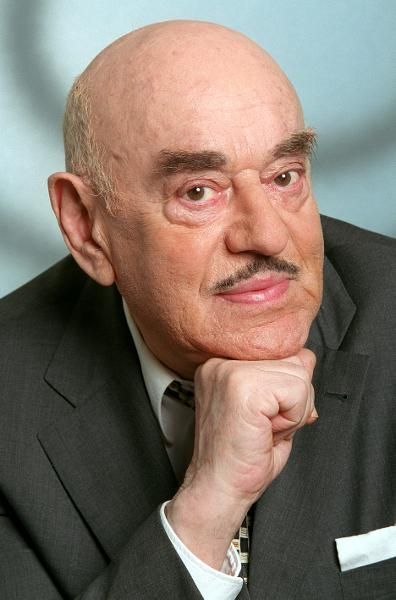

A metropolitan spirit – The theatrologist, dandy and universal scholar Andrzej Wirth (1927–2019)

If in later years you visited him in his spacious old Charlottenburg apartment in Berlin, you would come across the story of his life everywhere – in the form of global cultural history. As soon as you entered the hallway you would be confronted with a number of hand sketches, ink drawings and dedicated prints by Günter Grass, one of which (completed in 1957) was of a few dancing nuns. One year after their completion these early pictures had helped the then unknown Grass to finance his first trip from Paris, where he had written the “Tin Drum” in quasi-anonymity, back to Germany for its very first reading at a Gruppe 47 meeting. Moving along the passage to the living room, adorned with large-format drawings by Wilson, you would then come across a post-expressionist oil portrait of Wirth by the painter Edda Grossman. In front of it at the door were two Polish theatre posters: one of the Warsaw production of “The Visit”. Remarking on the Dürrenmatt translation on which he collaborated with his friend Reich-Ranicki, Wirth once said with his ironic smile and Slav-American accent: “Marcel’s German was better than mine, but my Polish was better than his!”

The second poster was for the Polish version of Peter Weiss’ “Marat/Sade”. But Wirth was not just an early translator of Weiss into Polish. This is something hardly anyone knows: when at the start, no suitable director could be found to stage its premiere in Berlin’s Schiller Theater in April 1964, Andrzej Wirth had recommended the brilliant director Konrad Swinarski from Poland, who died prematurely afterwards. His acclaimed production quickly made the “Marat/Sade” a worldwide hit.

Art and Life. Also survival. The theatre-like decorations on his father’s World War uniform were due to the fact that, as an officer in the Polish Legion with the Americans, he had liberated Italy from the Germans at the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1943/44. When his father strode through Siena in his uniform the passers-by thought he was an actor. His son Andrzej always had to laugh at this anecdote: “My father was an actor in his own way. At the beginning of the war in Poland, he escaped from a German prison camp at night, dressed as a nun!” It was precisely this episode that he was reminded of much later by the nuns dancing like peasants in Günter Grass’s drawing.

Andrzej himself always regarded his life as a “headlong flight into the future”. This was also the title of his autobiography, published in 2013, based on conversations with Thomas Irmer. He felt that migration was a life-moving, life-saving flight into the future. His lovable, self-ironic sarcasm was free of any nostalgia. For him, memories were also a way of looking back to the future. As a young polymath he had translated Lucretius and Horace from Latin into Polish, before moving on to Brecht, Grass and Frisch. For Andrzej Wirth, like Walter Benjamin and Heiner Müller, the spirits of the past were also the ghosts of the future: Lucretius was a materialist thinker, and Horace a harbinger of modern love poetry.

When Wirth spoke (less and less in German and more in his Polish-American dialect) of his distant, almost forgotten time as a young messenger for the insurgents in Warsaw 75 years before, who repeatedly survived the bullets and bombs of the occupying forces, you could feel that deep down inside him there was a pain utterly beyond his life-saving banter: a deeper scar. Along with Anatol Godfryd, the almost identically aged “artist dentist” from Berlin, who wrote about his experiences as a Jewish-Polish boy in the war in the books “Himmel in Pfützen” and “Der Himmel über Westberlin”, Andrzej Wirth was probably the last German-Polish witness to the Warsaw Uprising. He had also had first-hand experience of the Warsaw Ghetto, through whose death zone he had had to travel by tram to school.

In his final years Wirth was involved in a documentary film about himself – and wrote many so-called “short texts” of his own, some of which were epigrams, often poetic aphorisms, thought poems. These were partly in German, partly in American, and less often in Polish. He dedicated one of these lyrical reflections to Robert Wilson who owned a small apartment in Venice in addition to his Berlin apartment:

MY LAST TREE

“Where shall I plant / My last tree? // Not in Poland: // My family forest / Is cut in pieces / By three frontiers. // Not in Germany: // Hessische Wälder / Gave only shadow to my school. // And in Venice? // In Venice? // In Venice / No tree / Can produce firm roots.”

Three days before his death Andrzej emailed me the last of these legendary “short texts”, an ATW message he wanted to give to friends for a long trip. There were only two lines:

“G O T T IS

A SUPERIOR ANIMAL”.

Above it was the title: “A better world”, also in capitals. And now he himself has departed to another world.

Peter von Becker, March 2019