Wanda Landowska

“A stir runs through the room; a dark haired, sharp featured, friendly-looking young lady appears, as lithe as Salome and as elegant as a marquess. She is the fairy godmother of early piano music, equally popular in Moscow, Berlin and Paris. A Polish citizen by birth, like many of her important compatriots she soon turned her back on her fatherland. For every artist it is good and healthy to nourish a great yearning. Poles do so by emigrating; they thereby develop a constant yearning for Poland for the rest of their lives. This was the case with Chopin, Paderewski, and also Wanda Landowska: as the interesting young lady was called.”

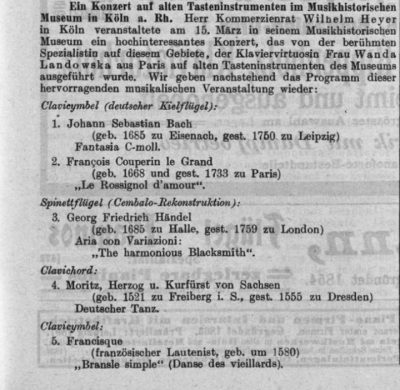

The Leipzig Zeitschrift für Instrumentenbau quoted from a report in the Kölnischen Zeitung, about a concert on early keyboard instruments in the Music History Museum of the Cologne sponsored by the entrepreneur Wilhelm Heyer and given on 15th March 1911. (see PDF) The audience heard music from the Renaissance, the baroque era and the romantic period, featuring compositions by Duke Moritz of Saxony (1521-1555), Couperin, Bach, Händel and Schubert on an 18th century “clavicymbel”, harpsichord and clavichord, on a fortepiano made in 1830 and a large three-manual spinet made in 1909 by the Leipzig instrument-maker Hermann Seyffarth. The only soloist of the evening was Wanda Landowska. When she was still quite young she had developed an interest for early music and historical keyboard instruments. Convinced that their sound, and not that of contemporary grand pianos, would provide the key to understanding the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, from 1903 onwards she only gave recitals on newly made harpsichords constructed by the Paris firm Pleyel & Cie, which specialised in pianos and harps whose sound and its effect on the listeners at first failed to impress her.

The Kölnische Zeitung continued: “Equipped with an unusual intelligence, she has discovered her own very personal field of activity in harpsichord playing, and is now transferring her established taste onto the music of early masters. […] And in doing so she has not only reshaped traditional music, but strived to reach its ideal perfection once again. That is her secret and her art. She has acquainted herself with keyboard mechanisms and practised with great patience and discipline until her fingers have been able to revive the ancient art of playing as it was in full force 200 years ago. And now she is exploring this fine old art on early instruments, and reproducing sounds that are certainly deceptively similar to those conceived by the early masters.” The Zeitschrift für Instrumentenbau summarised her recital in the Music History Museum[1] as follows: “The effect on the compositions played on the instruments made by Kirkman, Lemme and Streicher was truly astonishing, whereas reproducing Händel and Bach on the Silbermann clavicymbel and the newly-made Seyffarth spinett was a wondrous experience. The Moonlight Sonata, an encore on Streicher’s fortepiano, had an incomparable appeal. The way in which Landowska performed it on the old keyboard instrument, had never before been heard.”

That said, it needed another two recitals before Landowska was able to realise her “ambitious, mushrooming, constant dream” of making audible the sound of early baroque instruments (until then they had only been kept in museums) on a newly made harpsichord, and was able to experience the triumphant success of her long-standing “campaign… to create an instrument that was as similar as possible to that played by Bach”[2]. In September 1911, at the so-called Kleines Bachfest in Eisenach organised by the New Bach Society, a number of works were played consecutively on the modern grand piano and a harpsichord in order to be able to compare the two. The Zeitschrift der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft reported: “To confirm the true result of this competition: the harpsichord was the instrument that enjoyed … a supreme success… However, in the interest of modern pianos, it would have been valuable to have been able to compare somewhat more spirited representatives of this instrument with the brilliant representative of the harpsichord, Frau Wanda Landowska.”

It was not until the VI. Deutsches Bachfest (presented by the Neuen Bachgesellschaft between the 15th and 17th June 1912 in Breslau) that Landowska was able to publicly present and play the “Grand Modèle de Concert” harpsichord she had herself conceived, and that had been constructed by the Pleyel company. In order to raise the dynamics and the shaping of the sound, the instrument was equipped with seven pedals, a lute, one 16-foot register, two 8-foot registers and a 4-foot register, all within an iron frame that enabled it to be toured for recitals. Henceforth Landowska propagated it all over the world. The Zeitschrift der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft wrote: “The artist set in motion every feature of her instrument and her intrinsic intelligence and even mediated a whole range of new impressions to her contemporary specialists: the Prelude and Fuge in b flat minor stood out amongst many. On a modern piano it is impossible to attain the clarity and transparency of the texture of the fugue we heard in her planned use of the 16 foot and 4 foot registers, not forgetting other finely detailed effects that are quintessential to the harpsichord.” In 1913 Landowska was appointed head of a harpsichord department specially created for her, at the Royal Academy of Music in Charlottenburg, where she also used the new Pleyel harpsichord. (Fig. )

She was trained in Romantic piano music by her Warsaw teachers, the Chopin specialists Jan Kleczyński (1837-1895) and Aleksander Michałowski (1851-1938); nonetheless from the very start her real love was the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Even during her studies in Berlin under Heinrich Urban (composition) and Moritz Moszkowski (piano) Bach’s “Well Tempered Clavier“ remained in the forefront of her interest. She composed songs, works for strings and piano pieces that were also printed and which her mother in Warsaw sent to the Norwegian composer Edward Grieg to ask for his opinion[3]. At her recitals Wanda played her own compositions, works by Bach and late Romantic piano pieces. In Berlin she came in touch for the first time with the (then still playable) “Clavicymbel von Bach”[4] in the Royal Collection of Early Music Instruments.

In 1899 she made her debut at the Leipzig Gewandhaus concerts with one of the three piano parts in Bach’s D minor concerto for three pianos and strings. In September that year in Warsaw she made the acquaintance of the journalist, actor and ethnologist Henri Lew (1874-1919), who was five years older than she. She decided to continue her career as a composer in Paris, where she married Lew in the following year. Her interest in early music inspired her to join the circle of musicians in Schola Cantorum that had been set up in 1896. The theologian, organist and Bach researcher Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965), who was later to become a missionary doctor and founder of the Lambarene jungle hospital, was also a part of this group. The two kept up an intensive exchange of ideas and opinions on how to interpret Bach’s works.

She began to give recitals on the harpsichord in 1903. With the support of Henri Lew, she studied original sources from the 16th to the 18th century in order to reconstruct fingering, registers, temporal and decorative elements. She also collaborated with the Pleyel firm whose harpsichords she promoted from then on. As time went by her activities as a composer fell into the background. Instead she undertook concert tours of Great Britain, Germany, Switzerland, before returning to Paris and finally in 1907 travelling to Moscow where played at a reception from Russian artists in the Salle Pleyel and met Leo Tolstoy for the first time. In November that year she took her harpsichord to Tolstoy’s house, Yasnaya Polyana (see PDF; Fig.). She visited him once again in 1909, following which she gave recitals in St Petersburg and Moscow. In the same year a 270 page book she had written with Henri Lew-Landowski was published in Paris: it was called “Musique ancienne. Style - Interprétation - Instruments - Artistes”. In 1910 she played at a Bach Festival in Duisburg.

That said, Landowska’s status in the music world was in no way uncontested. Whilst she was in Paris her decision to revive harpsichord music had been received sceptically, because previous attempts to do so had failed on account of the poor quality of the instruments. In her biography she wrote that anyone who heard her as a pianist was worried that she might “neglect the piano in favour of the ‘old joanna’.”[5] And one year after taking up a post at the Music Academy in Charlottenburg, in May 1914 she felt forced to defend herself with an article in the Vossischen Zeitung entitled “The Renaissance of the Harpsichord”; for “it is true that the harpsichord still has many stubborn opponents, but most of these consist of piano teachers and old-style virtuosi”.[6]

When war broke out, Wanda Landowska suddenly found herself classed as an enemy of the state in Germany because she had been born under Russian dominance. Two weeks after the German declaration of war on Russia she was the subject of an insulting article in the Berliner Tageblatt that called her a “Russian subject … at the Royal Academy of Music”. Four days later she answered in a reader’s letter “that I am not Russian. Quite the contrary – I am a Pole. Whilst the German hatred of the Russian government is scarcely two weeks old, our mutual hatred has lasted for at least a century”. (see PDF) The situation appeared to become more normal after the Leipzig Journal Signale für die musikalische Welt and the Tägliche Rundschau spoke out in defence of Landowska and other foreign teachers at the Academy[7].

During the war years Landowska and her husband had a stately residence in the Berlin suburb of Wilmersdorf, in which recitals were followed by a dinner for those present. Rainer Maria Rilke and Gerhart Hauptmann were just two of the guests. Ten years later in the Vossischen Zeitung Lotte Zavrel still spoke of the indescribable dishes, glorious old china tableware, oriental and Spanish dancers and a Landowska, who tirelessly played tangos on her Boston. (see PDF) Everything ended in catastrophe in April 1990. After right-wing groups accused Landowska and her husband of Bolshevik activities Henri Lew was run over by a motorcar not far from their apartment and died. It is unclear whether this was a preconceived murder or not. Zavrel summed things up as follows: “We have lost the most unique salon, one of the central points of international culture.”

Wanda returned to Paris in 1920 and moved into an apartment in the 18. arrondissement. Here Rilke was also one of her guests. She resumed composing and giving recitals, gave lectures at the Sorbonne and master classes at the École normale de musique. In 1921 she undertook a concert tour of Spain, during which she played with Pablo Casals and met Federico García Lorca, Manuel de Falla and Andrès Segovia. In 1923 and 1924 she toured through the USA twice. And in the following year she moved into a house in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt, north of Paris. Two years later she had a concert auditorium built onto the house, which was also large enough to accommodate her constantly growing collection of historical instruments and her library. Here she also gave masterclasses until 1939.

Landowska gave her last recital in Germany in 1930 with the Berlin Radio Orchestra in the Singing Academy there. From 1933 onwards she was defamed as a “Polish Jew” and “nauseating agitator against the new Germany”, who was “also suspected of spying against Germany”.[8] In 1938 an article by Brückner-Rock appeared in a national socialist lexicon of “Jewishness and Music with an ABC of Jewish and non-Aryan Music Enthusiasts”.[9] In the same year she took up French nationality. After German troops invaded France she fled to Banyuls-sur-Mer in the south of France on 10th June 1940, where she lived with her friend the sculptor Aristide Maillol. In September German musicologists from the “Sonderstab Musik” – it was part of the “Einsatzstab Reichleiter Rosenberg (ERR)”, a Nazi organisation specialising in looting cultural goods in the occupied countries – plundered her belongings in Saint-Leu-la-Forêt and confiscated her collection of instruments and her library consisting of 10,000 copies of sheet music, handwritten compositions and books, along with her paintings and valuable antiques to Berlin. (ill. ) In 1941 Landowska gave her last European recitals in Geneva and Lucerne. Thanks to the help of the Emergency Rescue Committee in Marseilles she emigrated from Lisbon to the USA on 29th November.

Landowska settled in New York where she resumed her masterclasses. In 1942 she gave her first recital with Bach’s Goldberg Variations in the New York City Hall. In 1950 she moved to Lakeville, Connecticut where, until 1954, she concentrated on recording the whole of Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier”. She died on 16th August 1959. Her urn was laid in the cemetery of Taverny, near Saint-Leu-la-Forêt. Some of the particularly important historic instruments which had been confiscated were brought from Berlin to South Germany in May 1943, and kept in Raitenhaslach monastery near Burghausen am Inn until 1945. In September 1945 the US army discovered the store of stolen art and took the instruments in the Landowska collection to the Central Art Collecting Point in Munich. From there they were transported to Paris in July 1946 and handed back to the French Commission de Recuperation Artistique following an official request.[10] In the decades after the Second World War other instruments came to light at international auctions. Landowska never received any compensation from the Federal Republic of Germany.

Axel Feuß, December 2015

Further reading:

Anonymous: Ein Konzert auf alten Tasteninstrumenten im Musikhistorischen Museum in Köln a. Rh., in: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenbau, vol. 31, Leipzig 1910/11, p. 723, 725

Alfred Heuß: Das kleine Bachfest in Eisenach, in: Zeitschrift der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft, 13, Leipzig 1911/12, p. 27-29

Arnold Schering: Das VI. deutsche Bachfest in Breslau, in: Zeitschrift der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft , 13, Leipzig 1911/12, pp. 365-368

Lotte Zavrel: Wanda Landowska in Berlin, in: Das Unterhaltungsblatt der Vossischen Zeitung, Nr. 17, Berlin, 20.1.1928

Ingeborg Harer: Landowska, Wanda, in: Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG), ed. Ludwig Finscher, Personenteil 10, Kassel u.a., 2. edition, 2003

Martin Elste: Die Dame mit dem Cembalo. Wanda Landowska und die Alte Musik. Catalogue of the special exhibition in the Berlin Museum of Musical Instruments, Berlin 2009

Martin Elste (ed.): Die Dame mit dem Cembalo. Wanda Landowska und die Alte Musik, Mainz 2010 (with a discography of original recordings with Wanda Landowska)

![„Erinnerungen an Wanda Landowska” [‘Memories of Wanda Landowska’] „Erinnerungen an Wanda Landowska” [‘Memories of Wanda Landowska’] - Poster for the exhibition in the Bachhaus Eisenach, 05/01-11/13/2011.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/plakat_bachhaus_eisenach_2011.jpg?itok=76h6jPXt)