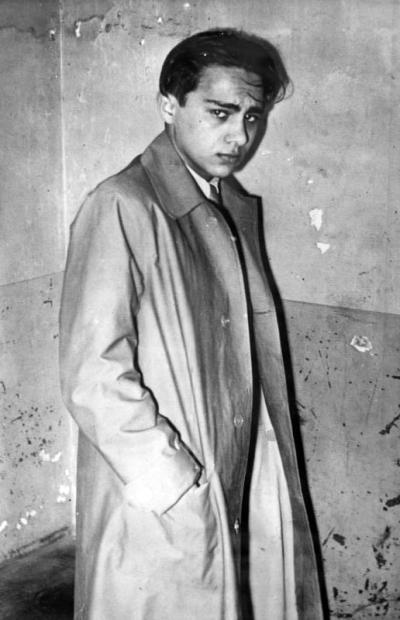

The story of Herschel Grynszpan

The Reich Pogrom Night from 9 to 10 November 1938 is rightly accorded an important and separate place in history books and in the public discourse surrounding National Socialism. It marks a turning point in National Socialist policy, in which the party’s anti-Jewish strategy suddenly shifted from the exclusion and disenfranchisement of Jews to their systematic divestment, persecution and expulsion. In the interim, a large number of historical studies have been published about the Reich Pogrom Night and the events that preceded the appalling exclusion from everyday life of fellow Jewish citizens in many parts of the German Reich. Less well known is the story of the 17-year-old Grynszpan, whose assassination of the Second Secretary at the German Embassy was used by the Nazi leadership as a pretext for the brutal violence that followed, and who tragically became a key figure in world history. Even as late as the 1980s, he was merely referred to in school textbooks as a nameless “Jewish boy”.[1] It was only during the course of more recent historical research that both the assassination itself and the motives for his actions and his family history became the focus of several less scientific analyses. He was also finally referred to by his name: Herschel Feibel Grynszpan.

Pogroms, migration and a new start in Germany

The fates and life stories of Jews in Germany and Europe are varied and tragic. They act as a warning, filling several hundred metres of bookshelves in historical archives all around the world. From antiquity to the modern era, a Christian-western enmity of Judaism became firmly established that was fed by anti-Jewish myths, nationalism and social Darwinism. In the 20th century, these attitudes would take on a hitherto unknown, horrific dimension. Just one example of the scale of European antisemitism during the 20th century is the (migration) story of the Grynszpan family, which began in 1911, in the small village of Dmenin near Radomsko, in the Russian-occupied region of Poland[2]. In addition to their financial hardship and the political tensions during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews in eastern Europe were confronted with numerous restrictions and increasing incidences of violence. For many people of the Jewish faith, the decision to emigrate from their homeland to the west in the decades that followed was first sparked by the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire in 1881. By the early 1920s, nearly three million Jews had fled eastern Europe. In 1911, the Jewish-Polish couple Ryfka (née Silberberg, *1887) and Sendel Grynszpan (*1886), who were still childless at that time, fled from Russian-controlled Poland to Germany. Like many others of the Jewish faith, they hoped to escape from poverty, as well as from the increasing number of antisemitic laws and attacks on the Jewish community. It was a hopeful new beginning.

The young couple settled in Hanover. The Prussian provincial capital had flourished as a result of the economic boom that occurred in the 19th century during the Gründerzeit period, and continued to enjoy the economic growth brought by industrialisation. While the population totalled just under 100,000 in 1874, by 1911, it had grown to over 308,000.[3] Already in 1870, the Jewish community in Hanover, which was also growing, consecrated a new, larger synagogue in Bergstrasse in the old town quarter, right next door to the main Christian churches there. The Grynszpans’ new home was one of the main economic, cultural and industrial centres in Germany, with a vibrant Jewish community.

Sendel Grynszpan earned his living as a master tailor, with his own shop in Knochenhauerstrasse 5 in the old town district of Hanover. In 1914, Ryfka’s and Sendel’s oldest child, Sophia Helena, was born. The following year, Sendel moved his tailor’s business to the neighbouring Burgstrasse 36 and the young family relocated to a modest apartment of just 40 square metres on the second floor above the shop. By 1920, this cramped space had become home to three more children[4]: Esther Beile, known as Berta (*1916), Mordechai Eliezer, known as Markus (*1919) and Salomon (*1920). Ryfka and Sendel brought their children up in the Jewish faith. They were highly respected members of the Jewish congregation and observed the traditional religious customs in their daily lives. However, at the same time, they were also open to the modern way of thinking of the western European Jews, who wanted to adapt to the culture and way of life in Germany. The Grynszpans educated their children in German and called them by German names. At home, however, the family mainly spoke Yiddish. The parents did not teach their children Polish, their language of origin.

They were certain they would never be able to return to Poland. However, suddenly and unexpectedly, the Grynszpan family, now six people in all, were granted Polish citizenship. After having being partitioned for 123 years, Poland had regained its independent statehood after the end of the First World War. The first legal regulation relating to Polish citizenship was the Polish Citizenship Act of 20 January 1920, which granted Polish citizenship not only to all those living in Polish territory, but also to people who were born in Poland and who were not eligible to become citizens of another country.[5] Since Sendel and Ryfka’s place of birth, Radomsko, was in Polish state territory, and since they had neglected to submit an application for naturalisation in Germany, they received Polish citizenship, which was also conferred on their children born in Germany.[6] Their youngest son, Herschel Feibel, known as Hermann, who was born on 28 March 1921, therefore came into the world as a Polish Jew in Germany.

[1] https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-euv/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/766/file/Fuhrer-2014-Herschel.pdf (last accessed on 24/11/2020).

[2] Following the three gradual partitions of Poland by the neighbouring powers of Prussia, Austria and Russia, Poland was divided up into three separate regions, and vanished from the map of Europe as a sovereign state from 1795 until the end of the First World War.

[3] See: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einwohnerentwicklung_von_Hannover (last accessed on 23/4/2021).

[4] Records show that Ryfka Grynszpan gave birth to seven children overall. Three of them died during birth or in infancy: no name (*/†1912), Ida (*/†1918) and Charlotte (*/†1922).

[5] https://web.archive.org/web/20140220045204/http://de.yourpoland.pl/userfiles/pdfs/ustawa-1920-de.pdf (last accessed on 23/4/2021).

[6] Armin Fuhrer, p. 28.