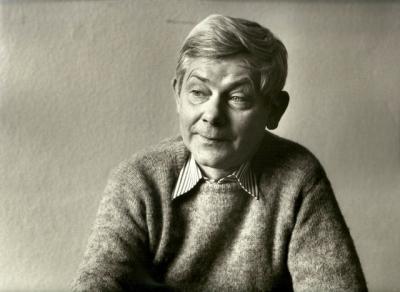

Poetry, myths, Europe: Zbigniew Herbert

Zbigniew Herbert could be called a conciliator. Not because he was a great prophet of peace, a missionary for togetherness, but because in his works he united so much contradiction or at least remoteness that you would think that it had always belonged together: ancient myths and the modern world of the 20th century, martial law in Socialist Poland and universal human values, sincerity and irony, Polish poetry and the Suhrkamp-Verlag … well, the publishing house also had some influence on the last two. Who was this Pole who ranks not just among the most important authors of this German publishing house, but among the greatest in Polish literature in recent decades?

Even before Herbert was born there on 29 October 1924, Lwów was a city which was also contradictory, troubled, cosmopolitan and, unfortunately, shaken. So the parallels with the life and work of one of its famous sons are obvious. Did this somehow dictate the path that Herbert took? When the poet was born, the town was called Lwów, because it was Polish and no longer Habsburg German. Today, it lies in the west of the Ukraine and is called Львів (Lviv). It was an important centre of Austrian, Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish life and yet was so far in the East that it was almost an outpost of Europe.

Zbigniew Herbert was still in school when Hitler and Stalin virtually divided Poland up amongst themselves. First, Eastern Poland fell under Soviet occupation in 1939, and with it Lwów. In 1941, Herbert then lived through the capturing of the city by the Wehrmacht. Despite this, he still managed to achieve his school-leaving certificate in 1943, but underground. He also completed his studies ‘underground’, studying Polish philology, and it is possible that he was also active in the Polish Home Army, Armia Krajowa or AK, of the Polish resistance. This went on until the Red Army recaptured his home town in 1944 and the Polish town was moved a little closer towards the West. Herbert’s academic career led him to Kraków and Toruń where he studied subjects, such as economics, law and philosophy. But one constant in his life remained his mistrust of politics.

The would-be saviour is not always a friend – there is a reason why Herbert’s début work “Struna Światła” (“Chord of light”) did not appear until 1956, three years after Stalin’s death. During this “thaw period”, the state censorship controlled by the Soviet government was eased. And although they were not explicitly ideological or concerned with everyday politics, Herbert’s poems aroused the suspicions of the authorities in the Socialist state. Later critics accuse the poet of having sold out to socialist realism, the state-approved from of artistic expression. And although Herbert did travel a lot, he never completely turned his back on his home country, like Czesław Miłosz, Nobel prize winner and Herbert’s friend. Others say he skilfully outplayed the censors and conveyed humanity.

What was also left over from the horrors of the war was his mistrust of Germany. Or of the Germans? In 1991, he wrote a poem for his “beloved mortal enemy“ – his translator Klaus Staemmler, authors and friends, such as Horst Bienek, Michael Krüger and Sibylle von Eicke, the publishing editor Günther Busch. The Austrian translator Oskar Jan Tauschinski is also mentioned. “The path from the trenches to the ale house was long", wrote Herbert – which is a little surprising since his international renown was due in a large part to his success and his patrons in Germany.