Jan Skala (1889–1945). A close Sorbian associate of the Union of Poles in Germany

Jan Skala was born on 17 June 1889 in the village of Nebelschütz (Njebjelčicy) in eastern Saxony. His father, Jakub Skala, worked in the stone quarries there. His mother, Maria, was a homemaker who earned a living as a seamstress. The couple had six children (Jan was the third child). Although the family did not have much money, his parents decided to enable Jan to have an education. After moving to the neighbouring town of Panschwitz (Pančic), he first attended the local high school before spending a year at the Catholic teaching seminary in Bautzen (Budyšin). However, due to his family’s lack of funds, he was forced to give up his education. He then learned a trade as a ceramicist and porcelain painter. In the years that followed, he worked in different ceramics factories in Germany and Bohemia. During this time, he developed an interest in social democratic ideas and the Sorbian movement.

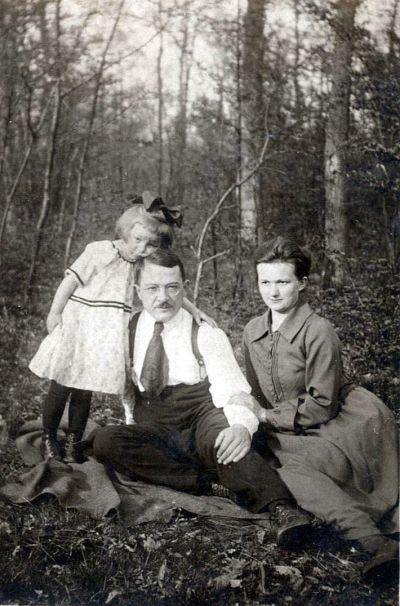

He also did not give up on his desire to continue with his education, and regularly attended evening courses. Even before the First World War, he was already making his debut as a social democratic publicist and poet (he published his first volume of poems several years later, in 1920). From 1916 onwards, Jan Skala fought in the First World War. He fought with the German Army on several fronts, while at the same time attending a course for translators. Over the following years, he improved his knowledge of multiple Slavic languages. During the war, he wrote several reports, none of which were written in the style typical for the propaganda of the time, which depicted military campaigns with enthusiastic reverence. In 1917, he married a woman from Berlin, Else Maria Lachmann, with whom he had three children: two daughters and a son. After the war and the revolution, he briefly became a member of a paramilitary unit in Berlin which supported the police during the period of unrest in Germany. However, as early as 1919, he decided to return to the Lusatia region, where he actively participated in politics and society. He was a co-founder of the Lusatian People’s Party (Lausitzer Volkspartei) and published their newspaper “Serbski Dźenik” (“Sorbian Daily”). The Volkspartei strove to promote a peaceful coexistence between Germans and Sorbs, while preserving the rights of minorities (Skala was a member of the party’s executive committee until 1933). At the same time, he also wrote articles in the newspaper about the problems facing Germany’s national minorities.

At the beginning of 1921, he began a collaboration in Bautzen with the “Serbske Nowiny” (“Sorb News”) newspaper, although he soon abandoned the project due to political differences. After he left Bautzen, he went to Prague, where he found employment as an editor at the “Prager Presse” (“Prague Press”), a Czechoslovakian German-language government newspaper. In 1922, while he was living in Prague, he published a political agenda for the Sorbs: “Wo serbskich prašenjach” (“On Sorbian Issues”). He postulated the economic stability of the Sorbian lands as a guarantee for the maintenance of the Sorbian language and identity, which had been weakened due to migration to the cities in the search of better living conditions. Throughout his life, he remained a loyal German citizen, and resisted the demands for a separation of the Lusatia region and its incorporation into the Czechoslovakian state (as, for example, some politicians from the region called for in 1919). The political elite in Prague did not approve of his clear stance on this issue. He therefore decided to move to Berlin to continue his political, organisational, and journalistic work for the Sorbian minority.

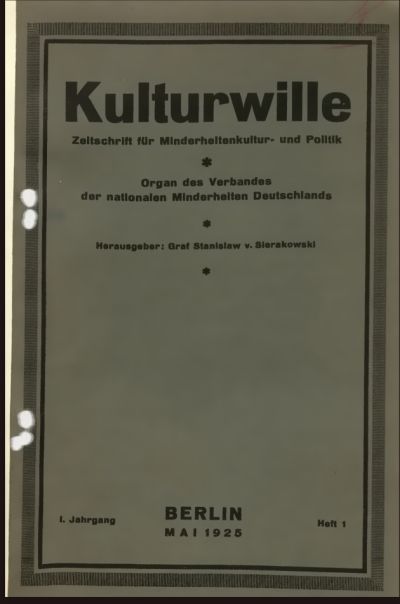

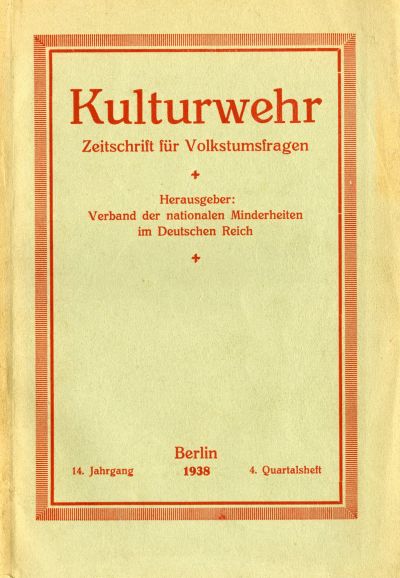

From the start, he cooperated with the Union of Poles in Germany, which at that time was the most powerful organisation representing the largest national minority in Germany. He became friends with leading Polish functionaries. At the same time, he grew increasingly active in promoting the interests of other national minorities in Germany. In May 1925, he took over the editorship of the Berlin-based magazine “Kulturwille” (from January 1926: “Kulturwehr”), the mouthpiece of the Association of National Minorities in Germany (Verband der nationalen Minderheiten in Deutschland). During the 1930s, Skala was vice-president of the organisation. The magazine soon became an important forum for discussing experiences between minorities, particularly Poles, Danes, Frisians, Lithuanians and Sorbs. In 1929, in collaboration with the Dane Julius Bogensee, he published a study on national minorities and their legal situation in Germany (in Polish and German). The study was met with a great deal of interest, including outside Germany. In 1925 and 1927, Skala took part in meetings of national minorities in Geneva. In 1932, he was the only Sorbian candidate to be put up for election to the Prussian and German parliament. Although he lost the vote, his popularity increased. He was a good speaker, and was easily able to make new contacts during his frequent travels.

After the seizure of power by the National Socialists in Germany in 1933 and the introduction of restrictions on the activities of national minorities, the importance of the “Kulturwehr” magazine increased even further. Skala used the magazine forum to provide information about discriminatory practices, and published detailed articles and reports. In this way, he criticised the racial and nationalities policy of the Nazis in relation to the national minorities and other ethnic groups in Germany. He also worked on a collection of data about the Polish minority, which were included in the “The Lexicon of Polish life in Germany”. Such activity, although it remained within the bounds of what was legally possible, required a great deal of civic courage – something that Skala did not lack. He was harassed by the government in a variety of different ways; his apartment was searched and he was monitored by the police. Finally, in 1936, his name was struck off the list of authorised editors by the Reich Chamber of Culture (Reichskulturkammer), and he was forced to resign. He was prohibited from working as a journalist, and was forced to seek other ways of earning a living.

Even so, despite the increasing risk, Skala refused to stop his work in the political and social arena. He moved to Bautzen and continued his activities for the Union of Poles in Germany and “Domowina”, the association of Sorbs in the Lusatia region (Bund Lausitzer Sorben e.V.). In January 1938, he was arrested and accused of “Preparatory activities for high treason”. He was imprisoned in Dresden until October of that year. After his release, he continued to be monitored by the police. During this time, his health deteriorated further. During the final years of his life, he battled illness, financial difficulties, and various forms of persecution by the state. For a long time, he was unable to find permanent employment, and his wife was also dismissed from her job. In 1941, he moved to Berlin, where he was employed by a statistics publishing house. He suffered a great tragedy when his only son died on the eastern front in 1943. In 1943/1944, as the bombing of Berlin intensified, he moved to the village of Dziedzice (Erbenfeld), where his wife’s family lived, near the town of Namysłów (Namslau). In the village, the local Polish population lived side by side with the Germans. After several months, he found work in an office in one of the industrial enterprises in Namysłów. Several times during this period, he helped Poles working in the resistance.

Jan Skala did not survive the fall of the Third Reich. Shortly before the fighting on the front reached the village, it was evacuated by the Nazis. However, Skala and several other villages chose to remain. On 22 January 1945, he was shot while attempting to protect his family and his neighbours from the Soviet soldiers who had occupied the village. He was buried in a mass grave in the cemetery in the neighbouring village of Włochy (Wallendorf) together with several others who were killed. His wife and daughter left Dziedzice for Germany at the end of 1945.

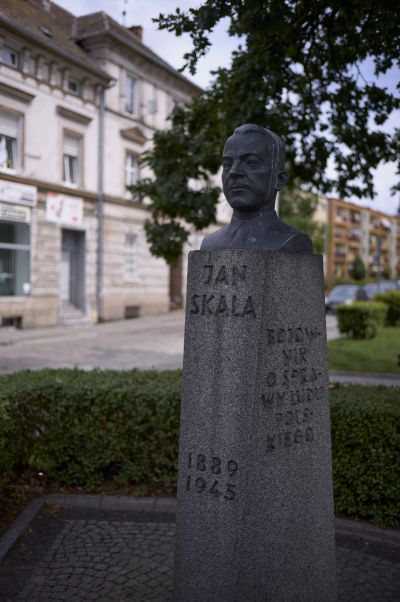

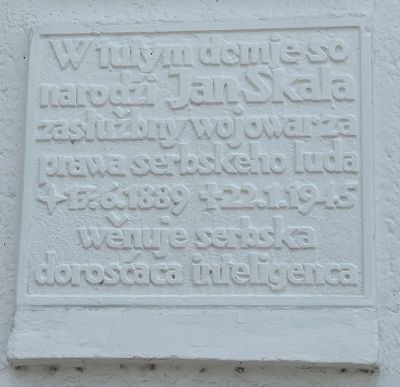

Thanks to the efforts of the Friends of Namysłów Homeland association (Verein der Namslauer Heimatfreunde) and the “Domowina” association of Lusatian Sorbs, Jan Skala has not been forgotten. In 1965, a bust of Skala by the Bautzen-based sculptor Rudolf Enderlein was unveiled in Namysłów, and the square on which it stands is also named after him. Thanks to the cooperation between the two organisations, a symbolic gravestone was erected in his honour at the cemetery in Włochy (his body has not yet been exhumed). In 2009, to mark the 120th birthday of Jan Skala, an academic conference, “Jan Skala (1889-1945) national activist, publicist and artist”, was held, and in Włochy, an information panel was attached to a column on the cemetery gate bearing the following words:

“Here lies Jan Skala, Sorbian national activist, publicist, politician, advocate of Polish-Sorbian cooperation, poet and prose writer.

Jan Skala was born on 17 June 1889 in Nebelschütz (Sorb. Njebjelčicy) in the Upper Lusatia region. In 1919, he was a co-founder of the Lusatian People’s Party. He was the editor of the “Sorbian Daily” (Sorb. “Serbski Dźenik”), “Sorbian News” (Sorb. “Serbske Nowiny”) and the “Prager Presse”. From 1925 to 1936, he was editor-in-chief of the theoretical-ideological organ of the Association of National Minorities in Germany, which first appeared under the title “Kulturwille” and later “Kulturwehr”. During this time, he helped create the ideological platform of this organisation, actively participated in the conferences of the European national minorities in Geneva, and worked in close cooperation with the Union of Poles in Germany. He made his debut as a writer in 1910 in the “Lausitz” (Sorb. “Łužica”) newspaper. In 1920, he published a volume of poems entitled “Crumbs” (Sorb. “Srjódki”). In 1923, a further volume of poems was published entitled “Sparks” (Sorb. “Škrě”). He also wrote the novella “The Old Šymko” (Sorb. “Stary Šymko”). This work was published for the first time in Polish translation in 1936. From 1933 onwards, he was the subject of intensified observation by the German authorities, who in 1936 withdrew his authorisation to work as a journalist. In 1938, he was arrested and spent eight months in a Nazi prison. In 1944, he moved to Erbenfeld (today: Dziedzice), and took up employment in Namslau (today: Namysłów). During this time, he made contact with the Home Army structures which operated in the Namysłów region. Tragically, he was killed at the hands of a soldier of the Red Army on 22 January 1945.

The memorial plaque was donated by the people of the community of Domaszowice Dziedzice in honour of the poet’s 120th birthday on 27 May 2009”.

Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, July 2023

Selected bibliography:

Dan Gawrecki: Jan Skala a Czesi. Przyczynek do biografii, https://www.prolusatia.pl/ksiaznica/artykuly/244-jan-skala-a-czesi-przyczynek-do-biografii.html (letzter Zugriff: 2.08.2023);

Leszek Kuberski: Zarys biografii politycznej, Opole 1993;

Michael Nuck: Jan Skala (Johann Skala), https://saebi.isgv.de/biografie/Johann_Skala_(1889-1945) (last accessed on 2.08.2023);

Dietrich Scholze-Šołta: Śmierć na Dolnym Śląsku. Tragizm serbołużyckiego pisarza Jana Skali (1889-1945), https://www.prolusatia.pl/ksiaznica/artykuly/245-mier-na-dolnym-lsku-tragizm-serbouyckiego-pisarza-jana-skali-1889-1945.html (last accessed on 2.08.2023).