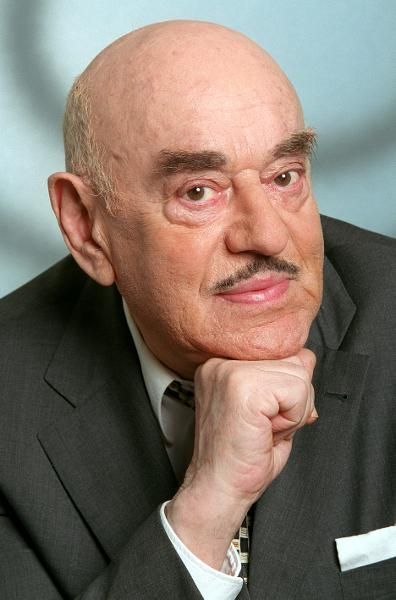

A metropolitan spirit – The theatrologist, dandy and universal scholar Andrzej Wirth (1927–2019)

My thoughts go back to the time after Andrzej Wirth died in a Berlin hospital on the evening of March 10, exactly one month before his 92nd birthday. We were friends and close neighbours in Berlin-Charlottenburg. Only a week before, he had called me with his quiet, somewhat croaky voice, that still contained a trace of his clairvoyant black humor and worldly irony. This time, however, he sounded unusually sad: “I’m in the Canaries, on Lanzarote.” I thought how wonderful, but Andrzej Wirth said: “It’s cold here. I feel alone and am going to take a plane back home.” We planned to meet again for dinner soon. But in Berlin he got a pain in his kidneys, and his American wife took him to the clinic, where he died very shortly afterwards. His circle of friends spoke of heart failure. But after Andrzej Wirth had survived a severe heart operation a few years ago, he replied to my question about his condition: “Everything’s fine. The doctors said I had no heart. That’s what women have always told me.

It was a joke. Half in pain. In his view, as an internationally famous theatre scholar, comedy and tragedy went hand in hand. It was the same with Shakespeare and Thomas Bernhard. And what about women? Andrzej was always a homme à femmes, and even (or just) when he became frail, he was accompanied to the theatre in the evenings by mostly beautiful women acting as helpful spirits, to the delight of the highly attractive, highly alert intellectual.

At the end of his long journey through world history, which was to some extent a sort of stage performance, he did indeed need some help in order to be able to walk – whether on the arms of younger ladies and supported by his smart silver pommel, or simply on his own behind his rollator, an amazingly chic gadget that seemed to mirror its owner who turned it into a kind of pedestrian Bentley. After the death of the flamboyant cultural sociologist and writer Nicolaus Sombart, Andrzej Wirth was Berlin’s last dandy.

A second Wirth joke, also a combination of jest and pain, also fits this. If you came across your old friend in a café, on the market square or in the theatre, wearing – in addition to the above-mentioned accessories – a fluttering white silk scarf, turned-up shirt collars, red golf shoes or black-and-white gigolo shoes as if he were in a Hollywood nostalgia movie, and asked him how he was doing, he would gladly answer with an anecdote from his former homeland: “A Jewish merchant is attacked and stabbed by robbers in a forest in Poland. When they find him and want to know whether his wounds hurt his chest and abdomen, the robbed Jew replies: “Only if I laugh.”

This punch line can also be found in George Tabori’s Jewish-Christian-universal Easter comedy “Goldberg Variations”, in which Jesus, questioned on the cross after the lance thrust by the Roman legionnaire about his pain, gives the same answer. “Only if I laugh”. Andrzej Wirth, of course, told us the source. Talking to this highly shrewd mind, you always got a glimpse of the cultural and historical background.

Born on a country estate in Włodawa 1927 in the border triangle between eastern Poland, Belarus and Ukraine, (near the later Nazi extermination camp Sobibor), in the summer of 1944 the young Andrzej had taken part in the Warsaw Uprising against the German occupying forces at the age of 17: and he later survived Stalinism. After the war he studied philosophy and literature in Warsaw and received his doctorate for a thesis on Brecht. In 1956–58 at the invitation of the Berliner Ensemble he lived in East Berlin for a while as a guest student and dramaturgical consultant, before returning to Warsaw. One of his friends was Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who was several years older. With him Wirth translated Kafka’s “The Castle”, Dürrenmatt’s “The Visit”, and early works by Günter Grass and Max Frisch from German into Polish.

In the thaw after Stalin’s death he was editor of the legendary magazines “Polityka” and “Nowa Kultura”. Andrzej Wirth escaped a new Stalinist ice age in the 1960s with a scholarship to the West. There he was a visiting professor for literature, cultural history and theatre primarily in the USA, in Amherst, New York, Stanford and (on the recommendation of Walter Höllerer) at the Berlin Technical University. Between these, or later, came Oxford and the Free University in Berlin. In addition, thanks to his connections with Grass und Frisch, Wirth soon belonged to Group 47, whose 1966 meeting in Princeton abroad he helped to organize. This meeting featured Peter Handke’s sensational first revolutionary appearance. Andrzej Wirth quickly understood his self-reflexive debut piece “Publikumsbeschimpfung” (“Insulting the Audience”), in which Handke had installed a speaking choir instead of individual characters, as an example of avant lettre, “post-dramatic” theatre that he himself would later declare to be the definitive method (and sometimes fashion) of modernism.

An utterly different leap: When Volker Schlöndorff’s “Return to Montauk” premiered at the 2017 Berlinale and we were talking about the film that was modelled on Max Frisch's famous novella “Montauk”, Wirth told me that he was the man behind the whole story: “The love story in May 1974, described by Max Frisch, was based on the affair with my student Alice, who became Lynn in the book. I was holding a seminar in New York on contemporary German literature, when I heard that Max was coming to do some readings. So I invited him to attend my seminar, and Alice took care of him on behalf of his New York publishing house. That’s how it was. Love happens.”

Wirth was indeed a great mediator, a real cosmopolitan, a Polish-American-German professor with connections stretching from Venice in Italy to Venice in California. In this respect, he can only be compared with his compatriot Jan Kott, who died in Santa Monica in 2001: a Pole in exile whose books taught the whole world to understand Shakespeare anew. For his part, Wirth brought the Polish (theatre) avant-garde from Witkiewicz and Gombrowicz to Jerzy Grotowski with him to the West. His interpretation of the work of his American friend Robert Wilson helped him on his way to world fame: for example, in 1979, during the legendary performance of “Death, Destruction & Detroit”, in the Berlin Schaubühne he unraveled the secret of the scenes that oscillated between the prison and the world of machines and explained them as Wilson’s parable about the Hitler intimus Albert Speer. For Germans he discovered, among many others, the grandiose Jewish-Galician poet Bruno Schulz, a long forgotten victim of Nazi terror.

This man with his white crew cut and dark glasses to protext him from the light that in his later years was often too bright for him, was a leading metropolitan spirit. At his famous house parties young ladies occasionally appeared dressed in his father’s impeccable officer’s uniform that was so full of military decorations that it resembled a theatrical costume. This clearly shows that the dandy Andrzej Wirth was not a man to be found in ordinary salons. He also had a sense for the playful in everyday life, for its subtext and deeper content – and also for the cosmopolitan dialogue of cultures. That’s why a young (female) general in a Polish war uniform in Wirth’s living room could transform herself into a delicate Japanese Butoh dancer. Such an event might be followed by a presentation by a Venetian fashion designer or a brief talk by a New York professor of aesthetics, both of whom were women.

After his return from the USA, however, he became famous and, according to his own self-ironic assessment, somewhat notorious as the founder of the Institute for Applied Theatre Studies at the University of Giessen. Starting in 1982, it also turned German theatre studies upside down from theory into practice, following the example of the drama departments in US American universities. Indeed, with Wirth’s avant-garde blessing, the Institute soon became the Central European breeding ground of that “post-dramatic” theatre, which regards literary plays as little more than deconstructable “material” for any performative style: the splendour and misery of the contemporary scene. The Institute for Applied Theatre Studies, in short ATW like its creator (Andrzej Tadeusz Wirth), then turned out “best of the bunch” directors and authors like René Pollesch, Tim Staffel, Hans-Werner Kroesinger, the playwright (and thus anti-post-dramatist) Moritz Rinke and the heads of the groups Rimini Protokoll, She She Pop and Gob Squat. And it was Wirth who, between 1982 and 1992, brought artists and intellectuals like Robert Wilson, Heiner Müller, George Tabori and Marina Abramovic to give workshops and courses in the otherwise peaceful Hessian province.

If in later years you visited him in his spacious old Charlottenburg apartment in Berlin, you would come across the story of his life everywhere – in the form of global cultural history. As soon as you entered the hallway you would be confronted with a number of hand sketches, ink drawings and dedicated prints by Günter Grass, one of which (completed in 1957) was of a few dancing nuns. One year after their completion these early pictures had helped the then unknown Grass to finance his first trip from Paris, where he had written the “Tin Drum” in quasi-anonymity, back to Germany for its very first reading at a Gruppe 47 meeting. Moving along the passage to the living room, adorned with large-format drawings by Wilson, you would then come across a post-expressionist oil portrait of Wirth by the painter Edda Grossman. In front of it at the door were two Polish theatre posters: one of the Warsaw production of “The Visit”. Remarking on the Dürrenmatt translation on which he collaborated with his friend Reich-Ranicki, Wirth once said with his ironic smile and Slav-American accent: “Marcel’s German was better than mine, but my Polish was better than his!”

The second poster was for the Polish version of Peter Weiss’ “Marat/Sade”. But Wirth was not just an early translator of Weiss into Polish. This is something hardly anyone knows: when at the start, no suitable director could be found to stage its premiere in Berlin’s Schiller Theater in April 1964, Andrzej Wirth had recommended the brilliant director Konrad Swinarski from Poland, who died prematurely afterwards. His acclaimed production quickly made the “Marat/Sade” a worldwide hit.

Art and Life. Also survival. The theatre-like decorations on his father’s World War uniform were due to the fact that, as an officer in the Polish Legion with the Americans, he had liberated Italy from the Germans at the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1943/44. When his father strode through Siena in his uniform the passers-by thought he was an actor. His son Andrzej always had to laugh at this anecdote: “My father was an actor in his own way. At the beginning of the war in Poland, he escaped from a German prison camp at night, dressed as a nun!” It was precisely this episode that he was reminded of much later by the nuns dancing like peasants in Günter Grass’s drawing.

Andrzej himself always regarded his life as a “headlong flight into the future”. This was also the title of his autobiography, published in 2013, based on conversations with Thomas Irmer. He felt that migration was a life-moving, life-saving flight into the future. His lovable, self-ironic sarcasm was free of any nostalgia. For him, memories were also a way of looking back to the future. As a young polymath he had translated Lucretius and Horace from Latin into Polish, before moving on to Brecht, Grass and Frisch. For Andrzej Wirth, like Walter Benjamin and Heiner Müller, the spirits of the past were also the ghosts of the future: Lucretius was a materialist thinker, and Horace a harbinger of modern love poetry.

When Wirth spoke (less and less in German and more in his Polish-American dialect) of his distant, almost forgotten time as a young messenger for the insurgents in Warsaw 75 years before, who repeatedly survived the bullets and bombs of the occupying forces, you could feel that deep down inside him there was a pain utterly beyond his life-saving banter: a deeper scar. Along with Anatol Godfryd, the almost identically aged “artist dentist” from Berlin, who wrote about his experiences as a Jewish-Polish boy in the war in the books “Himmel in Pfützen” and “Der Himmel über Westberlin”, Andrzej Wirth was probably the last German-Polish witness to the Warsaw Uprising. He had also had first-hand experience of the Warsaw Ghetto, through whose death zone he had had to travel by tram to school.

In his final years Wirth was involved in a documentary film about himself – and wrote many so-called “short texts” of his own, some of which were epigrams, often poetic aphorisms, thought poems. These were partly in German, partly in American, and less often in Polish. He dedicated one of these lyrical reflections to Robert Wilson who owned a small apartment in Venice in addition to his Berlin apartment:

MY LAST TREE

“Where shall I plant / My last tree? // Not in Poland: // My family forest / Is cut in pieces / By three frontiers. // Not in Germany: // Hessische Wälder / Gave only shadow to my school. // And in Venice? // In Venice? // In Venice / No tree / Can produce firm roots.”

Three days before his death Andrzej emailed me the last of these legendary “short texts”, an ATW message he wanted to give to friends for a long trip. There were only two lines:

“G O T T IS

A SUPERIOR ANIMAL”.

Above it was the title: “A better world”, also in capitals. And now he himself has departed to another world.

Peter von Becker, March 2019