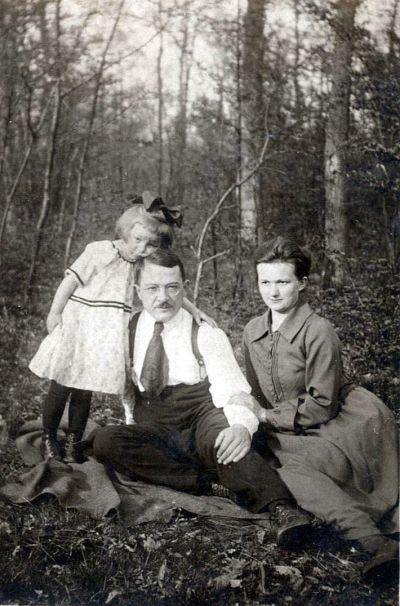

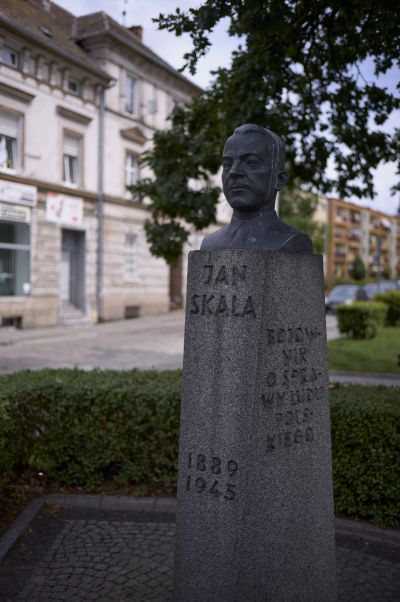

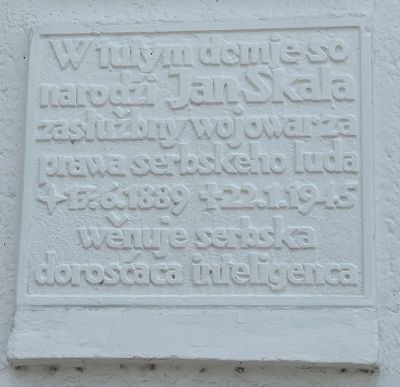

Jan Skala (1889–1945). A close Sorbian associate of the Union of Poles in Germany

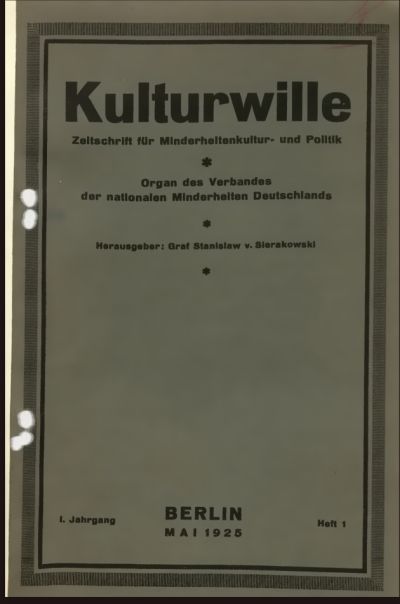

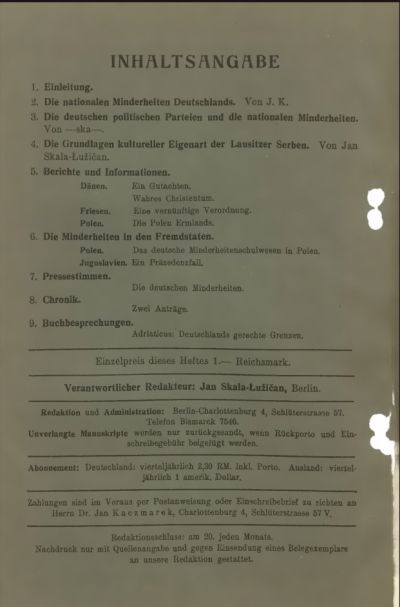

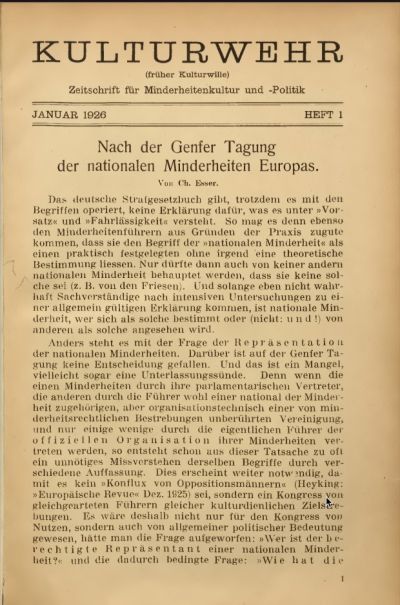

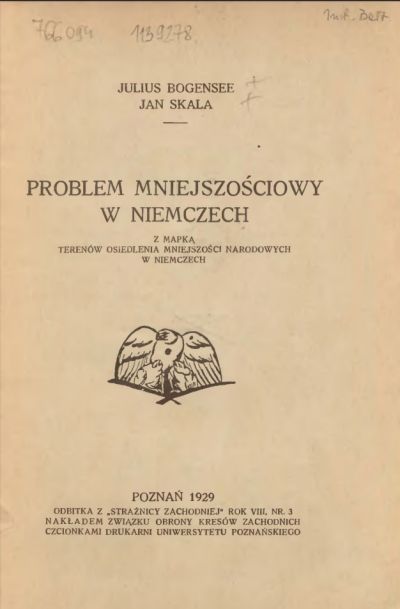

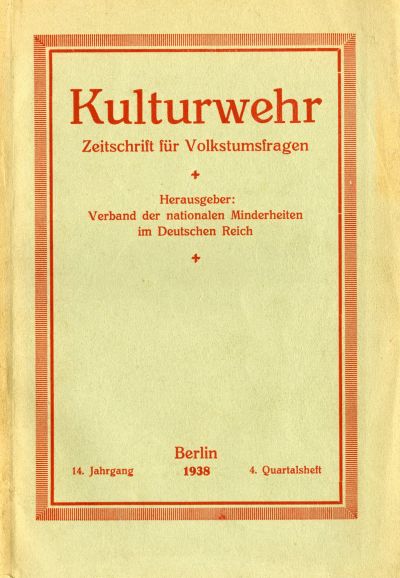

From the start, he cooperated with the Union of Poles in Germany, which at that time was the most powerful organisation representing the largest national minority in Germany. He became friends with leading Polish functionaries. At the same time, he grew increasingly active in promoting the interests of other national minorities in Germany. In May 1925, he took over the editorship of the Berlin-based magazine “Kulturwille” (from January 1926: “Kulturwehr”), the mouthpiece of the Association of National Minorities in Germany (Verband der nationalen Minderheiten in Deutschland). During the 1930s, Skala was vice-president of the organisation. The magazine soon became an important forum for discussing experiences between minorities, particularly Poles, Danes, Frisians, Lithuanians and Sorbs. In 1929, in collaboration with the Dane Julius Bogensee, he published a study on national minorities and their legal situation in Germany (in Polish and German). The study was met with a great deal of interest, including outside Germany. In 1925 and 1927, Skala took part in meetings of national minorities in Geneva. In 1932, he was the only Sorbian candidate to be put up for election to the Prussian and German parliament. Although he lost the vote, his popularity increased. He was a good speaker, and was easily able to make new contacts during his frequent travels.

After the seizure of power by the National Socialists in Germany in 1933 and the introduction of restrictions on the activities of national minorities, the importance of the “Kulturwehr” magazine increased even further. Skala used the magazine forum to provide information about discriminatory practices, and published detailed articles and reports. In this way, he criticised the racial and nationalities policy of the Nazis in relation to the national minorities and other ethnic groups in Germany. He also worked on a collection of data about the Polish minority, which were included in the “The Lexicon of Polish life in Germany”. Such activity, although it remained within the bounds of what was legally possible, required a great deal of civic courage – something that Skala did not lack. He was harassed by the government in a variety of different ways; his apartment was searched and he was monitored by the police. Finally, in 1936, his name was struck off the list of authorised editors by the Reich Chamber of Culture (Reichskulturkammer), and he was forced to resign. He was prohibited from working as a journalist, and was forced to seek other ways of earning a living.

Even so, despite the increasing risk, Skala refused to stop his work in the political and social arena. He moved to Bautzen and continued his activities for the Union of Poles in Germany and “Domowina”, the association of Sorbs in the Lusatia region (Bund Lausitzer Sorben e.V.). In January 1938, he was arrested and accused of “Preparatory activities for high treason”. He was imprisoned in Dresden until October of that year. After his release, he continued to be monitored by the police. During this time, his health deteriorated further. During the final years of his life, he battled illness, financial difficulties, and various forms of persecution by the state. For a long time, he was unable to find permanent employment, and his wife was also dismissed from her job. In 1941, he moved to Berlin, where he was employed by a statistics publishing house. He suffered a great tragedy when his only son died on the eastern front in 1943. In 1943/1944, as the bombing of Berlin intensified, he moved to the village of Dziedzice (Erbenfeld), where his wife’s family lived, near the town of Namysłów (Namslau). In the village, the local Polish population lived side by side with the Germans. After several months, he found work in an office in one of the industrial enterprises in Namysłów. Several times during this period, he helped Poles working in the resistance.