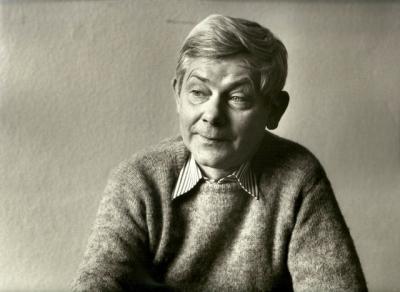

Poetry, myths, Europe: Zbigniew Herbert

During his lifetime, Zbigniew Herbert was already classed as one of the “great modern” writers of Polish literature, alongside Wisława Szymborska and Czesław Miłosz. Right up to the end of his life, he was also considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature which, unfortunately, in contrast to the other two authors, remained out of his reach. (It is largely assumed that the Socialist Polish secret police Służba Bezpieczeństwa, SB, were partly responsible for the poet and essayist not receiving this highest award.)

But Herbert was also one of the most important authors with Suhrkamp, the German publisher that publishes the “great, important, serious” literature in Germany. In 1959, just three years after it was first published in Poland, they published “Chord of light”. Heinrich Kunstmann, lecturer in Slavic studies at the Munich University, translated Herbert’s radio plays that were broadcast on German radio between 1959 and 1964. During this time, his works were also translated and published in England, in “Encounter”, “Observer” and on the BBC, to name but a few. But his breakthrough came with “Poems” in 1964 (translated into German by Karl Dedecius) and a selection of his work “Barbarzyńca w ogrodzie” as a German edition, translated by Walter Tiel, entitled “Ein Barbar in einem Garten” (Barbarian in the garden) in 1965. Herbert was brought to the attention of the new head of the publishing house, Siegfried Unseld, by the Slavist Kunstmann. Unseld was excited by Herbert’s poems and a friendship soon developed between the publisher and the poet.

In the beginning, he did not get very much money from Suhrkamp. But over time, the publisher financed Herbert’s trips and study visits, not just in West Germany but throughout Europe as well. Herbert enjoyed Mediterranean culture. His “Im Vaterland der Mythen” (In the fatherland of myths) was created especially for the German market – a literary travel guide or travel report through Greece. Herbert had always been impressed by the ancient world. He came back to these Greek myths time and again and knew how to transport them to the here and now in his verses and his prose.

The “poet between cultures“ deconstructed these myths and legends. He took away the sublime and showed it to be the excess. What remained was human. He sympathised with the minotaur. “Nike is at her most beautiful, when she hesitates,” he wrote. He always thought about those who are marginalised, forgotten. When he visited Gothic cathedrals, he appreciated their beauty, but the emotional admiration was foreign to him. Instead, he remembered the people in the stone quarries without whom these structures would not be possible, and he remembered their suffering “There is no other path to the world than the path of compassion.”

For many people, it is the splendour and grandeur in the stories of Gods and heroes from ancient times that attracts them. The German author Jan Wagner calls Herbert a “poet addicted to truth”, but that does not meant that he did not appreciate the myths and legends. He was fascinated by them because he considered the “Gods and sagas as petrified experiences of mankind”. And in this way, he found the reconciliation between these two sides of human existence, the myth and the truth.

He seems to have found his own personal reconciliation with Germany long before 1991. It is said that (West) Berlin was his favourite city. During a three-year stay there from 1967 to 1970, he was an active member of the - German-speaking - cultural scene. In 1970, he was a guest on a German talk show on the subject of “Great days? 22 June 1941 – The invasion of the Soviet Union by German troops”. He fell out with the literary critic Walter Höllerer when he defended a piece by Martin Walser. Herbert travelled through Italy, the Balkans, the Netherlands, England and Austria, which was particularly important to his career. He was also a guest lecturer at the renowned University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).