

[20] Armin Fuhrer, p. 108.

[21] Armin Fuhrer, p. 62.

Propaganda, the Reich Pogrom Night and the (planned) show trial

Meanwhile, in the German Reich, events were moving very fast. Already on the day of the attack, the top leadership of the National Socialist party, led by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, launched a nationwide antisemitic propaganda campaign. The key message of this campaign was that the assassination in Paris was an “attack by global Jewry” against the German Reich; “the Jews” were the real “criminals against peace in Europe”. On the evening of 7 November 1938, in an atmosphere of violence that had been exacerbated by such propaganda, the first anti-Jewish riots took place in several towns and villages in the counties of Kurhessen and Magdeburg-Anhalt. This unrest continued through into 8 November.[22] By pure chance, when Ernst vom Rath succumbed to his injuries on the late afternoon of 9 November, nearly the entire high-level Nazi leadership, as well as numerous “Reichsleiter” national leaders, “Gauleiter” regional leaders and SA and SS leaders, were gathered in Munich for a collegial meeting and to commemorate the Hitler putsch of 9 November 1923. During the festive dinner, Hitler was informed by Goebbels about vom Rath’s death and the individual pogroms in Kurhessen and Magdeburg-Anhalt. Hitler then ordered his propaganda minister to allow the unrest to continue and to withdraw the police presence. After this intense discussion with Goebbels, Hitler left the meeting without speaking before the gathering. Goebbels first passed on the order internally to the police and party leaders, before rising to give an incendiary antisemitic speech. Now, the National Socialist propaganda had a “German martyr” and a “murderous Jewish lout” to work with – welcome grounds for hitting out against the “Jewish global conspiracy” with acts of violence. When they heard his words, all the party functionaries present hurried to the telephones and telegraphs. Within just a few hours, the verbally given order had reached all the regional party offices throughout the country. The “spontaneous fury of the people” that was unleashed during the Reich Pogrom Night, and which is regarded as one of the darkest chapters in German history, had devastating consequences: 1,400 synagogues and prayer rooms, as well as thousands of shops and apartments owned by Jewish citizens were destroyed, plundered or set on fire. Around 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and deported to concentration camps, while hundreds more were maltreated and murdered in prison.

Herschel, who was horrified to hear the following day about what had happened from the French press, was now being held in custody in the youth prison in Fresnes. Now, following the death of Ernst vom Rath, he was facing trial for murder, which the National Socialist propagandists planned as a show trial to represent the “cardinal sin of global Jewry”. Although according to French law and the fundamental principles of international law, the German Reich was only authorised to participate in the forthcoming trial through vom Rath’s family as a civil party, the National Socialists immediately began with their own extensive inquiries and preparations for the trial. Hitler named the antisemitic, National Socialist lawyer Friedrich Grimm as the government’s representative in the proceedings. Grimm had already stood out for his achievements in combating resistance fighters and opponents of the Nazi regime. Extensive investigations began in cooperation with the Nazi propaganda ministry, which aimed (in vain) to present Herschel Grynszpan, who was just 1.54 m tall, as a “thuggish type” with a “criminal past”, as well as to uncover his alleged criminal backers. They planned to include only a sugar-coated version of the real circumstances of the “Polish Action” and the expulsion of Herschel’s family in the proceedings – if at all.

During the first weeks and months following the crime, Herschel became an “international star”, with reports about him in many newspapers in Europe and the US.[23] He was not least made aware of the high level of interest in him as an individual and the importance of the forthcoming trial by the presence of willing criminal attorneys and star lawyers who were sent by the leaders of the French Fédération des sociétés juives, and who were supported and funded by organised groups representing the interests of Jews.[24] He also received letters in prison – mostly from people who wished him well, but also from those who condemned him for what he had done. Herschel, who was likely concerned about the divided public opinion regarding the crime, and who therefore felt under strong pressure to justify his actions, wrote letters to his deported family in Poland and to relatives and friends in Germany and France. It was surely no coincidence that through his lawyers, these letters found their way into the international press and were made accessible to the general public.

“Everything is churning around in my head. My God! Do you really think that I’m the reason for the present catastrophe that has befallen the Jews? This thought drives me mad. [...] I live only to be able to tell the world at my trial that it must do something for us.”[25]

Herschel wrote these words in a letter to a friend, which was published at the start of December 1938 in the Jewish newspaper “Zeit” in London, and later in several French publications.

On 8 June 1939, the French investigative judge officially brought charges against Herschel. The proceedings against Herschel were postponed multiple times by the French authorities, despite pressure from the National Socialist government. However, soon afterwards, the pending trial was entirely eclipsed by events elsewhere. For Herschel’s parents, who had travelled on from the barracks camp in Zbąszyń to Radomsko, then on to Polish relatives in Łódź, and finally to Warsaw, the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 came as a shock.[26] Britain and France declared war against Germany on 3 September. The western campaign began on 10 May 1940. On the day Germany attacked France, Herschel was being held in the youth custody facility in Fresnes. On 12 June 1940, as the German Wehrmacht continued to advance through the country, he and 96 other prisoners were transported to Bourges in southern France under French guard. When they arrived in Bourges, they were met with chaotic scenes. The town was overfilled with refugees from the north of France. People were terrified of the German troops, who were already coming threateningly close to the town. Although he was aware that the Gestapo had their sights on the famous 17-year-old prisoner, and that they would probably have him summarily shot, the director of the prison in Bourges refused to take Herschel in. Herschel had no alternative but to continue to flee from the Germans alone on foot in the direction of Chateauroux. However, there, too, he was refused entry at the prison gates. On 10 July 1940, he finally reached Toulouse. There, on the following day, he fell into the hands of the Germans.[27]

On 14 July, he was handed over to the Gestapo and immediately taken to Berlin, where he was first held in police custody in Moabit. On 18 January 1941, he was taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was held in the “Zellenbau” isolation cells and given preferential treatment. On 16 October 1941, the German Reich pressed its own charges against Herschel, citing murder and high treason and without allowing him access to a defence lawyer. However, since the preparations for the trial did not go as planned by the National Socialist functionaries, the start of the trial was repeatedly postponed. During the unbearably long period of waiting for his trial, which was to be held in Nazi Germany and which he had no hope of winning, Herschel clearly attempted to take his own life and went on hunger strike multiple times.[28] As the planned trial date neared, his situation become significantly worse. He was kept in chains 24 hours a day. However, in the end, the trial never took place. Due to the high losses that were now being incurred by the German Wehrmacht on the eastern front and the rapid decline in support among the German population for initiating costly proceedings against Herschel, the show trial was postponed indefinitely on the orders of Adolf Hitler. Grynszpan is last mentioned in the German records in September 1942, shortly before a mass murder campaign in Sachsenhausen in which a large number of prisoners were killed. There, the trail goes cold.

[22] Armin Fuhrer, p. 13.

[23] Armin Fuhrer, p. 168.

[24] Armin Fuhrer, p. 150.

[25] Armin Fuhrer, p. 172 (translator’s translation).

[26] Armin Fuhrer, p. 236.

[27] Armin Fuhrer, p. 248 f.

[28] Armin Fuhrer, p. 258.

On survival, being forgotten and remembrance

Herschel’s sister Berta was murdered by the Nazis in Poland in 1943. His parents and his brother Markus survived the war and emigrated to Israel. Later, in 1961, his father, Sendel, gave a witness statement in the trial against the former SS Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, describing in detail the violent deportation of the Jews in 1938.[29] Herschel’s uncle Abraham, one of the 70,000 Jews delivered to Germany by the Vichy government, was murdered in Auschwitz. His aunt Chawa survived the Holocaust under unknown circumstances and returned to Paris.

Following the cancellation of the show trial, Herschel Grynszpan played no further role in the Third Reich, and was forgotten. After the war ended, no-one except his family gave any thought to the young boy who just a few years previously had caused such a surge of feeling among the general public. His relatives tried to find him, but their efforts were in vain. Herschel Grynszpan remained lost without trace, and in 1960, he was officially declared dead by the Hanover district court. Today, there are “stumbling stones” (Stolpersteine) in memory of Herschel and his sister Berta on the site in Hanover where the apartment block where the Grynszpans lived used to be. Herschel’s name is also included in the list of thousands of others engraved in the monument to the murdered Jews of Hanover on the Opernplatz in the centre of the city. Work continues on researching Herschel Grynszpan’s story and remembering his name.

Katarzyna Salski, April 2021

Literature:

Armin Fuhrer: Herschel. Das Attentat des Herschel Grynszpan am 7. November 1938 und der Beginn des Holocaust. Berlin 2013.

Dagi Knellessen: Novemberpogrome 1938. „Was unfassbar schien, ist Wirklichkeit“. Pädagogisches Zentrum des Fritz Bauer Instituts und des Jüdischen Museums (Hrsg.), Frankfurt am Main 2015.

Online:

https://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/juedische-welt/ein-attentat-mit-folgen/

https://www.dubistanders.de/Herschel-Grynszpan

https://www.dhm.de/lemo/biografie/herschel-grynszpan

[29] See Eichmann in Jerusalem, p. 207 f.