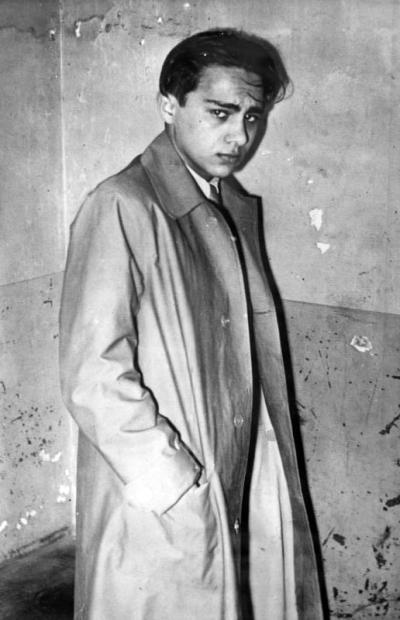

The story of Herschel Grynszpan

Economic crisis, antisemitism and an (illegal) departure for France

Herschel Grynszpan’s family were not only directly affected by the new borders that had been drawn in the wake of the First World War, but also by far reaching economic, political and personal events. Like everywhere else in the young Weimar Republic, the currency debasement that occurred between 1918 and 1923, coupled with the global economic crisis from 1929/1930, had a noticeable impact on the economy and on everyday life among the population at large in Germany. Social decline, unemployment and homelessness threatened many millions of people, and the sense of catastrophe that dominated among the population in general also brought about a change in political attitudes. The Grynszpan’s business began to struggle financially, until finally, Sendel was forced to abandon his tailor’s shop from 1930 to 1933 and open a store selling second-hand goods in Burgstrasse 19. The family lived in impoverished circumstances, and also suffered personal tragedies as well as increasing discrimination. In 1928, the oldest daughter Sophia Helena died aged about 14; in 1931, the second-youngest son, Salomon, died aged 11. When the National Socialists came to power on 30 January 1933, hatred of Jews became state doctrine. Attacks against Jewish fellow citizens in broad daylight, anti-Jewish boycotts, blockades and looting of Jewish shops were now part of the standard repertoire of National Socialist policy and those who implemented it. The second-oldest daughter Beile (Berta) felt the impact of the anti-Jewish sentiment very clearly when she was unable to find a job after passing her school leaving exams. The youngest child, Herschel, who was physically very delicate and noticeably too small for his age, left secondary school in 1935 without any qualifications and moved to the rabbinical academy in Frankfurt/Main for training in the Hebrew language. Although the rabbis and teachers attested to his great sense of justice, vivaciousness and impulsiveness, as well as his above-average intelligence and interest in politics, he did not do so well when it came to hard work, attention to detail and enthusiasm. He abandoned the training after just a few months. For the 15-year-old boy, with his Jewish faith and Polish citizenship, there appeared to be no realistic prospect of being offered either a traineeship or a job in Nazi Germany.

As a result of the increasingly aggressive antisemitism in Germany, Herschel and his family considered leaving the country. Herschel hoped to be able to emigrate to Palestine, the most important country of exile for Jewish refugees from Europe since the National Socialists came to power in 1933. In July 1936, hopeful of travelling to the “promised land” and glad to be rid of the humiliation of living under the National Socialist regime, the 15-year-old Herschel first decided to turn his back on the country alone and to travel on a Belgian visa to his uncle, Wolff Grynszpan, who lived in Brussels. There, he waited to obtain the certificate needed from the British mandate government allowing him to travel to Palestine. However, the increasingly restrictive immigration policy pursued by the British mandate government meant that Herschel, like many other Jews at that time, was denied permission to do so.[7] Since Herschel, who had no source of income, was not welcome to stay with his uncle Wolff in Brussels in the long term, he took up an invitation from his uncle Abraham and his wife Chawa, who lived in Paris, to come and live with them. In August/September 1936, Herschel illegally crossed the Belgian-French border and travelled to Paris – in contravention of the passport and outward travel regulations. This would later prove to be his downfall.

In Paris, Herschel occasionally helped his uncle Abraham out with his work, but did not take on regular employment. Although he certainly struggled with the French language, he pursued a wide range of activities typical of boys of his age. He trained at the “Aurore” Jewish sports club with friends from the local Jewish community, as well as dances in the 10th arrondissement and the Paris “demi-monde” around the Boulevard St. Martin.[8] He sent reports of his life in Paris in frequent letters to his family, who had remained in Hanover and who had originally planned to follow him to France. However, as a result of the entry bans for Jews travelling from Germany to France, all attempts by Ryfka and Sendel Grynszpan to join their son came to nothing.[9]

At the same time, the teenage Herschel found himself in the midst of a frustrating paper chase, involving application forms, official letters and games of hide and seek – as well as omissions for which he only had himself to blame. In April 1937, Herschel’s application to obtain indefinite permission to stay in France failed because he had previously entered France illegally and therefore had no stamp in his passport marking his arrival in the country.[10] The prospect of obtaining an entry visa overseas – to Palestine or the US – also remained elusive. In desperation, and against the background of the continued escalation in antisemitic violence, Herschel even wrote a letter to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt, asking him to grant him and his family asylum. However, by this time, the US had also closed its doors to Jewish refugees.[11]

On 1 April 1937 – most likely due to his own negligence in solving the problems with his passport on time – the validity of his return visa to Germany expired without his having applied for an extension. When his Polish passport also expired on 1 February 1938, Herschel approached the Polish consulate in Paris to apply for a new one, which he soon received. However, the German authorities were unwilling to issue him a new return visa to Germany on the basis of his new Polish passport. For them, Herschel officially became a foreign Jew intending to enter Germany for the first time following the expiry of his old passport and visa.[12] Why should the Germans allow him to re-enter the country when they were glad to be rid of every Jew who found themselves outside German territory? Herschel was therefore banned from entering Germany, and returning to his family. In the summer of 1938, his already difficult situation became even worse: on 8 June of that year, Herschel received an injunction from the French Ministry of the Interior requiring him to leave France by 15 August, due to the expiry of his residence permit.[13] Threatened with deportation from France, but without the possibility of returning to Germany, Herschel turned to hiding in a small attic room with relatives, never daring to leave the house during the day. Finally, on 15 October 1938, the Polish state issued a decree stating that Poles who had lived abroad for five years without interruption would lose their citizenship on 29 October. At the end of October 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, now 17 years old, became a stateless person.[14]

[7] https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/gerettete-geschichten/149158/palaestina-als-zufluchtsort-der-europaeischen-juden (last accessed on 23/3/2021); Armin Fuhrer, p. 49.

[8] Armin Fuhrer, p. 36.

[9] Armin Fuhrer, p. 37.

[10] Armin Fuhrer, p. 45.

[11] Armin Fuhrer, p. 39.

[12] Armin Fuhrer, p. 46 ff.

[13] Armin Fuhrer, p. 49.

[14] https://www.fritz-bauer-institut.de/fileadmin/editorial/download/publikationen/PM-03_Novemberpogrome-1938.pdf , p. 49 (last accessed on 24/11/2020).